Pick any two Ubisoft earnings calls from the past couple of years – they’re all public record – and you’ll notice a familiar refrain emerge. Every three months, the publisher’s investors would call on Yves Guillemot to slash Watch_Dogs’ R&D costs. And every three months, the mild-mannered but steely CEO would politely refuse.

Those R&D figures represented the cost of doing something new at the bonkers scale Ubisoft routinely work at. Between 2009 and 2014, Watch_Dogs wasn’t just about NPC manipulation – it was a hardcore numbers game.

Try 98 motion capture sessions with 64 cameras – at a rate of two working days a month for five years. Or two new consoles with 150-200 MB of memory – more than enough to dislodge the last generation’s cap on animations, and bring in ballooning team sizes and spiralling budgets to match.

And in the face of it all, Ubisoft Montreal. A Canadian studio with a headcount of over 3000 and the audacity to make the maths work.

Watch_Dogs began as Project Nexus – the work of a tiny pre-production team in Montreal with a mandate to kick off a new series for Ubisoft. It was a rare opportunity for those involved to be exempt from the great publisher production cycle for a little while. To simply sit and design.

Animation director Colin Graham had worked on Naruto: Rise of a Ninja – “pretty much the opposite project in style and execution” – and joined a small gaggle of devs who’d come straight from the radically-conceived Far Cry 2.

The team grew like a katamari over the following months, absorbing talent from all corners of Ubi Montreal – Avatar and Shaun White Skateboarding, Assassin’s Creed and Splinter Cell.

Graham describes a process far from the factory culture Ubisoft are sometimes accused of, which saw experienced groups of devs pulled intact from one project to another. Large chunks of their games came with them – like Watch_Dogs’ auto-cover system, which originated with Splinter Cell: Conviction’s programmers.

Early prototypes revolved exclusively around driving and shooting. The hacking came later.

“When we started Watch_Dogs, the iPad wasn’t even a commercially-available product,” notes Graham.

But the team knew they wanted to get vigilante evasion right, and played countless games of Scotland Yard – the classic board game in which a team of players cooperate to track down a player-controlled criminal on the streets of London.

As they played, the team gradually defined the principles of Watch_Dogs’ felony system. They found that the game became much more compelling if the criminal player could hear the machinations of their would-be captors.

“If you listened, you were actually feeling a lot of contempt for the other players,” said Graham. “You were like, ‘You guys are idiots! You don’t know where I am’. And it was a very satisfying experience.”

That pathetic fallacy manifested itself in Watch_Dogs as police chat – which often tells the player in advance if the cops have lost track of them, or are preparing to ram them off the road. The devs also found that those nudges helped counter the unusually aggressive AI they’d developed.

“They love murder, right?,” said Graham. “They just love to gang swarm you and they’re super evil. Even the cops.”

An entirely separate team was built to handle civilian AI. Ubi Montreal were determined that NPC interaction wouldn’t be an afterthought.

“Typically in the games I’ve worked on in the past, people would always say, ‘Oh we’ve got three months until we ship the game, we need to put some civilians in our world’,” said Graham. “Well, we thought that we wouldn’t be using the potential, especially of the new consoles.”

You can witness the work of that team in the finished game by following the bog-standard citizens of Chicago about – the “walkers”, who stumble, sneeze and change their minds as the player looks on.

“We put a whole system in place for people to do different actions as they walk,” explained Graham. “You have walkers and you have enticers – basically the people who are already spawned in place doing interesting things.”

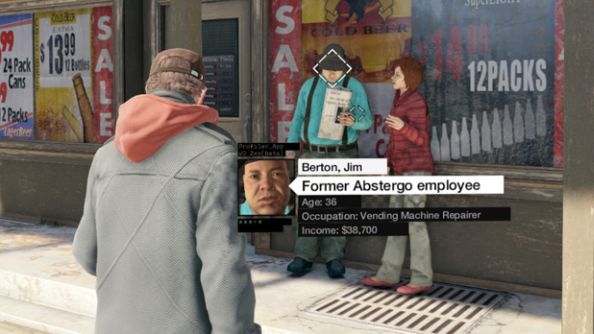

The enticers were emblematic of the dynamic open world the team had begun to conceive. The people of Chicago would be a pool of latent missions just waiting for the player – and hacking would be the means to access them.

It’s easy to forget the visual impact of the characters Ubisoft Montreal have created. Sam Fisher, the balletic beefcake with a trio of all-seeing emerald eyes. And The Assassin, hooded and fading fast into the crowd.

The Watch_Dogs team were under pressure to deliver another just as distinctive. But the protagonist they’d decided on was, to say the least, an antihero – “the weird guy standing in the corner fiddling with his phone when something bad happens”. And with E3 approaching, the specifics of Pearce’s “reclusive” shoegazing persona hadn’t been decided.

“We had this coat that the character was wearing around him, and we were coming up to the demo in 2012 and I was having lunch with some other animation directors,” said Graham. “We were standing around inside the restaurant, and it’s cold in Montreal so everybody’s got their hands jammed in their pockets and they’re hunched over a little bit. Everybody had character and attitude, and I thought, we’ve got to do this for Aiden.”

Graham returned to the studio and asked his animators if pocketed hands were doable. And they were – with a spot of amputation.

“We do a neat little trick,” explained Graham. “When the hands go into the pocket, we scale the fingers down to zero so they get chopped off. But that means they don’t stick through the outside of the coat in extreme circumstances.”

The animation team prototyped the vanishing fingers, and Graham took them to Watch_Dogs’ production manager.

“We sold the hell out of it,” said Graham. “We used the word iconic a lot because, I don’t know why, it just makes people think it’s better. And before you know it, that feature is now so important to the game that it can’t be cut.”

By the time E3 2012 came around, the dev team had exploded to 170 people – each with their own idea of what the game was going to be. Only when asked to put together a piece of continuous footage were they forced to converge on a vision.

“A lot of developers don’t like to do E3 demos, because they take a lot of time and production,” said Graham. “But it came at a really good time for us, because it helped us say, ‘That’s what we’re going to make. That’s the look and feel of the game’.”

It was here that Ubisoft Montreal finalised Aiden Pearce’s clothes, movement, weapons and tactics – and determined exactly what Chicago and its civilians would look like.

It was also, to hear Graham tell it, a terrifying time. Until that point, the demo and the game had been kept secret even inside Ubisoft (“We have a habit of leaking our own stuff”). The team had no idea whether or not their concept of a CCTV-controlled Chicago would capture the public imagination.

“We were actually just hoping people wouldn’t say any bad things about it,” remembered Graham. “We were not expecting people to like it as much as they did. It was a big moment. I don’t know if we’ll ever quite do that again.”

After E3, the baton became the star of Watch_Dogs’ trailers – a black, extendable melee weapon conceived as “marketing porn”.

“We wanted to have something that was louder and faster,” said Graham. “Something very basic, like a beer commercial, to get [the marketing] guys really excited. They could make lots of trailers out of it and they could convince everybody that the game’s badass.”

But Graham was struggling to convince even the Watch_Dogs team that the baton was a deadly weapon, rather than a “tool for security guards and old grannies”. So he went out and bought one.

“I walked into a meeting, a pitch, and I had it tucked in my pocket,” recalled Graham. “I opened it up and smacked it on the table. It was really loud. I passed it round, and nobody argued with me after that.”

Pearce might not have wound up one of Ubisoft’s more relatable protagonists – but Graham points to Watch_Dogs’ cosplayers as proof of the character’s success.

“There are a couple of really nice fan videos of Watch_Dogs, and they actually get the stance, the posture, the way he holds the phone, they get everything right,” he said. “If we had weaker concepts, they would change the details. But people really get into it and nail it.”

In Aiden’s look and in all other elements of the game, the Watch_Dogs team went out of their way to ensure they weren’t stepping on Assassin’s Creed’s cloak.

That meant no slow-mo jump shots, and absolutely no spinning. Instead, the developers looked to Indonesian martial arts movie The Raid for inspiration.

“In The Raid they pound the crap out of each other and throw each other into the walls, and that’s what we wanted to go with,” said Graham. “We tried to remove flair and add brutality. There’s something powerful about it, for sure, but it’s not elegant either. Aiden should be the uncomfortable violence of a street fight.”

What’s more, every single one of Pearce’s navigation moves is tackled in a fashion outside the Kenway tradition. Of all Assassin’s Creed’s extensive animation catalogue, only the swimming made it into Watch_Dogs.

“You can describe both Aiden and the Assassins as being good at parkour but we didn’t want to cross our own style – because there’s a lot of stuff that’s similar in terms of mechanics,” said Graham.

“Our stuntman is actually more athletic than Aiden is. But we had to slow him down a bit, because he’s actually a little bit too much like a ninja. That would mean confusing Watch_Dogs with Assassin’s.”

Graham and his animators actually spliced two men together to create Pearce: Stéphane Julien, veteran of X-Men: Days of Future Past and 300, and Sébastien Rouleau – a young, relatively inexperienced Montreal stuntman who “had the right look”.

“He’s actually a police officer in real life, so if you ever steal a TV in Quebec and you’re chased by this guy, you’re screwed,” said Graham. “You will not get away.”

Rouleau doesn’t speak a lot of English – so mo-cap sessions involved plenty of pantomime. But over 98 shoots, the animation team tasked with tracking his every motion got to know him very well.

“Who he is and how he moves is Aiden Pearce,” said Graham.

Ubisoft Montreal think a lot about how the player moves. In fact, over several years of Assassin’s Creed, they’ve established a philosophy for it. Where fellow parkour game Mirror’s Edge insists on low-level precision, the Assassin’s series has come to focus on high-level decision-making.

“The high-level challenge in Assassin’s Creed is: choose a path,” said Graham. “You can go anywhere, and you can climb wherever you want.”

The same thinking informed Watch_Dogs’ development – where early questions about a jump button were swiftly answered by an auto-navigation key. The Convinction-sourced cover system, too, asks only that the player figures out where they want to go and times the move correctly. The game is happy to handle the business of fumbling around between boxes automagically.

“My feeling is that it’s more fitting for the fantasy of the character,” said Graham. “Do you want to be really bad at something? I’m supposed to be playing Sam Fisher – he’s a super-soldier, right? Why would I suck at running between cover? I want to do that as awesomely as I possibly can.”

It’s one burden less for the player, but one more for the animation department. For Watch_Dogs, Graham’s team committed themselves to an automatic navigation map that would cover the entirety of Chicago and never fail.

Sometimes, despite their efforts, it did fail. Look no further than the Twitter image now retweeted over 2000 times, which showed Pearce insensitively prompted to vault over his own niece’s grave – a mistake a rueful Graham puts down to an erroneously regenerated nav mesh.

“It can start to get a little bit out of control in terms of the number of animations and variations that you might need,” he said. “But that’s okay, that’s the challenge we set for ourselves. Because we can do that kind of stuff, we will do.”

This attitude to game design – to take full advantage of the kind of budget and headcount very few developers have access to – colours every part of Watch_Dogs. Mo-capping every flailed arm and furrowed brow in a dynamic open world has been a “pain in the ass” for Ubisoft Montreal’s animators – but they’ve done it anyway.

Now that Ubi Montreal have half a decade’s worth of animations and assets, they’re looking to draw more convincing reactions from their NPCs for Watch_Dogs 2. They want to provide more compelling, naturally rippling scenarios for players.

“We just touched the tip of the iceberg,” said Graham. “Our priorities were: get people on the streets, then get them to do interesting actions, and then make sure that they would react rationally.”

If a catastrophic event happens in-game, the current system will often tell NPCs to flee the scene – because that covers lots of different potential scenarios.

“It’s really good at clearing the street,” said Graham. “The next step of that would be figuring out how to bring people back and then create more variety. Not just make people leave, but make them stay and be anxious.”

Elsewhere, Ubisoft are looking to remove a second limitation that prevents NPCs from reacting to two separate events at the same time.

“It’s probably one of the areas we’ll focus on going a lot further with because it’s part of the hacking fantasy,” said Graham. “You want to be the puppeteer and control people.”

That’s the dream that’ll fuel Watch_Dogs across a series of investor-satisfying sequels, Graham reminds us: systems that the player can approach and improvise with as they like.

“Everything needs to be systemically interruptible,” said the animator. “It’s a horrendous cost, that’s why not a lot of people do it, you know? But if we can do it, and we can build a game that other people can only dream about building; if we can build something that everybody has to have because it’s doing something really crazy, then that’s a challenge I’m willing to tackle all day.”

With thanks toPhil Oates and the National Media Museum’s Bradford Animation Festival.