Colossal Cave is an adventure game that predates its own genre and arguably everything we know as ‘the rules’ of modern game design. It began life as 700 lines of code on a PDP-10 mainframe computer in the 1970s, eventually making its way to IBM and Apple home computers by the early ’80s as a ‘launch title’ for IBM’s initial line of PCs. Now it’s getting a second life as a fully realised 3D experience thanks to Ken and Roberta Williams, who credit Colossal Cave with inspiring the launch of their company, Sierra.

“I honestly believe, had I never played it, I don’t know what I’d be doing today. I don’t know what Ken would be doing,” Roberta Williams tells PCGamesN.

The Williams’ legacy is second to none when it comes to PC gaming. Their company, Sierra On-line, was a powerhouse of early adventure games. Roberta designed the breakout King’s Quest series, with Ken programming and eventually leading the company as president and CEO.

In the late ’70s, Ken was looking for a way to get into writing software for the nascent personal computer market. Roberta says that at the time she was “obsessed” with Colossal Cave, which she started playing on a teletype machine before moving to the Apple II the couple received as a Christmas gift in 1979.

Roberta played Colossal Cave until she’d ‘solved’ it: beyond simply finding the way through the maze of rooms, Colossal Cave had – depending on which version you played – 350 points to earn by fully exploring every nook, cranny, and winding path. It was effectively an achievements system, decades before achievements as we know them existed, and she got every one of them. Her fascination with it continued, and ultimately prompted her to start designing her own game.

“I was so surprised by my response to this game, that I just sat down with a big piece of paper and just started scribbling on it,” she tells us. “I put together a game that ultimately became Mystery House, and asked Ken to program my game for me.”

Mystery House, designed by Roberta and programmed by Ken, was inspired by Agatha Christie’s novel ‘And Then There Were None,’ and also drew heavily from Roberta’s experience with Colossal Cave. It was the first game published by On-Line Systems, the company that would become Sierra.

More than 40 years later, there’s a certain sense of poetic symmetry to the Williams’ return from retirement to make a modern version of the game that launched their storied careers. Colossal Cave is an artefact from a time when games were passion projects created by a single person, or at most a small team. Fifty years later, development tools like Unity, Unreal, and RPG Maker, in conjunction with easily accessible digital distribution platforms, have completed the circle and empowered individual creators once again.

As Ken explains it, after selling their stakes in Sierra, the couple had been fairly content to drop out of games and spend their retirement years aboard their boat – that is, until COVID lockdowns went into effect and they found themselves back home, looking for something new to do.

Ken says he’d kept his programming skills relatively current, but decided to learn the Unity engine in his newfound free time. To practise, Roberta suggested he work on making Colossal Cave. “She knew I was working with just me and one artist,” Ken says, “and it was a game that was already designed. I figured, hey, that’s a good idea: it’s a nice, simple little text game.”

Three months later, Ken had finished the programming, and he showed it to Roberta.

“That looks terrible,” she told him.

“Roberta has a very high quality standard,” Ken notes with a smile. “She said, maybe we need to build a team. And we hired 30 people and started writing lots of big cheques. A year and a half later, we’ve got a game.”

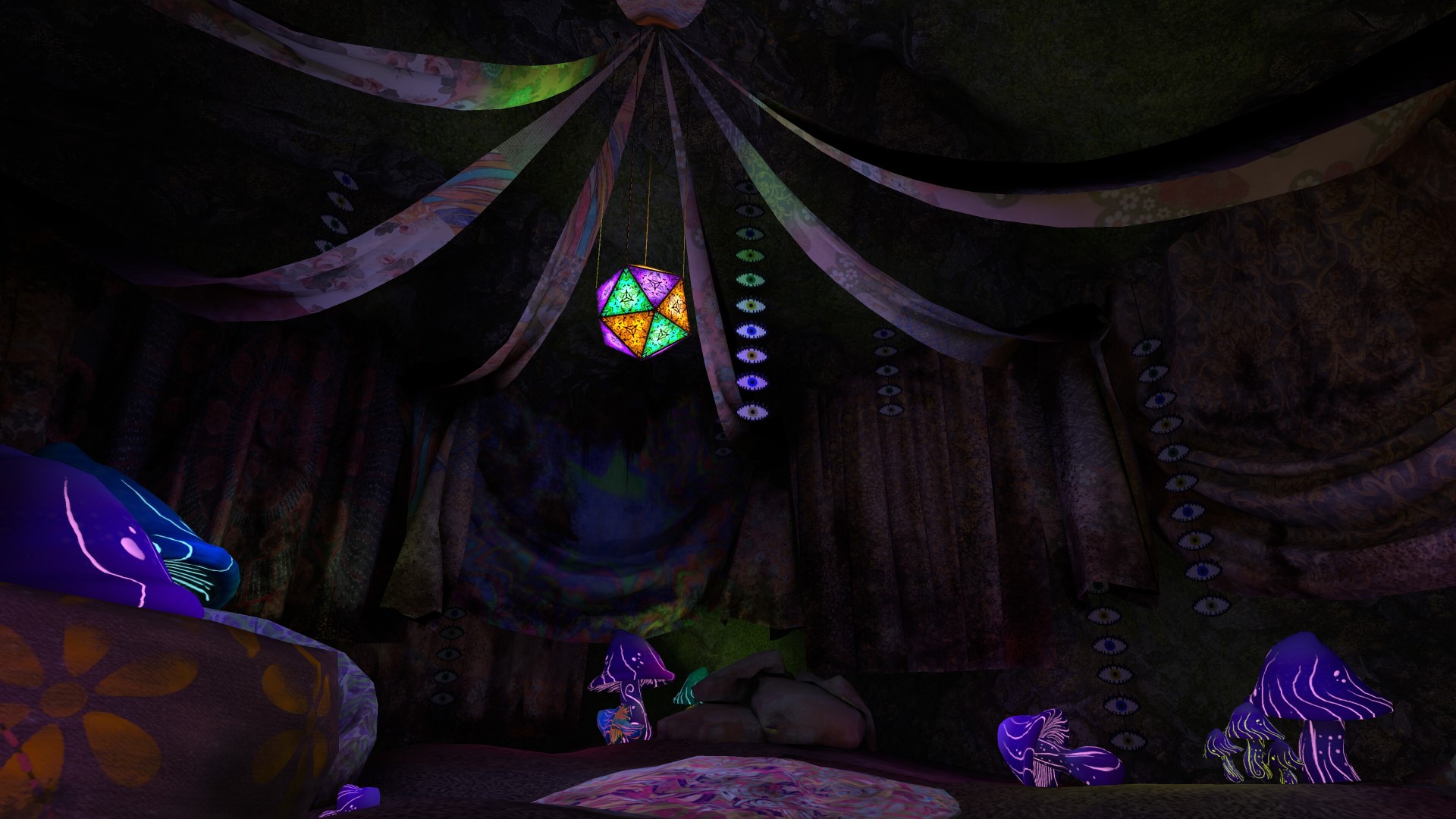

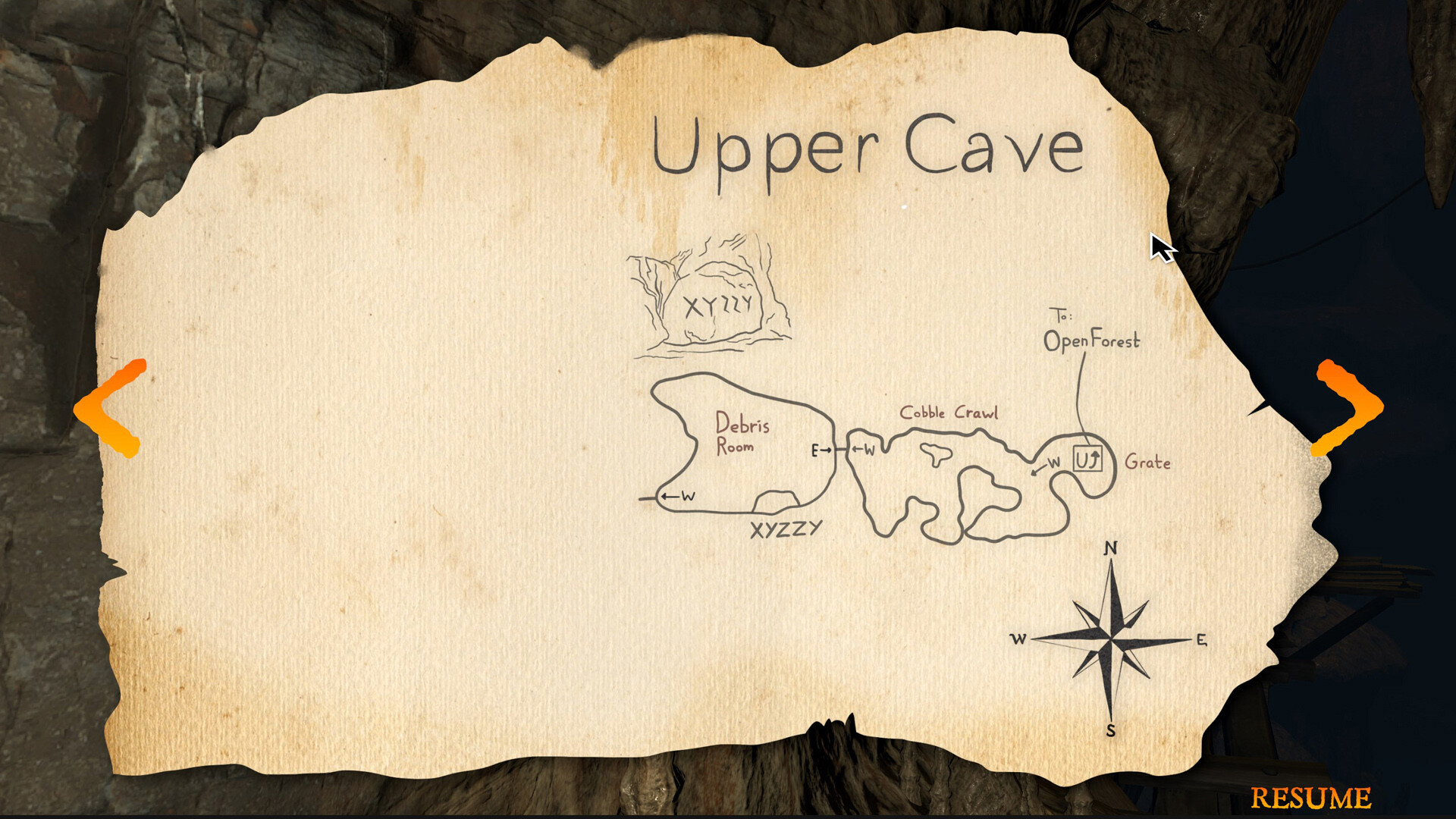

Colossal Cave, despite having a tiny code footprint by modern standards, is a big game to adapt for what is now a highly visual medium. Its pithy descriptions of maze-like rooms rely heavily on the theatre of the mind, and that lets it get away with some clever tricks that were difficult to make visually explicit.

One area is called the Swiss Cheese Room, and like much of Colossal Cave, it’s based on formations original developer Will Crowther found while exploring the Mammoth Cave system in Kentucky. The Swiss Cheese Room is a chamber riddled with little holes, and in the original game, it’s possible to get stuck there for a while: telling the game you want to explore the holes will often simply spit you right back out at the entrance to the room.

“When you go through it, it says, ‘You wander around through some little holes and wind up back in the main passage’,” Roberta says. “But if you do it enough, all of a sudden, you’ll get to the next place.”

The Williamses and their team had to work out a way to get this to work in a game that suddenly has to observe Euclidean geometry. There were countless decisions like this to be made as the couple rebuilt Colossal Cave, making the caverns and passageways they had imagined vividly in the ’70s into a visual 3D space.

“The original game is there, and we’re consistent with it,” Ken says. “But the other 99% of the game is the stuff that we added. And it’s a big game! When we first got into it, I didn’t understand the nuances of the game, the depth of the game, the complexity of the game.”

Ken says he thinks players will have a similar experience when they play this new version of Colossal Cave.

“They’ll be thinking, this is not that complicated,” he says, before pausing briefly. “Well, it will be a hard puzzle. I mean, it’s definitely a difficult game. But you find as you get deeper and deeper into it, there’s a lot of strategy. It’s not really an adventure game.”

“It is too an adventure game,” Roberta exclaims, cutting in.

They’re both right, of course: Colossal Cave was made when notions about what games were called were still in their infancy, and the ‘adventure game’ genre didn’t even exist. Ken and Roberta hadn’t invented it yet.

Colossal Cave is out now. If you’d like to play this remake of one of the most influential old games ever, it’s available for PC on Steam and the Epic Games Store, and a VR version is available for the Meta Quest headset.