Hearts of Iron IV is Paradox’s long-awaited grand strategy wargame hybrid, simulating World War II and creating a multitude of compelling what-if scenarios. What if Italy tried to recreate the Roman Empire, creating a second fascist faction? What if France was torn apart by communism before the Germans marched across the Rhineland? The war is inevitable, but what it looks like and how it plays out changes from game to game.

For more war, take a look at our list of the best strategy games on PC.

It’s a great premise and is blessed with a bounty of complex systems waiting for an armchair general to oversee. It’s exactly the sort of massive, multi-layered strategy game that Paradox Development Studio is known for. But I’ve struggled to love it like Crusader Kings II or Europa Universalis IV, and I’ve had to fight the game just as often as I’ve had to fight wars. Struggled, but not entirely failed.

Here’s the setup: you can choose between two scenarios and any nation on the map. The 1936 start offers up the most freedom since the main course isn’t likely to begin until 1939, so you have plenty of time to build your nation’s infrastructure and economy, work through the gargantuan research trees and, if you want, attempt to subvert history. The 1939 start is more historical, and puts the focus on war rather than diplomacy or nation management.

Now, while you have your pick of nations, the game favours the big players like France, Germany, the USSR, Italy and the like. If you choose to play as Argentina, for example, you’ll be playing with a more generic deck, essentially. Tech and national focuses – more on them later – aren’t as bespoke, and there simply aren’t as many opportunities to exert your influence over the world. There are exceptions, like Poland, which is sandwiched between two aggressive superpowers like a nervous slice of smoked meat, but generally the most fun is had commanding a more prominent nation.

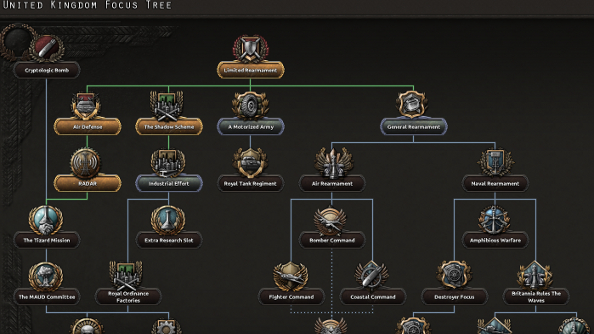

World War II is coming whether you like it or not, but there’s a lot to do before it begins. Each of the main nations have historical objectives and things you’re going to want to do if you expect to survive the first year of the war, but there are even more alternative routes to power.

Take Italy, for instance. I decided to shun the Reich and the Axis and create my own faction, with Franco’s Spain and a now fascist Greece. We ended up in the war, as I really wanted to take out France, but we were a separate entity, fighting alongside but not quite with the Axis. When Germany fell to the Soviets, Italy became the only thing standing between communism and the rest of Europe.

While I guided Italy through these events, they were really inspired by the country’s various national focuses. You select them from multiple trees, and they represent both the historical and potential routes the nation could go down. So you can work your way down a tree that represents what actually happened, like Italy developing North Africa and eventually teaming up with the Reich, or you can choose alternatives that lead to entirely different situations.

These focuses confer bonuses, like increased research speed for air support and tanks, or even thrust an ultimatum upon another nation. As Germany, for instance, you can demand Danzig from Poland, and the Poles might even concede that territory. They might not, however, and that means war. Indeed, that event tends to lead directly to World War II. But it might not! There’s no dearth of surprises. You could find yourself, as the Reich, crossing the Maginot Line in 1936 after the UK and France declare war in response to the remilitarisation of the Rhineland, kickstarting the war early, with nobody really prepared for it.

If, in the likely situation that a global war doesn’t kick off until ‘39, however, then you’ve got three years to meddle with the world. Your goals change depending on your chosen country, of course. The Germans need to build their industry back up after the Great War, the USSR have to go through the terrors of Stalinism and nationwide paranoia, where high level military officials and politicians become victims of Stalin’s fear of traitors, and the USA needs to fix itself after the Great Depression.

The diversity is undeniably impressive. A campaign as the USSR is nothing like a UK campaign, and indeed a second USSR campaign is also just as likely to be incredibly different from the first. Maybe you make a deal with the fascists and work together against the Allies. Perhaps you ignore the west altogether and give China and Japan all your attention.

Making those big picture decisions is empowering stuff, with tweaks to history having a dramatic impact on how events play out. Start supporting communists in France, which can be done with a simple click and a small amount of political power and you can change the landscape of 1940s Europe drastically. Political power, it should be noted, is a resource generated over time and through some of the national focuses that allows players to exert their will internationally, through diplomacy, and domestically, by employing new generals, political theorists and industrialists.

The problem is that once you’ve committed yourself to a series of national focuses and figured out what technologies you’re interested in researching, there’s a lot of waiting to do.

At the start of a game, there are all these problems and issues vying for your attention. Should you build some oil refineries to support the production chain of tanks you’ve just set up? Do you need more military factories so you can churn out more of the parts, supplies and machines that are needed to build up your armies? Should you focus on civilian factories first, since the more of them that you have, the quicker you’ll be able to construct railways to get your troops moving faster, anti-air to protect your factories and more dockyards for your ships?

Once you’ve got that out of the way, that’s when the game starts to slow down. Potentially. There might be a lot of things happening under the hood, but that just leaves you to wait for stuff to be researched or built. In the meantime, there’s surprisingly little to do. That is, unless you’re willing to start throwing your weight around early, and get yourself into some pre-WWII conflicts.

See, it’s war, not surprisingly, that Hearts of Iron does best. If you want an example of a game that manages to find a perfect balance between micro and macro, then Hearts of Iron is it. As long as you’ve concerned yourself with production lines and resources, you can ensure that – if you’ve got the manpower – troops, planes, ships and supplies will continue to be generated, allowing you to get on with the important business of fighting wars. Any divisions that you field can be grouped together in armies, and then given field marshals or generals – each with experience levels and special talents – who give them bonuses. Once you’ve sorted out your armies, it’s time to manage the fronts and develop battle plans.

Battle plans! This is really where Hearts of Iron feels a bit special. When you’ve got an army selected, you can draw up a front across a border, and that’ll send your troops to that imaginary line, where they’ll dig in. You can build some land forts for extra defense if you want, too. Once that’s done, you’ll then be able to paint several new lines. An offensive line denotes where they’ll march to, and you can also mark out a fall back line, so at the click of a button all your units will tactically retreat to a specific place.

When you activate a battle plan, your armies will move automatically, and even reinforce areas where your line is at its weakest. There’s a singular joy in watching your forces pushing into enemy territory, taking it over in real-time, changing the colour of the massive map and rearranging its borders.

There’s a lot of flexibility too. Winning a war is all about forcing an enemy to capitulate, and you do that mostly by taking key areas. How much territory you need to take depends on the national unity of the nation, so the more troubled the country is, the less effort is required to conquer it. So it’s sometimes worth making a battle plan that gets your troops to rush toward specific cities, ending the war as quickly as possible. And you can tweak the plan so that divisions take better routes, perhaps avoiding mountains and river crossings, for example.

If you prefer micromanaging your army, that’s perfectly viable as well. Individual divisions can be selected and directed to help different parts of the line or flung toward important objectives. And there are big benefits to micromanagement, as even a small number of tightly controlled units can make the difference between victory or defeat. This is never clearer than when you send a small number of volunteers to help out in other wars. In the Spanish Civil War, for example, I’ve never seen the Nationalists win without the help of my tiny group of volunteers.

So, if war’s so great, why not be at war all the bloody time? Global tension is the reason. Every aggressive move you make increases global tension, and the higher it gets, the closer the planet is to World War, putting a halt on other plans. The impact of global tension is a wee bit different depending on your chosen country, however. Nations like the UK can’t do much at the start, because their citizens are very much against war. So the higher global tension is, the more that the UK can do. If you’re a fascist or communist nation, however, you don’t want the UK and chums interfering. You want to hold off on the war for as long as possible, so you can start it from a position of strength. You can only get there, of course, by – you’ve guessed it – making decisions that will raise tension.

On paper, it both simulates the actual tension of the time and forces aggressive players to think long and hard about what bold moves they want to make. But it can also be a giant pain, especially if you’re playing as a democratic nation. Indeed, I quickly tired of playing those countries, because of constantly being told I can’t do things due to some arbitrary percentage. I can’t act, because my soon-to-be-enemies haven’t been aggressive enough, and there’s bugger all I can do about it.

Unless you’re playing as an expansive power like the Reich, Italy or the USSR, you’re going to be spending most of the first three years of the gaming focused on internal stuff. You’re not going to be flexing your muscles or changing the world; you’re going to be waiting for World War II to kick off. And even if you are playing a historical aggressor, there are still big limitations imposed before the war.

Factions, Hearts of Iron’s alliances, suffer a great deal because of this. AI countries seem to predisposed toward not making alliances with anyone. You might have the same political ideology, the same potential enemies and similar goals, but they simply won’t join you because you’re not at war. And it’s not just any war, either.

As Italy, I kept trying to buddy up with the Spanish, who I helped during their Civil War, but the tooltip kept telling me that they wouldn’t team up with me because we weren’t in a war. Ok, I thought, I’ll wait till I’m at war, and I did. But no, then they wouldn’t join me because they didn’t want to get embroiled in my war. So what the hell is the problem? It’s that, generally, nations don’t unite until the last possible second, right when World War II begins. And even then, they’re just providing bodies.

It’s weird that so much effort has gone into creating this brilliant battle plan system, and yet it completely falls apart when you introduce an ally. They just do their own thing, which frequently involves taking zero risks and spending most of their time entrenched, as if they were just fighting a defensive war. And there’s no way to communicate with them beyond the bog-standard diplomacy, so no way to work with them and execute battle plans with them in mind. You’ve got to guess what they are going to do.

You get used to it, certainly, and generally the AI sort of follows your lead. If you’re both entrenched along a border and you decide to push toward your offensive line, there’s a good chance that they’ll follow suit and help you smash through the enemy defenses. But that lack of control and the absence of information about your allies’ plans is a bizarre omission.

To put it in perspective, this is a game that simulates 1936 and onward by the hour, where you are in charge of a nation’s infrastructure, customising divisions by adding new units like artillery or new types of tanks, and giving commands to air wings so you can specify targets like enemy buildings or ground units, yet you can’t tell your ally to focus on getting to Berlin.

Despite this, when World War II kicks off, it’s a sight to behold and – usually – a delight to manage. I remember, years ago, leaving an open can of Coke on my desk, near an open window. When I came back, I was faced with a horde of ants running from the window to the can, covering everything in their path. That’s what the world looks like when the big war kicks off. But with air support and guns and risky marches across the Alps.

It’s so big that commanding it, at first, seems like it might be a nightmare. Sometimes it is. There’s a hell of a lot of clicking and faffing and I still think that I’ve got a lot to learn about managing my air force, and God knows that the game does a terrible job of explaining its complexities. The tutorial merely offers hints and spurts of guidance in regards to only a few aspects, barely teaching you at all, and while there are a lot of tooltips, they aren’t always clear, and sometimes they are straight up wrong.

The UI does make things a bit easier, however, and when you get over the initial hump, where everything is gibberish, it starts to become a great deal of fun, managing a conflict that’s spread across the globe. You can designate theatres, for instance, and customise your forces for specific regions. And with a double-click, you can switch between the Western Front to your newly-created East African Front, so that you’re in complete control of forces separated by oceans and continents.

At the heart of game’s problems is that it often feels like two games that don’t always sit next to each other comfortably. 1936-1939 is mostly a grand strategy game, but one with severe limitations and covering a very short period of time. 1939 onward is a wargame, where all the meat is, where everything is subservient to the game’s ginormous clashes. And while the first half gives you, on the surface, the opportunity to really mess around with history, mostly – if you’re not playing aggressively – you’re going to be waiting about for interesting things to happen.

Compare this to Paradox’s last two hybrids, Stellaris and Crusader Kings 2, and Hearts of Iron IV comes up short. CK2’s roleplaying elements weren’t separate, they were fully integrated into the grand strategy game, and Stellaris’ 4X stuff was merged with the grand strategy part in such a way that you couldn’t see the seams. Hearts of Iron, on the other hand, feels like two games forced together. When it works, it’s brilliant, and the most ambitious simulation of World War II that I’ve played. But more often, I feel like I’m in a waiting room, reading a magazine that – while interesting – isn’t what I’m really here for.

Right, ok, I could have ended the review right there. I’ve even got a rubbish analogy about sitting around in a waiting room. Job done. But here’s my dilemma: I bloody love Hearts of Iron IV. Even when I’m not doing anything, I really am, because my brain is still racing through all the things I need to do, all the focuses I’m contemplating, all the countries that might soon face my wrath. Also, I’m a man who genuinely enjoys watching progression bars slowly move, letting me know how long I have to wait for a factory to get finished. I live for this stuff. Do you? Then you’ll probably love this. For everyone else, there’s a number below.