Editor’s note: this post was original published during Oculus Rift’s launch week back in March 2016. We’re reposting it one year on to see how the predictions hold up. What do you think?

Great. The first Oculus Rift consumer model pre-orders arrived at the doorsteps of their excited and devoted recipients on 28th March, and the very next day here’s some internet schmo with a hot take on why those people are all wrong and wasted their money. Where do I get off, right?

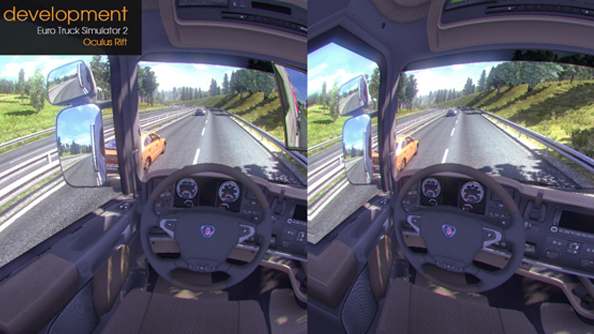

Here’s the thing, though: I get it. I used to be excited about VR, too. I’ve sought out strange and inventive new experiences from across the internet to test out on my Oculus Rift DK2. I’ve tinkered with third-party software and .ini files to patch in quasi-support for old games, in the name of curiosity. I climbed Everest, toured virtual real estate and broke Aperture Science property thanks to the Vive. I swam with sharks and hacked apart suits of armour with PlayStation VR. I used to be all about virtual reality.

Until I spent a lot of time with it.

After a while, I started wondering why all the VR coverage I was reading – and crikey there’s been a lot of VR coverage in the last year, hasn’t there? – was so unilaterally positive. Why none of it seemed to chime with my own experiences of it.

Not having a word of it? Fine, check out the best VR games on PC instead. See if I care.

Yes, it feels great the first time you put on the headset and realise that the virtual space encompasses you. It’s exciting and immersive. But what about the motion sickness, the discomfort, the constant tech issues, the sense of its novelty wearing off, the sky-high investment cost, the problem with traditional WASD controls becoming suddenly disorienting, and how counter-intuitive it is after years of gaming on a screen to have to physically turn 180 degrees to look behind you? Some of those issues are a by-product of pre-consumer hardware. Many of them aren’t.

The probable reality is that VR coverage has been so overwhelmingly positive because there’s potential in it to become a burgeoning new sub-sector, with a lot of money to be made. Facebook, HTC, Valve, Samsung and others all have deeply vested interests in the platform’s success, and their combined PR muscle has impact on a truly global scale. Media outlets see an opportunity to be ‘the place for VR.’ Independent game developers and small studios see an opportunity to get in on the ground floor and make a name for themselves. Over the past year, those three forces have combined to create a surge of positive publicity for VR.

And that’s fine, but it’s time the dissenting voices also made themselves heard. So here’s an internet schmo with a hot take on how, why, and when VR will fail.

It doesn’t mean much to say “VR will fail” and leave it at that. By what metric? Well, what that statement means to me refers explicitly to gaming. I’ll break it down like this:

How – the user base won’t be big enough to entice major developers

Sales of Oculus Rift and Vive headsets over the next 36 months won’t be sufficient to entice enough game developers and publishers to support them with software. Without system-selling titles, the platform will suffer continued poor headset sales until it’s no longer financially viable for their platform holders to continue supporting them.

Anyone with a stake in OnLive, Ouya, 3D, or uDraw will read that tale of decline with bitter recognition. As will anyone with a stake in VR the last time manufacturers tried to convince us it was the next big thing, in the optimistic early ’90s.

You read about Vive selling 150,000 units in ten minutes as soon as pre-orders went live. You read about Oculus’s site almost going down under the weight of traffic when Rift pre-orders went live. What you haven’t read since then are the subsequent unit sales for each device.

Facebook CFO Dave Wehner has stated that the Oculus Rift’s revenues “won’t be material” to the company’s 2016 financials. When you consider the amount of money passing through Facebook’s accounts, that doesn’t sound like a big deal. But did you hear anyone from Microsoft or Sony talking about their upcoming consoles prior to Xbox One and PS4’s launch in the manner of Wehner’s following quote?

“With Rift, it’s really… you know it’s early in the evolution of VR. It’s early to be talking about large volume, so at this point I don’t think we’re giving a lot of color around supply chain and that sort of thing. It’s not going to be material to our financials this year.”

As RoadToVR point out, Facebook’s 2015 revenues were $17.93 billion. It’s speculative, but reasonable, to say that $1 billion might constitute ‘material.’ At the Rift’s current $599 price tag, that equates to 1.67 million units. It’s worth noting at this point that Facebook bought Oculus for $2 billion in 2014.

Some context for those numbers: Samsung sold “just under” 1.6 million 3D TVs in their first year. More pertinently, the Wii U’s first year sales were 4.3 million units. That was sufficiently low for major publishers Ubisoft and EA to announce that they’d be pulling back their support of the console.

There’s a lot of guesswork involved in making comparisons using those figures. Is developing for VR more costly than developing for Wii U? I’d guess so. Is $1 billion the point at which Oculus sales become “material” to Facebook’s revenues? I guess. These figures are also specific to Oculus. Will Vive sell better? I’d be guessing.

But what those figures tell us, inarguably, is this: VR is not too big to fail. Nintendo found a way to keep the Wii U alive with excellent first-party software – Valve have that option, but do they have the inclination to follow suit? If they did, you’d imagine the Vive’s launch lineup would reflect that. And I mean a game, not a tech demo. The tech industry invested billions into 3D, and watched as consumers stubbornly refused to change their lifelong viewing habits. Which, as Rock Paper Shotgun point out in this fantastic piece, is just as pertinent a point in gaming.

The difference, you feel, between previous failed technologies and this wave of VR is that there’s such a sense of hope. Such a collective desire for VR to deliver on our fantasies. And its manufacturers are absolutely playing to that…

Why – the user experience doesn’t justify the outlay, and you don’t know that until you buy one

How much imagery like the above have you seen in the last year or so? People in stylish lofts and roomy living rooms, absolutely lost in their VR experience? I’ve seen a lot of it. And I’m not surprised – it’s absolutely crucial for VR that potential users believe it’s the experience they imagine in their head.

It isn’t. It’s somewhere between your expectations and a disappointment. Not an outright disappointment, just – somewhere in the middle. I’m not talking about one headset in particular. I’ve spent hours with the various models of Oculus Rift, Vive, and PlayStation VR, and while there are differences in comfort, image quality and tracking precision between each one, they’re united in being not quite as good as you’d hope.

You can see the pixels. People don’t tend to mention it, because it feels so amazing at first to move your head around and stare at a virtual world that presents itself from all angles. But that novelty does wear away, and when it does you start to notice things like the grid-like appearance caused by the visible pixels inches from your eyes.

It also might make you sick. This issue’s definitely been minimised as each manufacturer’s headsets have been redesigned, but it hasn’t been eliminated because at least part of the responsibility lies with the game developer. Valve, Oculus, and Sony can do absolutely everything on their end to minimise motion sickness, but if a developer releases a game that you control in first-person using WASD and its frame rate is variable, you’ll feel sick.

Which, in turn, means certain established genres just don’t seem to work in VR, not currently. First-person shooters are largely out. Third-person games need a very bespoke approach. Sports games, such as FIFA or NBA 2K, remain untested. The experiences that seem to thrive on VR headsets are those with a fixed point camera perspective, and it’s going to take time for developers to figure out how to use that to their advantage.

The thing about all the disconcerting peculiarities of VR is that you don’t know about them until you’ve tried it. Now – where, and how, are you going to try it before you buy a headset for $600-$800? I know colleagues in the games industry who have yet to strap on a headset, and that makes me wonder how the millions of consumers whom VR’s manufacturers are hoping to get on board are going to make an informed decision before buying in.

The reality of the prospect most consumers face, then, sounds like this: spend $600-$800 on a piece of technology you haven’t tried, on the basis that it matches your imagined experience of that product. Then spend more money on a PC that’ll run it smoothly, and for the best experience, set it all up in a large, empty room which you’ll need to devote to VR gaming alone. Do this, and you can access bespoke titles such as Lucky’s Tale, TiltBrush, Adr1ft, Project CARS and Defense Grid 2.

Launch titles aren’t always indicative of a platform’s fortunes, but with respect to all those titles, none of them scream “$2000 investment”. The major players – Ubisoft, Activision, EA, Bethesda et al – whose IPS can make or break a platform, have taken a step back from VR to see how the headsets sell before plunging money into development. Which means the headsets won’t sell.

When – a gradual three-year decline

It won’t happen overnight. It won’t even be dead and buried within a year, because it takes longer than that for the momentum generated by the PR people of some of the world’s biggest companies to decelerate. But slowly, over 36 agonising months filled with perma-grin press releases about new platform partners, price cuts, and reports about its hardware being used in places like car showrooms and real estate offices, VR sales will stall.

Based on pre-order sales figures alone, the user base will be large enough to attract developers for the initial twelve months. It won’t capitulate like Ouya. But its ambitions were infinitely farther-reaching than Ouya in the first place.

First year sales won’t, however, be strong enough to entice involvement from major publishers and developers, and so twelve months in the early adopters will still have a diet of tech demos and short-form arcade games with which to use their $1500+ hardware investments. The public feeling towards a technology that promised us the world will begin to sour.

Companies faced with poor performance in the games sector will look elsewhere, to corporate applications, to recover costs. Games will no longer be the focus. Eventually, when enough time has passed that those companies can cease support and development without facing major embarrassment, they’ll do so.

The exception will be Sony, whose PlayStation VR will outsell Oculus and Vive significantly, and will benefit from titles developed by the company’s international array of first-party studios. Outside PlayStation 4, VR lives on only in the bedrooms of the rich enthusiasts.

And a few years, perhaps a decade or two, after that, the cycle will repeat. As this BBC retrospective points out, this isn’t VR’s first time around the block, nor will it be the last. There’ll always be an audience for ‘virtual reality,’ because it’s a suitably abstract concept that we can all interpret it to suit our imaginations. Perhaps it’s a victim of its own nomenclature – a term less evocative and more decriptive might help to manage user expectations. Next time.

Exactly how wrong am I about VR? Where should I shove this article, and how forcibly? Let me know in the comments below.