While a game engine is technically just a piece of software laying the framework for a videogame, it’s much more than an endless string of code. A good engine is both the heart and brain that makes your favourite game possible, allowing devs to craft their visions and let us run wild in the worlds they conceive.

They prop up every game you’ve ever played, but in some cases an engine can do much more than just ensure we’re having a good time with a game. Think of a major breakthrough in the history of videogames and you can be sure there’s a reliable workhorse of an engine behind it.

It was, after all, groundbreaking engines that made possible the leap to three dimensions, the introduction of completely new genres such as first-person shooters, and even the proliferation of independent games. Engines, if you will, drive progress.

And then there’s the business side of things. A great game engine can turn the studio behind it into a powerhouse, either through the efficiencies and profits gained from sharing technology with peers, or the competitive advantage of bespoke power. The engines listed below did all that, and then some.

Unreal Engine

When Tim Sweeney started writing the engine for a game to rival Quake and Doom in 1995, he couldn’t have expected that it’d be the the engine itself and not the game that would forever change Epic Games.

Unreal turned out to be a great and important game. Its engine, however, started a revolution. The Unreal Engine proved an immediate hit with licensees such as Microprose and Legend Entertainment who had access to it even before Epic released the eponymous game.

By the end of the ‘90s around 20 games were being built on Unreal Engine. In the two decades since, that number has grown so big that it’s hard to reliably pinpoint an exact figure. The committee at the Guinness World Records put it at 408 when it crowned Epic’s baby the world’s most successful game engine in July 2014.

It’s far from just a question of quantity either, as this is the tech behind some of the true PC greats, such as Deus Ex and BioShock, as well as powering franchises including Borderlands and Mass Effect, plus beat-’em-up royalty in the form of Street Fighter V.

The release of Unreal Engine’s most recent poster child, Fortnite, has attracted a whole new wave of creators hoping to replicate its success – especially with UE4 free to use as of 2015 (developers only pay royalties above a certain revenue amount).

Unreal Engine 5’s recent reveal suggests the next generation of this widely usual tool will be yet another game changer, too. Indeed, Fortnite will move to UE5 next year.

Source

Back in the days when every new product from Valve marked a small revolution in PC gaming, the Source engine ranked among the biggest. Towards the end of the development of Half-Life, Valve outgrew the modified version of the Quake engine it was using, and started work on a custom technology.

Counter-Strike: Source introduced Source to the world, but it wasn’t until Half-Life 2, with its spectacular graphics and realistic physics, that we saw its real potential. And yet, despite that, Valve remained the primary user of its remarkable engine.

While Source, albeit modified substantially, has powered some outstanding third-party games like Vampire: The Masquerade – Bloodlines and the Titanfall series, it never really took off with Valve’s industry peers. But Valve’s head honcho Gabe Newell isn’t losing any sleep over it.

“For our developers it works great, for other developers it’s not nearly as useful as Unity. So it’s sort of like, it’s here if people want it,” Newell said about Source 2 in 2017. “It’s not a way to make money for us.”

Unity

Unity is now the engine of choice for indies on a budget. But the technology took some time to get the ball rolling and change the industry.

GooBall debuted the Unity engine in 2005, but it wasn’t until the early 2010s, when games like Thomas Was Alone and a plethora of mobile hits, that word of it spread. By the middle of this decade, Unity was already one of the most popular game engines in the world, accommodating more and more ambitious projects, including indie hits such as Firewatch and Superhot.

Often praised for being easy to use, versatile, and affordable (it’s hard to beat that entry-level price of £0.00), Unity is not going anywhere anytime soon.

id Tech

If there’s ever a museum of PC games, the lines of code from id Tech should be displayed in it, Magna Carta style.

id Tech ushered in the 3D era with the release of Doom in 1993. Six iterations later, it’s still helping to define modern shooters, allowing id to set out its vision for ‘push forward’ combat in Doom and the forthcoming Doom Eternal.

But id Tech’s prospects for longevity didn’t look so hot just a decade ago. Its popularity waned throughout the years until, eventually, id Software’s parent company ZeniMax made it available only to the studios under its umbrella. This exclusivity has done little to harm its profile, however, as projects such as MachineGames’ Wolfenstein reboot series and Tango Gameworks The Evil Within now bear its logo.

Surprisingly, however, Rage 2 didn’t make use of id Tech, despite the game being a collaboration between Avalanche Studios and id. Instead, Avalanche Studios opted to use its in-house Apex engine, which powers the Just Cause series. It’ll be fascinating to see what effect this outside influence has on future versions of id Tech, and its future deployment.

Don’t worry, though – Doom Eternal was entirely built in id Tech 7.

CryEngine

CryEngine isn’t the most user-friendly engine out there, which may explain why few studios other than its makers at Crytek managed to tame it. It’s not the world’s best optimised engine, either – many devs confirm that the stunning graphics it can produce don’t come easily.

But none of that mattered back in 2004 when Crytek redefined the idea of a benchmark PC game with Far Cry, only to push it even further in 2007 with Crysis. The golden days of CryEngine are, arguably, gone, but the tech remains popular with some developers – including Arkane Studios, which used it for Prey.

In a bid for the attention of independent makers, the latest iteration of the engine introduced a novel pay-what-you-want model.

And its legacy runs deeper than you might realise: CryEngine is an important part of Ubisoft’s portfolio, as every Far Cry game since the second instalment uses a heavily modified version of CryEngine called Dunia.

The Dark Engine

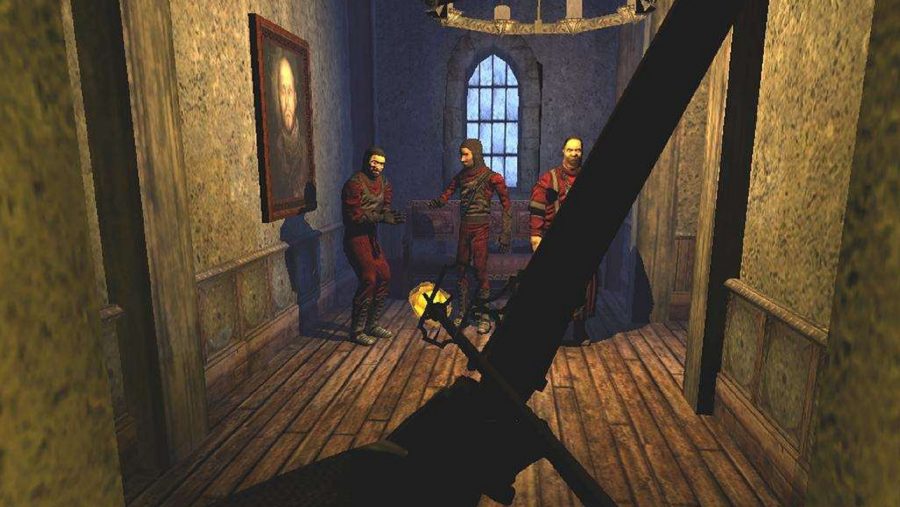

The easiest way to measure a game engine is the visuals. The common belief is that a good engine should produce beautiful games. But graphics, while the most evident facet, are just one sign of an engine’s performance. As a case in point, while games running on Dark Engine were adequately pretty for their time, their primary achievements lie elsewhere.

Thief: The Dark Project, its sequel, and System Shock 2, pioneered the stealth genre as we know it thanks to the advanced enemy AI and sound features made possible by Dark Engine. The aptly named tech gave developers full control of sound propagation within the game, adding much to the atmosphere of suspense.

It also equipped enemy AI with three distinct levels of awareness of the player’s character – vague acknowledgement, definite acknowledgement, and definite acquisition prompting an attack. Appropriately, then, Dark Engine’s achievements lurk in the background.

Havok Physics / Destruction

Havok isn’t like other engines on this list, in that you can’t build an entire game with it. Havok is instead a suite of specialised tools that handle the fun parts of games: explosions, bullets hitting enemies, crumbling buildings, and all that destructive jazz.

To put it simply, if you saw a particularly spectacular show of physics in a game recently, the odds are Havok powered them.

Since its humble beginning in games like London Taxi Racer 2, Havok has gone on to feature in more than 600 games. And none of them exemplify the software better than the Just Cause series. The particular brand of mayhem that culminated in Just Cause 4 is perhaps the best advertisement the folks behind Havok could ever have hoped for.

Frostbite

Electronic Arts needed some time to understand the importance of Frostbite, but once it did, it never looked back.

The engine powering series as distinct as Battlefield, FIFA, and Need for Speed provides a perfect example of the potential that unifying technology holds for big publishers. Multiple studios working on the same engine make it more versatile, efficient, and – relatively speaking – easier to tame.

DICE first introduced its in-house engine in Battlefield: Bad Company in 2008, but judging by EA’s enthusiasm towards it, Frostbite is only getting started.

Infinity Engine

The technology behind legendary games like BioWare’s Baldur’s Gate and Black Isle Studio’s Icewind Dale will forever be a big part of PC heritage. Infinity Engine was a building block for a brand new breed of CRPGs, the golden age of PC gaming, and one of the most beloved studios of that era in BioWare. Few pieces of software had this much impact on a whole generation of gamers.

What’s more, unlike many of its peers, Infinity Engine aged gracefully. In 2016 we saw the release of Baldur’s Gate: Siege of Dragonspear, the first new game powered by the engine since 2002. Responsible for that re-emergence is Beamdog, the studio that handled all the recent Enhanced Editions of classics like Icewind Dale and two Baldur’s Gate games. May this keep Infinity Engine alive for a very long time.