I wasn’t expecting to laugh. Valiant Hearts is set in the thick of First World War, so, as you can imagine, the subject matter is often bleak. You’ll perform battlefield amputations, become a prisoner of war, and be one of the first soldiers to be attacked with mustard gas. But, despite this, I did laugh.

Incredibly, Ubisoft have managed to create moments of unexpected joy within a very dark game. All without stepping away from the brutal reality of the conflict.

You start Valiant Hearts in a recruitment line, controlling Emile, a farmer from the south of France. Emile joins the army in the first days of the war. By holding right you run him down the line, through the medical assessment, through the changing room, and out into basic training – a sly nod to the open doors recruitment policy active in 1914.

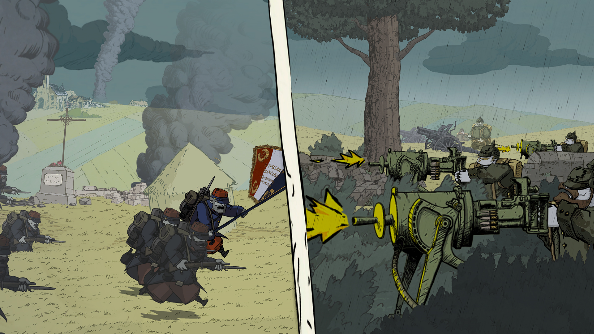

Ubisoft have filled Valiant Hearts with these little touches that hint at the society which defined the conflict, whether it’s the treatment of young men as cannon fodder, the simple tactics of men commanding the troops, or institutional racism. For instance, the first time you meet Freddie he’s being assaulted by a group of white soldiers. It’s Emile’s job to help him out.

The fight’s taking place next to a steam engine at the front of the train, right beside the steam exhausts. By yanking on a conveniently placed chain you’ll vent steam at some of the soldiers, driving them away. There are some left behind, though, and the chain controlling the exhaust aimed at them is out of reach on top of the train. To get to it you have to find a bottle of wine to bribe a guard, conduct an army band to start playing a tune to distract the guards, climb onto the train and leap between the carriages to reach the front and the chain.

Valiant Hearts is a very easy puzzle game. It’s clearly been designed for accessibility. You can only over carry one item so the puzzles are never too complex. Plus, there’s no speech in the game, at least, no dialogue. Instead, characters use pictograms to communicate, tying into the game’s comic book art style. At one point, after Emile’s become a prisoner of war, you’re ordered about by your captors, told to prepare food in the kitchen or fetch water for their dog. All of it’s done through these simple cartoon messages.

Ubisoft have been clever with what the messages contain, too. At one point Freddie, who along with Emile is one of the five characters you control in Valiant Hearts, comes across a Gurkha laying dynamite. The two share no language so the pictograms are the hand signals the Ghurka is making, not simply pictures of what he is wanting.

However, that simplicity can become problematic. When control switches to Anna, a Parisian veterinarian who goes to the front line to become a medic, you’ll be healing soldiers wounds by playing a rhythm game. The track bar is a dirty bandage and you hit A when your cursor lines up with the beat. When you’re in the trenches, sawing through someone’s leg before it goes septic it feels inappropriate to be playing a rhythm game, it detracts from what you’re doing.

That was the only point in my time with Valiant Hearts where Ubisoft seemed to lose control of the tone it had otherwise nailed.

What underlies everything in Valiant Hearts, from its comic-book art style, to its caricatured characters, to its emotional story is Ubisoft’s confidence. They’re not afraid to experiment with what a player will accept in a World War One game. For instance, you pick up control of Anna in Paris on the night that all the city’s taxis are ordered to carry soldiers to the front line. After you’ve managed to repair your own taxi you launch into a mini game that sees you driving to Belgium in a taxi loaded with excited soldiers while dodging traffic to the Can-Can.

It was moments like that which left me enraptured with Valiant Hearts. I’m desperate to see how the rest of the game plays.