Editor’s note: this is the final part of a three-part series documenting Romero’s career, spanning his early days as a teenage coder for the RAF, through the id era and up to present day. With thanks to Yorkshire Games Festival.

Since Doom, Romero had become an active producer. In Wisconsin, a tiny fantasy FPS studio named Raven Software had twisted the Wolfenstein 3D engine into ShadowCaster and the Doom engine into Heretic and Hexen. In Illinois, Rogue Entertainment had turned John Carmack’s tech towards arguably the first FPS-RPG, Strife. And in 1996, the year of Quake’s release, Romero was working with developers outside of id on both Final Doom and an extra set of levels for Hexen. The business was successful, but not everyone at id was on board.

Read more: the best FPS games on PC.

“We were doing engine licensing, but we couldn’t do it as well as we needed to because [John] Carmack would always fight against hiring one more person,” Romero recalls. “If we had an engine licensing business we could have one person trying to sell it, and maybe some people making it better all the time. But he didn’t want to do that. Only wanted to focus on game stuff.”

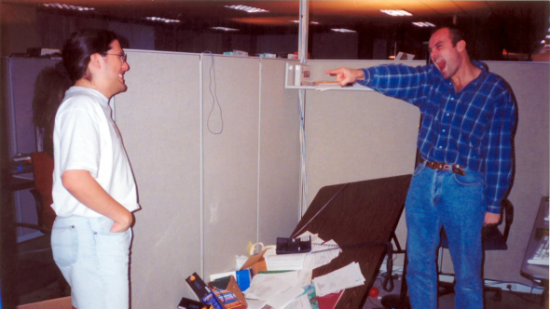

There was another source of friction. Since the days of the Louisiana lakehouse, id had stopped working together in a single room and splashed out on offices. Communication had suffered, and they decided to pool the whole team together in a ‘war room’ for the next game: Quake II.

“I didn’t really have a problem with that,” says Romero. “But it was not a good time, because [John Carmack] was in a bad mood all the time. It took a year to get the Quake engine ready for us to even use, so I’m sure that wasn’t happy times.”

Although Quake had met id fans’ wildest expectations, the first year of its development had seen the design and art teams throw out huge amounts of work as the engine continued to get better.

“The team was burnt out when they actually started making the game,” Romero explains. “It was the hardest game, and it cracked the company in half.”

Even before Quake’s release, Romero was losing faith in the one-two punch of tech and design that had defined his partnership with John Carmack.

“This isn’t what we should be doing,” he told artists Adrian and Kevin Cloud. “I believe this is the last time that we’re going to be able to be leading on tech because the video card manufacturers are going to take it away. We need to innovate and design, it’s the most important thing we can do.”

Romero left id before the year was out. Within six months, half the team that had made Quake had followed suit. One was Jay Wilbur, who went straight into the Unreal engine licensing business at Epic Games.

Romero’s1991 Ferrari Testarossa. John Carmack had a matching one in red.

Romero, industry rock star, was able to form a new studio with Tom Hall in Dallas, funded by Eidos at great expense. He named it Ion Storm, and began work under a new, reactionary slogan: design is law.

“Doom without a good creative team would have been a flop,” he reasoned. “It would have been awful.”

Romero partnered with two passionate developers, Todd Porter and Jerry O’Flaherty, and set up a second studio in Austin under a veteran Origin Systems designer named Warren Spector. But his enduring memory of Ion Storm is of a “huge nightmare”.

Romero found most of his staff on the internet – passionate people with a love for level design and scripting that matched his own. But that turned out to be a mistake. Far from the four developers who built Doom after a decade spent honing their skills, the majority of the team on now-notorious FPS Daikatana had never made a game before.

“Super bad idea,” Romero admits. “If I would have been hiring people who had been in the industry, everything would have been different. Daikatana wouldn’t have come out with all these bugs because it would have actually had industry programmers working on it. So, my bad.”

The game took three years to finish under intense public scrutiny. As original Ion Storm staff left the floundering project, industry veterans were brought in to fill their seats: “Until finally we got to the point where we had replaced them with people who actually knew how to make games.”

“It was a learning process: ‘Don’t do that,’” laughs Romero.

Ion Storm wasn’t quite the unmitigated disaster most remember, however. Tom Hall got to make Anachronox, the great sci-fi JRPG. Warren Spector’s division made Deus Ex, which delivered on Romero’s dream of design as law and spawned a series. And Eidos wound up making money.

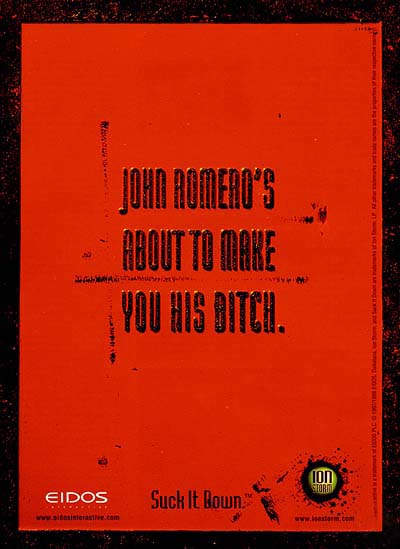

“We ended up being a really good investment, but with a PR nightmare around it,” he eulogises. “There was no Bitch X, Evil Avatar, Something Awful – those didn’t exist until Daikatana’s drama happened, and they all spawned immediately. Everyone on the team was feeding them information.”

The infamous Daikatana ad.

Does Romero wish he’d never released his worst-remembered game?

“Maybe,” he says. “But I made so many games that are far worse than Daikatana.”

Ion Storm Dallas closed down a month after the launch of Anachronox in 2001, and Romero stepped away from FPS design – for the most part embracing smaller teams, mobile platforms and social games over the following decade. In one forgotten and unlikely collaboration, he worked with RPG luminary Josh Sawyer on a reboot of Gauntlet.

But after years of whispers, Romero began working publically on an FPS again this year. Blackroom is to be a heavy metal-soundtracked shooter, art directed by Adrian Carmack. Sold on the promise of weapons that clear rooms, alter the environment and turn enemies against each other, it could not be more Doom if it had the name.

Romero’s ideas about what makes an FPS great haven’t changed with age.

“A really cool shooter comes down to shooting, and having the ability to use skill to do that,” he says. “I’m not a fan of the artificial limitations that games put on you. I like being able to move quickly, within reason – too fast and it’s garbage. That sweet spot of control is really important.”

Romero pours praise on Half-Life 2 for preserving the original’s formula for speed and shooting exactly – and notes that in the new Doom, id did the same.

“I talked to the lead designer, and he basically said they had the original Doom up, and they were replicating the metrics – firing rates, damages, movements and everything,” he says in approval. “So if you were burning down a Baron of Hell in the original Doom, that’s how long it took to burn him down in the new Doom. That was great that they did that.”

Perhaps surprisingly, Romero isn’t so into new Doom’s Mortal Kombat-style glory kills.

“In our games [at id], we never were overly gory,” he recalls. “We easily could have been – we had lots of ideas.”

For Wolfenstein 3D, the team had a nascent plan to show enemies shot below 10% of their health falling to their hands and knees, begging for mercy. But it wasn’t implemented for the finished game.

“You know what? That’s kind of over the line, and also stops progress burning through the level,” says Romero. “It feels mean-spirited, and we’re dark comedy, so we didn’t put too much blood on the screen. That wasn’t the point. Not that I’m saying it’s bad, it’s just that I would have done something different than that.”

If id really were a band in the ‘90s, then their touring line-up has changed almost completely. While Kevin Cloud remains as an executive producer, John Carmack relinquished his role two years ago to become chief technology officer at Oculus VR – where he now works alongside Michael Abrash once more.

The move came as no surprise to Romero.

“John was all about graphics programming,” he explains. “With Quake, we put every dot on the screen ourselves. There was no such thing as a graphics adapter that did 3D.”

Once graphics cards came to define what went up on the screen, however, the magic was out of Carmack’s hands – at least as Romero sees it.

“John was still working with the video card manufacturers to come up with [Doom 3’s] stencil shadowing and all kinds of features that would be really cool to get on the card,” he expands. “He was pushing them, but they have their own plans for what they want to do now. The megatexturing in Rage was a perfect example of, ‘I need to do something else, because I can’t touch anything on the card.’”

Unfortunately, Carmack could no more control the components of players’ PCs than he could the graphics card manufacturers – and Rage’s release was tarnished by complaints of ‘texture pop’.

“Architecturally he was frustrated with what he could do,” Romero believes. “He just couldn’t go beyond the video card. So then it’s like, ‘Gotta do something new tech’. And VR is the new tech.

“Then he doesn’t have to work with a game team, right?”

It’s been 21 years since I made a DOOM level. Here’s my version of E1M8 using DOOM1.WAD. https://t.co/ueKM7gBbXd pic.twitter.com/NlmA9aIALN

— John Romero (@romero) January 15, 2016

In January of this year, after a 21 year break, John Romero released a Doom level. The designer had kept abreast of the game’s eternal modding scene, but kept things simple. He picked a level editor, Doom Builder 2 – “a much better tool than the one that I wrote” – and designed an alternate E1M8 that could slot into the first episode as if it had been built at the time.

“It was really fun, ‘cos it was so easy,” he says. “Starting to make a level was just nothing, because I did this for years.”

The result is filled with nods to past Doom tricks: irresponsibly-placed explosive barrels and, as in the original E1M8, the shock of two Barons of Hell – hoofed and horned, each hurling green fireballs. Everywhere, there’s a familiar trickery in the design. As if its creator was toying with the player, like a particularly devious Dungeon Master.

John Romero chuckles. “I think the way that I design levels makes you feel that way.”

Look here to find all three parts of thelife and times of John Romero in one place.