At school, we are often told that history is the story of humanity, a grand chronicle of events leading us to where we are now. Our minds place narrative over complex situations in an attempt to grasp a sense of order. This view of history has fed into how game worlds have been built. The ever pervasive concept of a static ‘lore’ being a tome of knowledge that can be accessed and referenced, adding context and depth to a world. And in games we love a rich lore. A big chunky block of information we can wrap around and lose ourselves in.

We are often spoilt when it comes to explaining why things are the way they are in a game world. Codices, wikis, clumsy environmental storytelling; we are given a range of resources in order to understand the virtual world in which we roam. A game’s lore inspires fans to dedicate hours to writing explanations or debating the tiniest details online, figuring out how it all pieces together. When we think of a game world’s history we think of it as a single narrative, a collection of events and characters, with little room for new branches once a sequence has been established.

But history is not an unchanging tome of information. History is constantly privy to the shifting perspectives of society, our unreliable memory, and new pieces of information suddenly shedding fresh light on a situation. For example the ancient city of Troy was widely assumed to not have existed until the excavations by Heinrich Schliemann in the late 19th century proved otherwise.

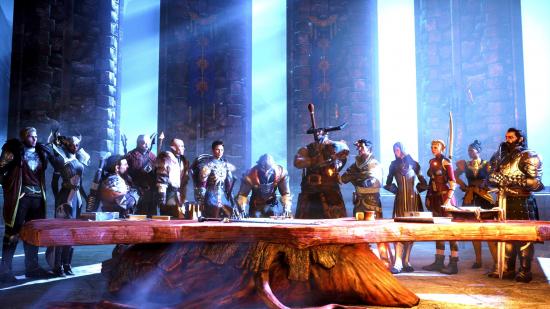

It is a difficult thing to get across in a game, especially in a time when information is readily available at our fingertips – we are used to making queries in a search bar and getting a solid(ish) answer back immediately. Fan-made wikis and arguments over whether something is ‘canon’ only complicate matters. But whether intentional or not, BioWare has managed to work against this friction to create a fascinating example of historiography in Dragon Age, confidently changing its lore over different games in the RPG series, even daring to go against whatever one might consider canon in its games. Dragon Age: Inquisition spoilers follow.

Dragon Age: Inquisition, the third game in the series, makes numerous revelations in regards to the history of its fantasy world. One of the most interesting examples is found in the facial tattoos that certain groups of elves in the games mark themselves with. We are told in the codex and by characters, in both the first and second games, that the Vallaslin – as the tattoos are known – are the outcome of a religious ritual stemming from ancient elven culture, and that the different designs represent various deities in the Elven Pantheon.

However, in Inquisition, we are introduced to the character of Solas, an enigmatic elven mage, who throws a spanner in the works. It turns out that Solas is actually from those ancient times. If the protagonist is an elf and romances him in Inquisition he gives you the option to remove their Vallaslin, as he reveals that these tattoos were not originally done as a show of faith, but were actually slave markings and a sign of ownership.

This twist could be read merely as a way to shock, but it has a more subtle effect on our relationship with the game’s history and the reliability of memory within it. The protagonist, upon hearing this information, can disavow the markings, suddenly going against the consensus of their culture. Or the character can keep the tattoo, acknowledging that whatever the original meaning, it no longer matters, as the unity it represents in their modern culture has replaced it. By changing or adding to the lore here, the writers haven’t undermined the world they have built, they’ve enriched it. We feel the subtle impact not just on a character’s personal decision, but what it might mean for the society as a whole, and how it processes the tragedies and prejudices of the past.

One of the reasons that this change in lore makes Dragon Age’s own history feel real, and not flimsy, is that the information provided to you throughout the series has always been potentially unreliable. The series gives us named sources, therefore making everything in the codex at risk of fallibility and at the mercy of that person’s motives, emotions, and memory. Sources range from oral histories, papers written by scholars of the church and universities, personal journals and letters, popular histories told by bards, and descriptions of material culture and architecture.

Moar lore: The best RPG games on PC

Where a piece of historical information is sourced from within the codex has a huge impact on whether it can be trusted or not. Compare this to a piece of information that is presented to us in the codex section of a game menu as a block of text, with no name or source attached to it – we are led to assume that this knowledge comes from an omniscient writer adding to what is already in the game.

BioWare presents information like this in Mass Effect: Andromeda. Perhaps our natural assumption is that the information comes directly from the game’s actual developer or writer, rather than a character from within the game. When a game’s lore is presented in this way, we tend to leave it unquestioned, as if it were an axiom of that world.

The Chant is essentially the main religious text of the Chantry, the dominant religious organisation. The current version of the Chant is recognised to be a compilation and interpretation of the original, having gone through various iterations throughout the centuries. Not only is this acknowledgement of change within the macrohistory of the Chantry – a fascinating piece of world building – we are also fed the idea that the Chant is subject to variation at a micro level, on a day-to-day basis.

When reciting the Chant to elves, a sister of the Chantry stops to focus on the role of elves in the text, as the audience queries what the Chant has to do with them, showing us the distribution of information being subject to context, and who the knowledge provider and receivers are.

These examples show a developed understanding of historiography, and how this can be utilised to create a rich setting in fiction. BioWare is not the only developer to use unreliable sources in this manner, but the series’ representation of history is one of the best and most interesting in games. It works because history in Dragon Age is not an easy-to-digest list of events, it’s constantly changing, as it is in our own world.

Get ready: When is the Dragon Age 4 release date?

Those who might decry new information coming to light, or our common understanding being challenged as a re-writing of history – as a negative act of betraying canon – fail to understand that history by its very nature is written. It is, and should be, constantly re-evaluated and re-examined. The writers of Dragon Age, however, understand this, and by changing the established lore of their world they not only strengthen it, but incite us to look upon our own history with a more critical eye.