Sometimes it isn’t just the game you’re playing, it’s all the surrounding factors that determine how and why you’re playing the game at that exact moment. The idea that external factors might affect enjoyment levels isn’t something people often concede in game criticism, nor in pub arguments, because if you admit it that judging one game against another is anything other than a scientific process, the whole house of cards falls down. Personally, every time I think about Half-Life, the greatest game I have ever and will ever play, I see that house of cards levelled in front of me.

Is it even possible to determine the best PC games of 2015? Yes it is, there they are look.

Here’s the problem. Prior to Christmas 1998, the only gaming experiences I had came either from the 2.6-inch, 2-bit screen of a Nintendo Game Boy, or from sitting cross-legged and waiting for my turn on the SNES at friends’ houses. Sophisticated game design to me at that point looked like The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening.

So on Christmas Day 1998 when my parents bought me a home computer and a copy of Half-Life, everything changed. Just like that, I’d gone from peering at varying shades of green on a chirpy handheld to playing what’s widely considered one of the best games ever made, on a machine whose capabilities at the time to me seemed almost magical. It was an absolutely perfect set of circumstances.

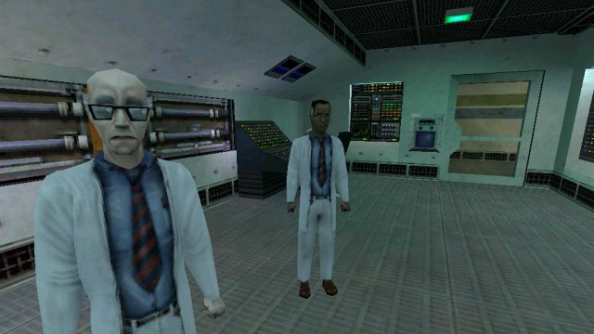

The very thought of the opening train ride gives me shivers. With every new sight – an enormous vault door opening, a mechanised machine loading mysterious samples, the enigmatic G-Man strolling by – my twelve-year-old mind was increasingly blown.

I also remember being incredibly excited to discover that the drinks machines actually dispensed cans, and that if you hit ‘E’ on a microwave in the kitchen you end up frazzling some poor research scientist’s breakfast, much to his consternation. This kind of detail and interaction was a new dimension entirely.

I was terrible at it, of course. I’d been somewhat cavalier in my decision to embark on my first ever first-person shooter, using mouse and keyboard controls for the first time, on ‘normal’ difficulty, and as a result every single enemy in the game had at least a 50% chance of killing me. I didn’t care. Inching through Black Mesa at a snail’s pace, repeating almost every corridor, only gave me more chance to appreciate each detail. I didn’t get frustrated because I didn’t know you weren’t supposed to die this much. (It took me over a week to beat the Tentacle Beast.)

Half-Life feels more like a place I went to than a game I played. I’ve read – and written – a lot about its genre-redefining set-pieces and unnervingly intelligent AI enemies, its puzzles and pacing, the sound and level design, the weapon feedback, and countless other qualities Valve weaved into their debut title. But that’s all just dancing around the real heart of the matter. The fact is, it did a better job of immersing me within its world than anything else ever has.

And, of course, better than any subsequent games ever will.

In many ways it’s great to be able to hold a game up with such holy reverence, and I feel lucky to have experienced Half-Life under such especially intoxicating conditions. But in other ways it’s been problematic. It’s been a bit like losing one’s virginity to Aphrodite and Venus while the Beatles play a gentle live set in the background: where do you go from there?

Naturally, where you go from there is trying to top that high. I’ve spent a large portion of my adolescent and adult life trying to rekindle the excitement of Christmas 1998, walking the halls of Black Mesa in utter amazement. And naturally, I haven’t found it. Not in Half-Life 2, regarded by some as the better of the pair. Not in Deus Ex, or System Shock, or Doom, or Quake. Not in Bioshock, S.T.A.L.K.E.R., Call of Duty, Halo, Dishonored, and not even in Clive Barker’s Jericho.

I keep a healthy detachment to Half-Life 3 speculation and anticipation these days. Because I’ve had to admit to myself that if and when that game ever materialises, in whatever form it takes, I will not enjoy it as much as Half-Life. It won’t make me 12 years old, and it won’t represent a leap forward in visual and audio fidelity equivalent to my Game Boy to PC quantum leap.

That presents a problem in game criticism. Everyone has their Half-Life. Some perfect experience, usually from childhood, by which they judge all videogames. And any comparison made by that metric is hugely flawed, obviously. You try to take external factors out of critiquing, but you’re only human. A human who’ll never let a game up onto Half-Life’s pedestal, when it comes down to it.

Thomas Wolfe said you can’t go home again. It’s highly impractical advice to anyone with a permanent address, but it’s especially pertinent to this topic, because what he’s really saying is this: Half-Life probably plays like a load of old bollocks today. Don’t go back and play it again, because the yardstick by which you judge all other games will crumble when you do, and from that point on you’re doomed to an endless purgatory of staring impassively at your Steam library with no more desire to play one game than any other because the concept of quality is a lie. Thus, you play none.

Cheers for that, Valve.