So that’s The Walking Dead finished. Telltale’s zombie click adventure is, with the release of the final episode of season one, categorically the best thing the studio has ever produced. Better perhaps than Bone: Out of Boneville and CSI: Hard Evidence combined. A while ago, after a particularly stressful episode, I wrote spoilerlessly about just how excellent The Walking Dead is and why you should play it. Here, spoilerfully, are some thoughts about what’s happened since then. That is, episodes four and five. With all that stuff that went on, and the ending that happened. So don’t read this unless you’ve finished the thing and are now, for some reason, interested in a meandering and largely pointless essay about it.

Not played it yet? Here’s a spoiler-free trailer for Season One…

I think that, broadly speaking, The Walking Dead is a metaphor for fatherhood, where zombies probably represent the sort of real threats I can only imagine real tiny girls encounter in the real world. I don’t have a daughter or any sisters, so I’m really not equipped to carry this point any further than I’m about to, but I’m imagining the top three fears any good father has for his daughter are:

- Being lured into a labyrinth by a predatory David Bowie

- Getting their hair stuck in a paper shredder

- Having to tearfully instruct them to shoot your face off

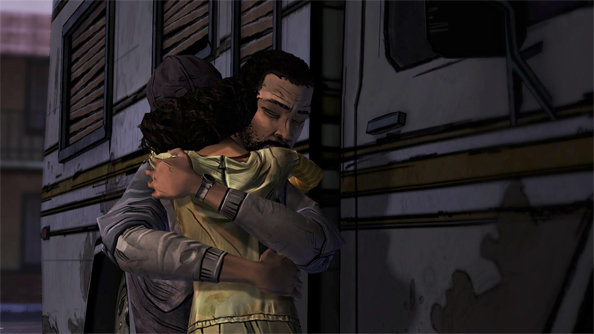

The Walking Dead effectively tackles all three of these father-fears. Clementine is abducted by a just-as-creepy analogue of the Goblin King. She also has her hair grabbed, not by a shredder but by a zombie, which is similarly terrifying. And, most literally, episode fiveconcludes with your grave final instruction to the girl, which marks a relinquishing of your parental responsibility, an annihilation of her childhood and her traumatic, sudden and irreversible brain-shift into the violent independence that will ultimately keep her safer than you ever could.

By that point in the game however, Clementine is already confident enough to pull a trigger. Leave her at the mansion in episode four and she’ll shoot a walker to protect an unconscious Omid. Fail to choke the stranger to death in episode five and, in order to protect Lee, she’ll shoot her abductor in the head. So Clementine’s reluctance to kill Lee before he turns has nothing to do with a kiddy shyness of guns, gore, violence or death — she’s well past that stage — it is absolutely and simply a reluctance to murder a protector and a friend. That the nine year old is capable of ending the life of the game’s protagonist is a victory for the player, who’d been fostering that instinct. Game over, you win.

I don’t think every character had as graceful adenouementas Lee’s and Clem’s. Some of the decision-chickens that came home to roost were awfully clumsy things. Episode five saw Kenny making some odd decisions based on ancient and forgotten conversation choices, almost breaking the fourth wall when the incorrigible arse said he’d been “keeping score”. Kenny, in my game,refused to help search for Clementine and had left me for dead in a previous episode, presumably because I’d sided with Lilly over dropping a salt lick on her dad’s head.

Later, when Ben was dangling from the clock tower, he took the time to peer over a window ledge and cheekily raise his eyebrows as if to say “go on, drop him to his untimely death”. He was well grumpy when I didn’t, slowly disappearing behind the ledge again with a stern look his face. Depending on the choices you make, Kenny’s character can be anything from vaguely irrational to absolutely psychotic. I don’t think he’s supposed to act like that, even taking into account the death of his wife and child.

(There was also that awful puzzle in episode three where you couldn’t get to a map in the train’s cockpit because Kenny was too busy being sad in front of it. God damn, Kenny.)

Christa’s pregnancy in episode four, meanwhile, could only have been more obvious if the baby popped its head out and said “hello boys”. But that particular plot strand goes nowhere, evaporating shortly before the game’s end. Strange too, was that I’d arranged for Omid and Christa to look after Clem once I’d gone to the big zombie horde in the sky, only for the pair to be entirely absent from the game’s ending. And another thing, why did the Crawford doctor in episode four videotape the secret sex-for-drugs trade between himself and Molly in the nurse’s office? And how did the cleaver in the mansion go undiscovered until the precise moment it was needed? Why indeed! There are plotholes aplenty if you stand back to look for them, and as a game that’s more plot than play it should rightfully be criticised for its narrative shortcomings.

But those shortcomings aren’t many. For better or worse, you’ll forgive them.Another theme in The Walking Dead is the dichotomy of surviving versus having something worth surviving for. In almost allhorror fiction, children, the elderly, dogs and assorted loved ones are the loose ends over which survivors most frequently trip. Dogs run into seemingly abandoned slaughterhouses, doddering husbands tumble off ledges, children backflip into coalpits full of of undead rats. They’re liabilities, all of them. Crawford, the ruthlessly draconian and shut-off society discovered in episode four, takes the extreme approach of purging the weak, the sick, the young and old. At the opposite end of that brutal spectrum is Kenny, who lives to protect his family and becomes distant and unsympathetic once they’re gone. Somewhere in the middle is the sorry corpse-couple you discover in their marital bed, dead for weeks in a suicide pact that protected them both from an even worse fate.They’re all reasonable enough approaches to survival, sacrificing in degrees the things worth surviving for.You can even empathise with the bleak survivors logic of Crawford to some extent.

In zombie outbreaks, zombies are so often just a backdrop for what is in fact a story about societal collapse. “Maybe we’re the real monsters” isn’t the point of The Walking Dead, rather it’s the basis of The Walking Dead’s entirefiction. In fact, pretty much anything with a monster in it is simply holding up a mirror to the human condition. We’re a vain lot, us humans, with our conditions and our mirrors and our monster stories that aren’t even about monsters.

Telltale seem to understand this, and I think that’s how they’ve created a Walking Dead game that can not only stand proudly alongside the comics and the TV show, but alongside all ofzombie fiction. The Walking Dead is obviously about the living, not the dead.That’s how they created a character that players not onlyfelt was worth saving and protecting, but one that, in turning a gun onthe protagonist and pulling the trigger,still manages to make us feel absolutely victorious.