This is the second part in a series looking at pivotal games in the history of PC gaming. Whether due to their scope, amibition, sheer quality or otherwise, these are some of the titles that have defined the medium.

Robert B. Marks is the author of Diablo: Demonsbane, The EverQuest Companion, and Garwulf’s Corner. His newest book, An Odyssey into Video Games and Pop Culture, is coming out on October 15th, and is available for pre-order in print.

“The Citizen Kane of videogames” gets thrown around a lot in the modern ‘games as art’ discussion. And it’s a term that can mean different things, depending on the commentator. Alex Steacy and Cameron Lauder put forward Half-Life as the Citizen Kane of videogames in their Twitch show, Talking Simulator, on the grounds that it had legitimized the medium, just as Citizen Kane had for film. Matt Kamen wrote for Empire that PS4 exclusive The Last of Us “may also prove to be gaming’s Citizen Kane moment – a masterpiece that will be looked back upon favourably for decades.”

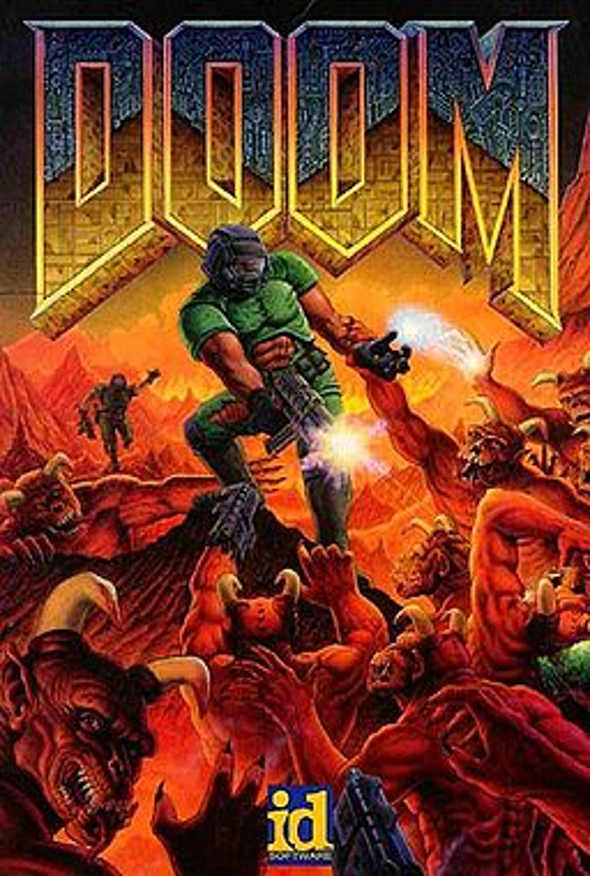

We’re going to take a slightly different tack. If forced to pick a Citizen Kane of videogames (and let’s pretend we are being), we’re going to plump for… Doom. Seriously.

First, let’s rewind. Citizen Kane was a film directed by Orson Welles and released in 1941, based on the life of newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst. While it is a superb film with a powerful story, what made it special was a combination of innovations in cinematography, sound and editing that either took established techniques to the next level or invented brand new ones. As a result, Citizen Kane changed – on a fundamental level – how films were perceived and made. It caused a massive sea change at least as great as, if not greater than, colour film.

And, in the history of the medium, the game with the most similar magnitude of impact – one that forever changed on a fundamental level how we play, make, perceive, and interact with videogame – is, yep, Doom.

Released as shareware in 1993 by id Software, it may seem like an odd choice. In terms of storytelling, it does nothing special – for that matter, it does next to nothing at all. The plot and story do not extend beyond ‘the demons are bad, so go kill them’, and the characters are defined as little more than a guy who shoots demons and the demons who get shot by him. And yet, Doom is a nexus point. Almost every aspect of how we make, play, and interact with videogames today comes from this title.

To understand why this is, context is everything. The computer game world into which Doom was born was divided between commercial game developers such as Sierra On-Line, Origin and MicroProse, and shareware developers such as id Software, Apogee, and Epic MegaGames. There were single-player games and multiplayer games, but rarely, if ever, did the two meet. The internet had not yet reached the public, and those who went online to play games connected instead to BBSes (Bulletin Board Services) and the few massively multiplayer games that had been developed, some of which charged a per-hour fee. Other multiplayer games used a hot-seat approach, or had two players sharing the same keyboard.

By the time Doom – a follow-up and spiritual successor to id Software’s previous titles Wolfenstein 3D (1992) and Catacomb 3-D (1991) – was released, the first-person shooter was already two decades old. The first FPS was Maze War, created in 1973-1974 by Steve Colley, Greg Thomson, and a few others. Maze War was a multiplayer deathmatch game, where players fought each other in a 3D maze. It had flourished during the 1970s in the university environment, and was sophisticated enough to support network play and bots. But Maze War did not make the transition to the personal computer – it did, however, inspire MIDI Maze by Xanth Software F/X, released for the Atari ST in 1987, which is sometimes credited with introducing the deathmatch to the home computer. MIDI Maze, however, was arguably too far ahead of its time and in the wrong market segment. Home computers such as the Atari ST were on their way out, replaced by x86 computers such as the IBM PC and its clones.

The shareware model through which Doom was released is little used today, but for the small independent developers of the 1980s and 1990s it was a way of getting their games into the market without the overhead costs of a commercial release. Doom was divided into three chapters. The first, “Knee-Deep in the Dead,” was released for free on BBSes, and downloaded over modems. It could be copied and shared however anybody wanted. If a player wanted to play the other two parts, however, they had to send a cheque to id Software, who would then mail them the disks containing the rest of the game.

This model turned Doom into a grassroots phenomenon, and contributed in no small way to its impact and success. Everybody could play Doom without spending the $40-60 that a commercial game of similar quality would cost – and playing Doom was a revelation.

It’s hard to describe today. Playing Doom for the first time was to discover what your computer could truly do. Prior to Doom, computer games didn’t tend to make much effort towards visual realism, and most games looked like a cartoon at best. Doom was different.

The levels looked and felt like real places. They weren’t bound by flat floors or right angles. The walls were worn and rusted. This palpable sense of reality came at a time when one of the early pushes for Virtual Reality as a consumer product was occurring, with environments that looked and felt incredibly artificial. Doom was so far ahead of the curve that it left the VR of the 1990s in its dust.

For the computer game industry, it was a turning point. Pushing the graphical envelope in search of visual realism became the rule rather than the exception. In the process, computer games went from avoiding the bleeding edge of technology to living on it. At least as importantly, Doom had been a shareware title – up to that point, shareware was a place for games that were not up to the quality of commercial releases. Doom, on the other hand, demonstrated that shareware developers could hold their own in terms of quality against the larger game development studios. The next year, Doom II was released as a commercial game, making id Software one of the first shareware developers to make a full transition to triple-A development. By doing so, id opened the floodgates – a large percentage of the triple-A game developers producing titles today began as shareware companies who made their transition in id’s wake (and, indeed, as videogames became big business in the early 2000s, it was the former shareware developers who tended to survive the many consolidations).

With a single decision, id Software and Doom also revolutionized how computer games were made: id licensed out the Doom engine. Prior to this, the process of making most computer games began with developing the game engine from scratch. Some engines had been licensed out before – for example, SSI licensed out its Gold Box engine for Dungeons & Dragons games in the late 1980s and early 1990s – but when this happened, it tended to have a franchise model, with the licensee using the engine to make games for the licensor. By licensing out the Doom engine – and later the iterations of the Quake engine – to third-party developers who were not making games for id, the company made it possible for game developers to cut out one of the most time consuming and expensive steps of the process. This model was picked up by others, and it wasn’t long before id had competition, with Epic’s Unreal engine, and most recently the Unity engine, vying for market share among game developers.

All of this was possible because Doom had become its own breakout phenomenon. Built into the game was not only a single-player campaign, but a multiplayer mode that supported both play over the modem as well as computer networks. This type of play had existed in first-person shooters since their advent in the early 1970s, but Doom was the game that brought it to the personal computer, with a vengeance. For months between 1995-1996, the sound of Doom multiplayer games echoing through the halls of University residences was commonplace.

In the wake of Doom, multiplayer became a standard feature in just about any computer game wanting to be taken seriously, and players demanded it: computer games had become a social exercise, one that could take place over a distance so long as both players had a modem. But that wasn’t the only sea change that Doom inspired – on a fundamental level, how players interacted with computer games would never be the same.

id Software’s lead programmer, John Carmack, had been aware that some of the more technically knowledgeable fans of id’s previous game, Wolfenstein 3D, had tried to create modifications and new levels for it. Carmack liked the idea, and built Doom so that the game engine and the levels – known as WAD files (short for “Where’s All the Data”) – were separate entities, easy to access and change. This transformed modding from an activity by a loose collection of hackers into a full-fledged community, sanctioned by the game developer itself, all using Doom as a canvas for their own creative energy. While id didn’t provide its own content development tools, in the wake of Doom a number of triple-A games did, such as Blizzard’s Warcraft II and MicroProse’s Civilization II, and modding became an important part of how videogame fans interacted with the games they loved, as well as a vector for aspiring game developers to enter the videogame industry.

Doom was influential to a degree that no other videogame has achieved, before or since. It changed the way computer games were made and played, how they looked, and even who made them. It rendered all the games that had come before into prologue, and shaped the future of videogaming in its own image. It was so influential that many of the people who argue about the medium’s “Citizen Kane moment” tend to disregard it, unable to remember or even conceive of how different videogames were before a single shareware title named Doom changed it all in 1993.

Told you we were serious.