What could possibly be worth $93 million? Well, think of it this way: Cloud Imperium now have a scan of Gary Oldman doing duckface. Somewhere on record there’s a Gary Oldman grimacing; a Gary Oldman pouting; a Gary Oldman pulling his jaw back into his face so that the tendons in his neck stick out. Thanks to Ryse veterans 3lateral, the Star Citizen studio now have a tool that allows them to do with Gary Oldman’s face what we did with Mario’s back on the N64, pulling it this way and that like Oscar-nominated putty.

For more star names, check out the best PC space games.

The point of all this Gary abuse is that performance capture doesn’t have to mean only watching movie-like monologues, like the one Oldman’s Admiral Bishop delivers to the United Empire of Earth senate. Cloud Imperium intend to turn their actors into reactive NPCs. Personalities who sit down in the canteen of the UEES Stanton for lunch at 12 o’clock, and who run to man the guns in an emergency. Characters who roll up their sleeves to help with repairs in the aftermath.

In Squadron 42, they plan to turn out a single-player game that tells a story worthy of Wing Commander, and preserves the player freedom of Star Citizen’s space sandbox.

“You see that speech on a big monitor in the game, but literally 95% of the performance capture is all for the player to interact with and depending on what the player does and so forth,” says Erin Roberts, the campaign’s director. “We want players to take little actions which will cause stuff to happen.”

Chris Roberts played down the scale of Squadron 42 in Star Citizen’s initial Kickstarter campaign, pitching a branching series of missions in the Wing Commander vein. But younger brother Erin and his team have set aside huge tracts of space for those missions to take place in.

“You get to go, ‘I’m going to clear off over here and just check this out on my own because I want to’,” he explains. “It’s not like the old Wing Commander where when you take off you go to this point, this point and this point. You take off and you’re in space – you’ll have lots of different locations you can go to.”

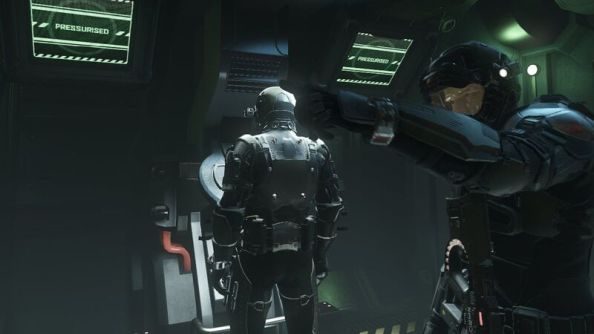

Foundry 42 – the Wilmslow and now Frankfurt studio formed to put the campaign together – are constructing their areas from sets: 10 or 12 styles of high and low tech environments which allow for the swift assembly of ships and stations you’ll be able to tell apart (“So people don’t feel like they’re going to the same old places, which happened a lot in the old days”).

But how do you lend a story in a universe like that structure? As it turns out, Foundry 42 are leaning heavily on that ‘squadron’ conceit. You’re in the navy, and the navy don’t fly off willy-nilly when the feeling takes them.

Turn your back and walk out on the commander during an important ship briefing and you can expect to be arrested and thrown in the brig. Fly way off-course on an important operation and your leaders will “get pissed off with you”.

“There are decisions that you can make but there are consequences to those decisions,” expands Roberts. “[Although] there’s going to be a lot of opportunity for the player to just explore stuff so you get a lot more freedom than you generally get in a story driven game.”

The studio are keen to leave players plenty of room to manoeuvre when it comes to missions – mixtures of extraplanetary and on-the-ground encounters that might go very differently depending on what vehicle you choose to show up in, who you show up with, or whether you choose to go quiet or loud.

When expounding the possibilities in Squadron 42, Erin Roberts is liable to get carried away. In one moment, we’re talking about the long memories of the crew aboard the Stanton, your de facto family for the duration of the campaign. In the next, our conversation is entering the atmosphere of alien planets where, he says, the behaviour of the locals will alter depending on whether or not they’re getting enough minerals, or the population’s in decline, or the economy is failing. The universe he describes is an invisible network of interlocking systems, and you can see the DNA of Richard Garriott’s Origin Systems seeping through, where both Roberts brothers got their start at the turn of the ’90s.

It’s a simulation-first philosophy of game development that’s left a trail of beloved, broken PC games in its wake; playable testaments to ambition unmatched by publisher patience. But perhaps things are different this time. For once, the Roberts’ paymasters are wholly invested in their vision.

“I’ve been doing this over two years and I still can’t get over the fact that I don’t work for a publisher anymore,” says Roberts. “I work for a community and my job is to keep on showing them all this cool stuff. That’s miles more pressure than working for a publisher, because these guys put their faith in us and you want to repay that.”

What’s more, Erin has the technical weight of Star Citizen behind him. Foundry 42 are drawing assets from the huge MMO-in-testing, as you might imagine, but they’re also looking for opportunities to gather feedback. There are plans to feed sample combat encounters into the Star Citizen alpha as it evolves, collating opinion on what might work well in single-player.

“It’s almost like our beta,” Roberts explains. “With the Large World stuff we basically have the ability for people to go in there, play stuff and tell us what they like what they don’t like.”

Squadron 42 isn’t best thought of as one component of a larger game. In fact it’s not even one game: Roberts reckons there’ll be at least three triple-A titles released over the course of the next few years.

“It got to the stage where we wanted to do it in one game and we just looked at it and it was just getting insane,” he says. “It was hundreds and hundreds of hours.”

The Roberts brothers have the plotline for each episode already fleshed out, along a backbone of interstellar politics reminiscent of 2003’s Freelancer. The script for the first installment alone, next year’s story of a rookie earning his wings, is 700 pages long. Large enough that Roberts expects players will need to fly through the campaign two or three times to receive everything loud and clear.

“I guess we kind of expect people to just play it and then play it again to see what they missed out,” he muses. “You plan the original campaign for $6 million and you’re not going to make the $6 million game when you’ve got $92 million.”

After Privateer and Starlancer, Erin spent the best part of a decade directing and producing Lego games – before Chris called him back to the world of very-high-end PCs. For him Squadron 42 isn’t so much a blue sky project as a punt into the outer atmosphere.

“I love the space genre, I love doing this kind of stuff,” he says. “I’ve got one big big thing left in me. I’m getting on a little bit and this really is for me almost like the pinnacle of a challenge. Yeah, there’s a lot of stress. There’s a lot of work. There’s a lot of people who feel like it’s impossible to do.

“So we’re just going to work away on it and keep getting stuff out and showing people. It’s a really exciting time. Right now there are little smiles in the faces of the people in the offices because we know we’re doing well.”