Our Verdict

The tactical mech game we've been waiting for. On and off the battlefield, every decision in BattleTech is meaningful.

BattleTech, as you might expect, is a game about massive mechs stomping around a battlefield, throwing ordnance at one another. But, less obviously, it’s also a game about a small business owner plugging away in an uncaring galaxy, staying one step ahead of payroll, and doing anything they can to keep their spaceship flying.

It’s a brilliant combination.

The BattleTech board game has been around for decades but this is the first videogame that can be considered a true adaptation. Previous games, like MechCommander, have approximated parts of the ruleset, while others, such as MechWarrior and MechAssault, have been spin-offs set in the same universe.

What Harebrained Schemes have achieved, however, is to capture the nuances and unique flavour of the original BattleTech. It brings in weight-class initiative-dictated movement phases, stability stats, and Called Shots. It’s very exciting for people who, like me, enjoy stats, but those that don’t can get away with just knowing the game is richer for it.

On the battlefield, you command a lance of up to four pilots, each in the cockpit of a giant war machine called a BattleMech. These towering walking tanks are composed of a vulnerable inner structure that bristles with weapon systems wrapped in a thick layer of armour. When you meet the enemy’s units and begin launching shells, missiles, and laser beams at each other that armour peels away, exposing the core – and eventually the pilot – to attack. Arms will be blasted off, ammo cages will explode, and mechs will overheat. It makes for an excellent turn-based tactical game.

Informing that core are a number of simple systems that combine to create a complex web of tactical considerations. Take heat-management, which makes you carefully choose which weapons to fire each turn – the fear being that you’ll overheat one of your mechs, which forces it to shutdown and cool off, leaving it vulnerable to attack. Stability is another that can dismantle your front if left unattended: if a mech is pummeled with enough ballistic fire it will teeter and potentially topple to the ground, injuring the pilot inside and leaving them exposed to targeted assaults until they can stand back up. Then there’s line of sight and sensors, which make scouting with a spotter mech an essential strategy, allowing you to rain fire upon your enemy without them even seeing you.

Success isn’t only down to what you take to the battlefield. The battlefield itself, and how you utilise it, plays a huge part. There are advantages to be gained from firing down on an enemy from a high position, cover bonuses to hiding your mechs in thick forest, heat dissipation bonuses to standing a mech in deep water. You have to read the map to make the best use of your lance.

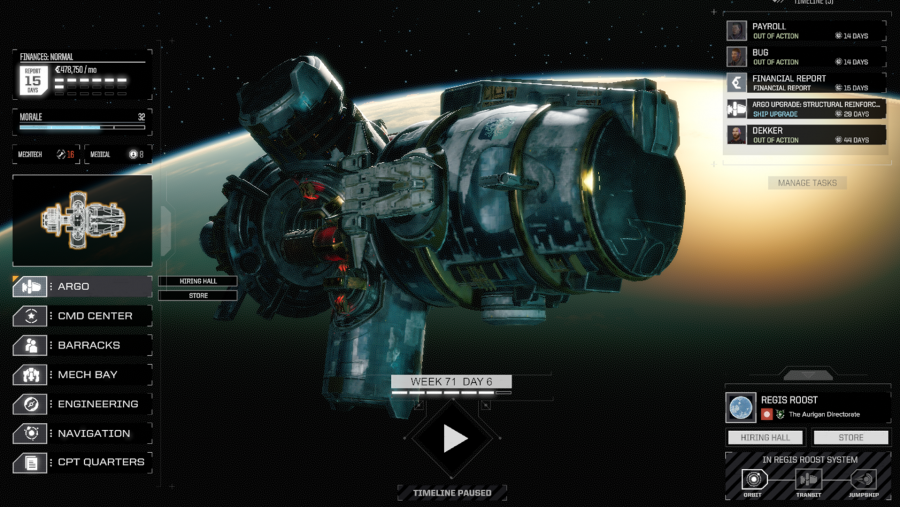

All of this articulated-metal-foot-on-the-ground action is tied together by a persistent management layer that makes BattleTech radically different from its extended family of games. You are the manager of a mercenary outfit, the pilots are your employees, and the mechs are your assets. You have to pay for them every month – either in salary or maintenance costs – or face desertion You gain the necessary capital by taking on contracts from clients throughout the galaxy: protect a convoy here, destroy a lance of mechs there. Each job nets you cash and salvage that lets you keep flying and expand your operations.

As you progress through BattleTech’s story – which follows a deposed queen fighting to take back her small Fiefdom in a wider galactic war – you gain access to a sprawling ship that can be upgraded with morale-boosting facilities for your pilots, a larger mechbay so you can store more mechs, and more med bays to care for the inevitable wounded. This management layer isn’t a tacked on extra, it’s what drives you to your most exciting battles, and your worst decisions.

Any damage done to your mechs or pilots takes time to heal. It’s common, particularly BattleTech’s early game, to finish a job with most of your pilots in the medbay and your mechs in the shop for repairs. They can be there for weeks – I had one pilot out of action for nearly three months after their mech got cored by a PPC on a particularly gruelling job. But, when I didn’t have enough money in the bank to meet payroll, I’d have to take on jobs anyway.

This is where BattleTech shines, it’s not about completing missions on your best day, it’s about playing as best you can on your worst. I took light mechs to fight heavy mechs, half lances to fight full lances, I put rookie pilots into my most expensive machines. Anything to keep my ship flying.

When you field an ill-fitting lance, the only way to get ahead is to twist the rules of BattleTech to your advantage. With the light mechs, I kept them mobile and close to the enemy mechs equipped with powerful long-range weapons. If I moved every turn, positioned my mechs in terrain that provided cover bonuses, and stood in my quarry’s blindspot, I could eke ahead. It was also vital that I kept shooting the same side of the enemy, repeatedly scraping away at the same outer armour, exposing the innards faster than if I took a more general approach.

I still lost a lot of pilots. I mean, I was playing tactically, but it was akin to a plastic fork attacking a machine gun emplacement. What’s important is that I stayed ahead of bankruptcy. I hope the families of my dead digital desperados can take some solace in that.

The material cost of pushing for a win has started making me play in a way I’ve never played in other games – quitting while I’m ahead. There are two tools at your disposal on the battlefield that allow for this: ejections and withdrawals. You can tell a mech pilot to hit the eject button on their turn. The head of their machine will pop off and they’ll launch to safety. At the end of the battle you salvage their mech and collect the pilot. Besides replacing the head, there is no penalty to this action – except having one less mech on the field. Withdrawals are separated into good-faith and bad-faith withdrawals. If you complete your objective or destroy at least one enemy mech then you can extract from a mission with your reputation intact, even get a bit of cash off the client. If you leave before that then it’s classed as a bad-faith withdrawal and your rep takes a hit.

Using these tools in tandem makes a win on the battlefield more flexible. My lance of cobbled-together mechs, and pilots selected based on their ability to leave the med bay, aren’t always going to be able to destroy every mech they face, no matter how tactically I play. But I can focus, instead, on just taking down one or two enemy mechs, pushing to complete an objective and calling in the dropship when enemy reinforcements arrive. I get paid, my reputation remains intact, and my mechs and pilots live to fight another day.

The persistence between contracts justifies the decision to quit the battlefield. It can feel really good, like you’ve snatched victory away from your enemies. When one of your mechs is surrounded and about to be lit up by a barrage of autocannon fire, it’s deeply satisfying to hit the eject button and watch the pilot launch themselves to safety.

In all the other BattleTech videogames you’re taking factory-fresh mechs into battle, so the stories you play a part in are only those written by the developers. In BattleTech, the persistence between battles lets you weave a whole new plot through the game, one filled with characters and stakes that are wholly your own. There’s the pilot who, no matter what mech you put them in, always ends up in the hospital after a mission, the plucky Locust that, even when you’re fighting towering Assault class mechs, manages to dodge their waves of fire, and the stumpy-legged Hunchback who is always running behind the pack, trying to keep up with its friends.

The emergent story is only possible because Harebrained Schemes have done such a good job of tying together all of BattleTech’s systems – on and off the battlefield – and then applying pressure to them all simultaneously with the weight of your monthly outgoings. It’s a delightful struggle to play against, as every month you squeeze together enough credits to make payroll feels just as good as slamming the eject button on a mech surrounded by enemies – a desperate victory against all odds.