There’s something oddly comfortable about the weight Cluedo puts on your shoulders. Trapped in a stately home with a killer, a smattering of circumstantial evidence and the responsibility of accusing somebody of murder, it should be anything but. But there’s an Agatha Christie vibe to the conservatory encounters, misused candlesticks and errant vicars – a fiction that frees you from treating it as anything other than genre romp. A relative of the jolly Sunday night murder mystery.

Enjoy the occasional experiment in storytelling? Try one of the best indie games on PC.

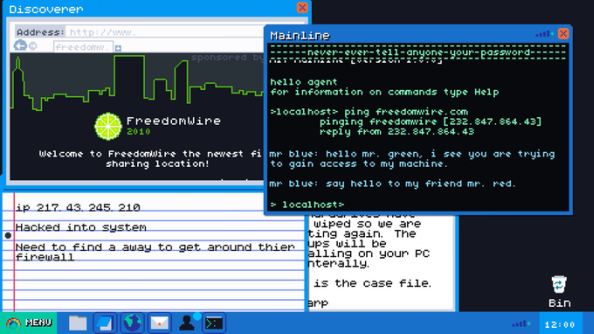

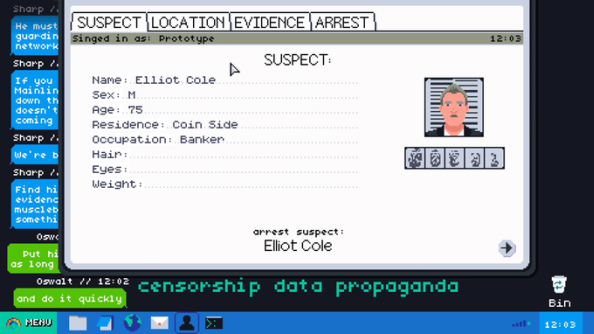

Mainlining asks you to do just the same – collecting evidence and ordering arrests – but pulls the decision-making uncomfortably close. When you double-click its .exe, the game collapses into a Blue Screen of Death, before apparently rebooting into a late ‘90s OS. Before long you’re sat back on the desktop – only it’s not your own, and there’s an email from your superior, demanding you hunt down the hacker who’s wiped MI7’s database.

Even the time in the taskbar matches that of your own PC’s clock. As suspension of disbelief goes, I think I’d feel a little safer suspending a tad more.

“We wanted to remove anything that the player might feel takes them out of the game,” says designer and programmer Sam Read. “I wanted you to feel like you were role-playing this character behind a desktop.”

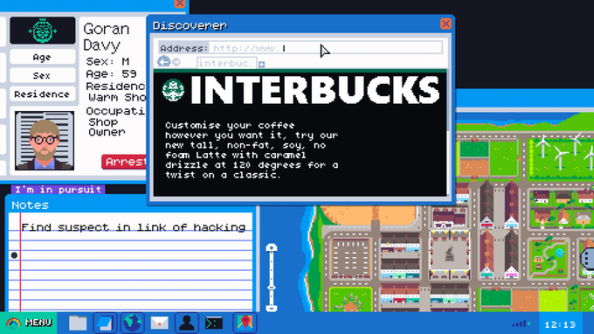

As a newly recruited agent working within the remit of the Blu Pill Act – legislature which has made all online personal data available to the state – your job is to drudge up enough evidence to bring about the arrests of cyber-criminals. You’ll tackle thirteen cases via a series of operating systems and pieces of software as MI7’s systems come back online – navigating command consoles, internet browsers and a pixel artier Google Maps in the pursuit of leads.

In each case you’re looking to secure the longest custodial sentence possible, but methodical completionists might run into trouble. Take too much time and your suspect could catch on; conversely, leap to a conclusion and you might drag your mouse past breadcrumbs linking offenses to more serious internet baddies.

Cluedo was an inspiration, alongside Holmesian detective board game 221b Baker Street. But so, too, were point-and-click adventures. Think of it this way: the desktop is a text-heavy narrative environment that doesn’t require any animated characters or expensive voiceover. My Documents is an ample inventory system. There’s no pixel-hunting and, as a bonus, less backtracking, since you can simply minimise one area of exploration and maximise another.

“The flow and structure of it follows a kind of diamond design – you start off in one place and it lets you explore and go off and discover things on your own,” explains Read. “And then when you’ve got a number of pieces of evidence, it’ll bring you back to a point and deliver some context to what’s going on. And then it’ll let you free again.

“When you’re going through these files, I wanted it to feel like you’re exploring them. Even though you’re not physically moving in the world.”

Mainlining shares with the more unusual adventure games of the ‘90s a sense of uncertainty around the limits of what’s possible.

Players panicked when a policeman stepped onto the train in Jordan Mechner’s The Last Express; that same weightlessness washes over you in Mainlining when, in response to your probing, the crims start hacking back.

Writer Jill Murray, veteran of some of the more progressive Assassin’s Creeds – Liberation, Black Flag and Syndicate – has fun with the medium of text and the duplicity enabled by an anonymous internet. As Mainlining’s plot unfolds, it becomes apparent that certain individuals are going by more than one display name.

Some characters use emoticons, others capital letters and full stops. Some adopt colloquial language, while others indulge in memes. An MI7 receptionist has a fondness for multiple exclamation marks which immediately endears her to you.

“Something I really wanted to convey was the character through the text,” says Read. “So then people could maybe even piece together throughout the game, ‘Oh, these two people speak very similarly, they always have the same sign-off.’”

A real-time conceit means that emails can come in faster, too, when somebody’s panicked or angry. Somehow, the brief space between messages in enough to convince that there’s another person on the other side of the monitor.

For all its quiet benefits, though, the desktop concept has also created some peculiar problems for developers Rebelephant to solve. Where FPS playtesting might reveal habits brought over from BioShock or Counter-Strike, the Mainlining team have to accommodate the expectations players pull from the everyday use of their PC.

“Something that’s been quite interesting has been realising that everyone uses operating systems completely differently,” laughs Read. “I’ve learned a lot about generic Windows from people saying, ‘Why can’t I do this?’. And it’s just that I never knew that feature was there.”

Mainlining has been in full development for just seven months, but prototyping began in the year before that – during which time Read stayed away from similar desktop narratives Her Story and Emily Is Away, in order to avoid leaning on their design solutions.

Occasionally, players will tackle Papers Please-style moral choices – able to put a criminal away for longer, but knowing that evidence has been doctored or falsified. Generally, though, longer sentences are simply harder to bring about.

“If someone had only got a five year sentence, I wanted them to be kicking themselves, because they know on there there’s a longer one and they just need to find it,” expands Read. “It’s that high score thing.”

Working at an agency on the warpath, encouraged (at least initially) to get results regardless of method, there’s a message about privacy and power here for players that want it. Mainlining is impossible to separate out from a world in which scrutiny of organisations like GCHQ is at an all-time high. And over the months, the UK’s Snoopers’ Charter has left its mark on the game.

“In most hacking sims and films, you see the side of the hacker – this rebel fighting against the system,” says Read. “So I wanted to come at it from the other way – you’re in the agency, you see how they run.

“Overall, I guess they’re the good guys. But I wanted to really muddy that up. By the end of the game, I don’t think people will fall on a side. I guess in my mind I’d like them to take a position in the middle, but they might go either way.”