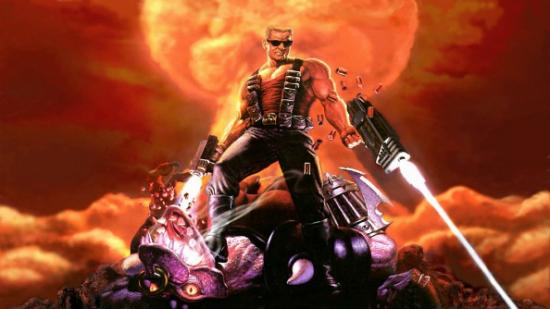

“Damn, those alien bastards are gonna pay for shooting up my ride,” exclaims Duke Nukem, before cracking his knuckles, cocking his gun, blasting his way through a nearby roof vent, and careering down its chute to the alien-infested alleyway below. Themes of “babes, bullets and bombs” to the Nth degree follow in what quickly becomes an unrelenting hedonistic whirlwind of explosions and gunplay, flat tops and biceps, cigarettes and sunglasses.

In 1996, the eponymous Duke as he appeared in Duke Nukem 3D epitomised the over-exaggerated, action movie-inspired alpha male protagonists than were à la mode on the big screen. It’s funny, then, that the man behind the character describes himself as a “typical geek” in his formative years. Twenty years prior, George Broussard cut an antithetical figure: a pocketful of change and amusement arcades better reflected his leisure pursuits against the Duke’s tendency toward firearms and strip clubs.

Broussard would eventually go on to co-found development studio Apogee Software, later known as 3D Realms, with best friend Scott Miller in 1987, who, as a team, co-created Duke Nukem. But in their youth, Broussard and Miller dedicated their weekends to beating cabinet classics such as Space Invaders, Asteroids, Pac-Man, and whichever other games they could lay their hands on.

“Scott and I would run around video arcades with other friends, or hang out in the computer lab at school where you could connect to a mainframe downtown via an acoustic coupler and a printer terminal,” Broussard tells us. “[At home] I had a VIC 20 and a C64 before moving to the IBM PC and the Amiga. I played all the early Infocom games like Zork, Starcross or Planetfall, as well as C64 games like M.U.L.E. or Jumpman. I was a total game addict.

“I also worked in several videogame arcades in the early 80s at their height. I made a couple of small shareware games while Scott was doing his first shareware games. Toward the end of high school we also worked at the same Whataburger fast food joint, then a video arcade called Twilight Zone. This was all a decade before 3D Realms existed.”

In 1991, four years after founding Apogee, Broussard and Miller released Duke Nukem – a 2D-run and-gun sidescroller, a style that was very popular at the time. It was received well, however by the time its sequel rolled around just two years later, the industry was beginning to make the distinct transition from whimsical, two-dimensional sprite-based games to those championing 3D models.

Sidescrollers, it seemed, had seen their day, and Wolfenstein 3D’s release in 1992 further outlined a shift in the gaming landscape towards three-dimensional affairs. Duke Nukem II shipped in December 1993 just one week before Doom hit store shelves. Once the latter arrived, that landscape was altered forever. In a market in flux, Duke Nukem II didn’t sell anywhere near as well as its forerunner, which was the last indication that the Duke’s next outing should take place in a 3D world. Naturally, with this came a host of new challenges.

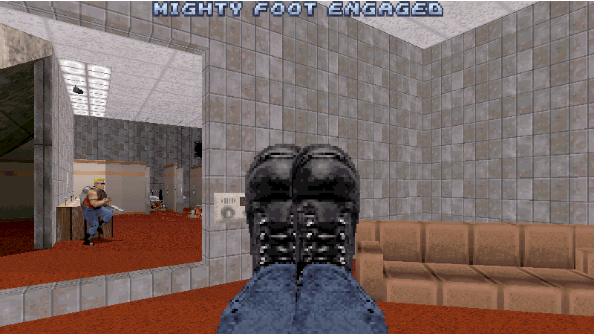

“I’d say we initially set out just to feature clone Doom,” says Broussard of making the leap to 3D. “There weren’t any reference points apart from Doom, really. We were all in uncharted territory. So, you just made things quickly and kept what was fun and what worked, and removed things that didn’t. We did try to push as far past Doom as we could with features like slopes, lots of big moving sectors, jumping, ducking, jetpacking and interactivity. After a while you just have a big toolkit of features and you sculpt a game out of it, test, and repeat.

“Key vision features like Duke talking and real world level settings all came online very late in the process once we had solid footing. I remember us adding the pool table to the bar maybe three weeks prior to shipping the shareware version. None of us had ever made a 3D game before so all we could do was study Doom and veer off the path and see where it led us. You learned as you went. For multiplayer in particular. Things like the wall blowouts were used to open up levels and make them circular and more fun for Duke Match but you had to stumble upon stuff like that through testing and experimentation.”

Beginning in 1994, work on Duke Nukem 3D ran until mid-96 and was overseen by a core team of 15 people. Quality assurance teams, Broussard says, weren’t commonplace in the 90s – “it was the wild west back then” he playfully remarks – thus testing the game fell squarely on the shoulders of the Apogee team themselves.

They’d spend hours “endlessly” testing the game, running multiplayer analysis two, three, and four hours after regular working hours – sometimes two people to test out a gun; other times eight people to stress test a full load. When folk had completed their day-to-day work, idle hands were directed towards a keyboard and mouse.

While Doom was Duke Nukem 3D’s main source of inspiration, Broussard et al were keen to force their own style and personality on it, which is evident through its world, its pop culture references and its monsters. Departing from Doom’s extra-terrestrial-inspired narrative and spectacle, portraying a relatable real-world playground meant the team was never shy of inspiration. “Whatever sounded cool” made it in, says Broussard, so long as it was filtered through the lens of not being too serious.

What made Duke Nukem 3D stand out most, however, was the Duke himself. Until the 11th hour of development, the protagonist was silent, much like the majority of other games at that time. Renowned voice actor Jon St. John was brought on board to bring the Duke’s anger and comedic sensibility to life.

“I remember this vividly,” says Broussard. “Full Throttle came out mid 1995, and I loved LucasArts adventure games and played them all. One night in front of my house at midnight, myself and Jim Dose (who was a programmer on Rise of the Triad) were talking about Full Throttle and how Ben sounds like what we thought Duke may sound like. A lightbulb went off. I did some research on voice casting and we found Lani Minella in San Diego and told her what we wanted. I had recorded the intro from Full Throttle on cassette tape and said “I want a guy that sounds like this”. She said she knew a local radio DJ and called him in to do a demo and he read the lines from Full Throttle. When we got the demo back we said “that’s it!” and that radio DJ was Jon St. John.

“After that I just started writing lines and Duke’s attitude emerged. We would gather at my house and watch movies like They Live or Army or Darkness just for kicks but while watching some of those lines jumped off the screen. All in all I think Duke says maybe 100 things in the game and maybe 5-6 were homages/references from movies. We thought it’d be cool for the players to pick up on. Once the voice went in the game transformed. It all clicked. It felt new and fresh. But Duke may never have talked if I hadn’t played Full Throttle and had that conversation with Jim.”

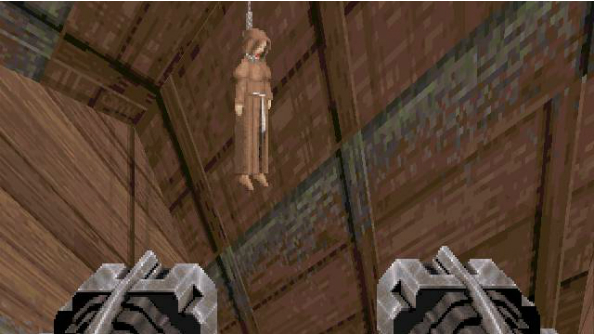

Although it enjoyed huge commercial success upon release, Duke Nukem 3D’s mature themes were called into question by certain facets of the press. Some found it offensive and morally questionable, while some others thought it to be purposefully tongue-in-cheek. Broussard tells me about a section of the game that was cut before release that referenced the then recent Oklahoma City bombing where Tim McVeigh and Terry Nichols blew up the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma, killing 168 people and injuring hundreds more. He admits this was likely “over the line and too soon” but that he “liked to dance on the edge of acceptable content”.

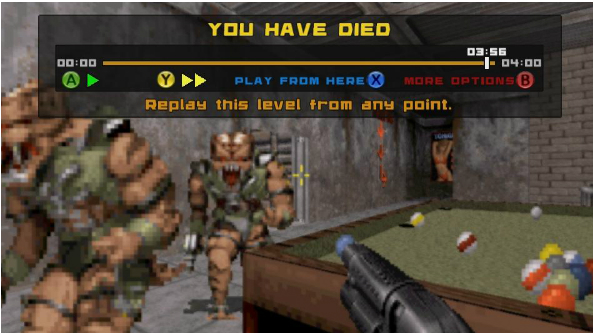

This characterisation is Duke Nukem in a nutshell: a brash, offensive, careless character who made sense within the bounds of a 1996 videogame about killing aliens and blowing things up. He was Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Terminator-meets-John Wayne-meets-Dirty Harry. Today, it’s arguably a different story as Duke Nukem Forever, the direct sequel to Duke Nukem 3D, found out in no uncertain terms. After 15 years in development, several engine changes, being scrapped and then revived, Forever was met with unfavourable reviews across the board – most pointing to the fact that it was grossly dated, both aesthetically and thematically.

“It was just a very hard project,” admits Broussard. “By the time we got to the point where we were actually making the thing, we ran out of road. We stopped working on in in mid 2009 when we shut down. I didn’t touch it beyond that and wanted to bury it in the desert but business realities and complications compelled it to ship and from there momentum took over. It shipped in 2011 the first month it physically was able to. The core issue tracks back to changing engines (more than once) and having technical issues that stalled us. I would never switch engines on a large project again. Ever.”

Although left unsaid, it seems Forever is something Broussard would happily forget entirely, which seems unfortunate given it’s now very much part of the Duke’s lasting legacy. Although he might’ve caused a relative stir after being granted the ability to speak almost 20 years ago, the titular protagonist’s one-liners and off-the-cuff jibes back then pale in insignificance on an offensive level to what made it into 2011’s instalment. Duke Nukem is a name synonymous with video games and it seems almost a shame that it’s not best remembered by 96’s Duke Nukem 3D. Nonetheless, 3D is still fondly remembered by Broussard.

“There’s a few things,” he says when I ask him about his fondest memory whilst developing 3D. “Going to a local gun show and buying Duke’s pistol grip shotgun. I still have that, by the way. And forcing slopes into the game as a feature. It was a late addition and nobody wanted to add them, but they were cool.

“One of the biggest things was shipping. Because the shareware version had been popular, we had something like 50,000 pre orders for the game and we shipped them all out ourselves. We printed shipping labels, packed boxes and made continual runs to the post office for a week to ship them all. Shipping boxes were stacked floor to ceiling. It was some real indie developer shit. It was insane and awesome.”

Broussard adds that no matter how many times you do it, there’s always an element of doubt that lingers before you ship a finished game, that there’s always the fear of showing it to the rest of the world. Nowadays, it’s not uncommon to read that Duke Nukem 3D “revolutionised” shoot ‘em up games when it released in 1996. I ask Broussard if, looking back, he thinks this is true.

“That’s for other people to say,” he says. “But I think it deserves a solid spot in FPS history and it did a lot of things first. I still get fan mail and comments about it nearly 20 years later.”