From a studio made up of people who’ve never released a videogame before, The Town of Light – a Unity-engine game that delves into the recent history of the mental institution – is a brave first step. Of course, we’ve all explored abandoned asylums before, but The Town of Light veers away from the typical tropes associated with its setting, instead telling a more grounded story.

The medieval town of Volterra, Italy, is nestled at the top of a mountain that’s prone to creating landslides onto the roads that wind their way to its peak. This town once hosted one of the largest mental institutions in Europe: Volterra Asylum, the inspiration for The Town of Light’s meticulously modeled setting. It was here where I got to speak with the game’s creative director, as well as some mental health professionals, about the history of the institution and the game’s inspirations.

First, Giampaolo di Piazza, psychiatrist at ASL Toscana Centro and vice president of the Italian Society of Phenomenological Psychopathology, spoke to me about psychosis and its symptoms. He told me that sufferers can experience hallucinations – a visual effect often overused in videogames – but generally their brain just interprets the world a different way. He gave the example of a wardrobe: for us it’s an object we can put things in, where for an ill person it could be a prison they can be placed inside.

As you explore the abandoned hospital grounds in The Town of Light you pass by many interactive cupboards, but here they’re not hiding spots to skulk inside while a monster stalks the asylum corridors. Like a person suffering psychosis, The Town of Light shows us the familiar, but from a different perspective.

Likewise, the game was born through the eyes of someone looking at it from another angle. The creative director of LKA.it, Luca Dalcó, has worked with Unity before, but he did so outside of games, creating interactive backdrops and ambiance for theatre, museums and Italian Heritage.

The Town of Light started to form when Dalcó visited Volterra and came across a section of the abandoned Volterra Asylum, partly reclaimed by nature, dilapidated, crumbling and lonely – the building resonated with him. Originally he wanted to create a tech demo to show off how powerful Unity can be for building environments, developing something akin to virtual urban exploration.

Suddenly, people were saying how much they liked it, and the idea began to take root, so Dalcó started thinking about how they could create something more interesting – about the location, its history, what the mental institution is… what it was.

Though Dalcó has no background in storytelling, he and the small team began to research Volterra Asylum and the state of the mental institution between the ‘30s and ‘70s, uncovering forgotten horrors along the way. Patients were stripped of their belongings, human rights, and eventually their very identity. These were lost people, made invisible by an asylum that housed over 4,500 other patients, with little hope of release.

I spoke to a social worker called Angelo Lippi who worked at Volterra Asylum from the early ‘70s, a time when the system was beginning to make breakthroughs in the form of the ‘Humanisation Project’. At the time he worked there, there was one social worker per 400 patients, so it’s difficult to imagine the workload he faced, connecting with the patients and making sure their letters actually went to family members – something that rarely happened prior to him starting.

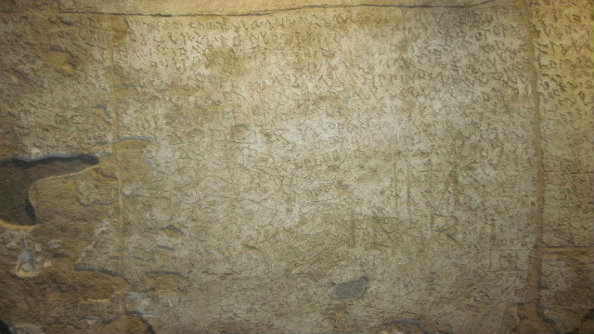

He spoke fondly of his time at the asylum, sharing anecdotes about the many patients who left their mark on him. One loved-up patient used to leave bouquets of vegetables on the car bonnet of a staff member every day, and another used to scrawl strange runes into the asylum walls, with the now-famous etchings stored in a local museum.

But there was a dark side to Lippi’s work: he witnessed a murder and two suicides while working at Volterra Asylum, and this was after the introduction of psychopharmacy introduced pacifying and calming medication to mental care. During the ‘30s and ‘40s, psychopharmacy didn’t really exist.

It was in delving into this period that created Renee, the protagonist of The Town of Light. The research became a fascination for Luca Dalcó, and he kept digging through this period in time, uncovering more and more stories, until he had built up a fictional character in his mind. From this picture, Dalcó wrote a book detailing Renee’s entire life, using real-life experiences as a baseline for this fictional character.

The Town of Light tells just a portion of this life story, showing a modern Renee revisiting Volterra Asylum in a bid to remember what happened to her during her incarceration at the age of 16. Renee is a troubled individual who is so disconnected that she often refers to herself in third-person, and the game is about her sifting through the past to discover the secrets that are buried deep within her psyche.

It’s an interesting premise, and it turns the abandoned asylum trope on its head. It’s unsettling instead of being scary, you’re curious instead of being frightened, and you’re uncomfortable because of the source material, not because of the jump scares.

More games are approaching difficult subjects these days, including mental health, but there aren’t too many that dare to take on a subject as raw as sexual abuse – something The Town of Light tackles – particularly when the character of the story is 16-years-old. But Renee’s experiences aren’t fabricated, and the team didn’t want to shy away from tackling subjects just because they were difficult, or because they are worried about the reaction.

“We are worried, but that’s not a good reason to not touch these subjects,” explains Dalcó. “We tried to approach the communication in a very respectful way. There was an attention to what we communicate: not saying it’s a horror game, but mentioning it’s about a mental asylum, and also adding a disclaimer to the beginning.”

It’s also worth noting that the developers haven’t courted controversy, they haven’t tried to encourage the media into creating sensationalist headlines to build a controversial buzz around the game. “There is stuff that can be spinned, but we’re telling a story of a realistic character who existed in a place where there is still a stigma attached to today,” Dalcó explains.

For a first game from a new studio, it’s a ridiculously ambitious project, not only painstakingly recreating a real life environment, but also trying to portray real, harrowing experiences, and attempting to do it all respectfully. It’s not a task I envy, but I’m glad there’s a studio attempting to create something that provokes more of a reaction than a twitchy squeeze of a virtual gun trigger.