This article is part of our week-long celebration of Fallout’s 20th anniversary. Make sure you check back throughout the week for more features.

Grotesque monsters. A campy ‘Space Race’ aesthetic. Stories that unfold subtly and organically, based on how you play. A lot of Fallout’s core characteristics we nowadays take for granted. But back in 1997, when a small, now-defunct studio called Black Isle were just starting out, the classic Fallout style was far from recognisable.

Related: the best Fallout companions.

The first game had sold reasonably well, but the critical response had been feverish; hoping to capitalise on the Fallout buzz, Black Isle’s publisher, Interplay, quickly commissioned a sequel. Bigger, better, and with much more for players to do, development on Fallout 2 also had to be completed inside nine months. For Feargus Urquhart, co-director of Fallout 1 and one of Black Isle’s founders, the nuclear heat was on.

“We’d started working on Fallout 2 before we’d even shipped Fallout 1,” he tells me. “That was in the middle of 1997. By the beginning of 1998, when Interplay was having some financial difficulties, they decided they wanted to make Fallout 2 and make it in the same amount of time as the original, and as far as they were concerned, we’d already been developing it for half a year already. So that gave us basically nine months to make the whole game.”

“Fallout 1 was amazing,” continues Eric DeMilt, Fallout 2’s producer. “It really knocked it out the park. But Interplay launched it right before launching Baldur’s Gate, and in terms of revenue, Baldur’s Gate absolutely smoked Fallout – Fallout initially sold something like 200,000 units while Baldur’s Gate sold like a million. And it was a much bigger game. So when we kicked off Fallout 2, there was the ambition to make it as big as Baldur’s Gate, and that’s where a lot of the pressure came from.”

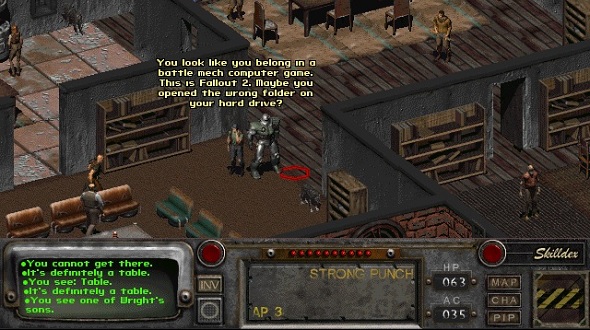

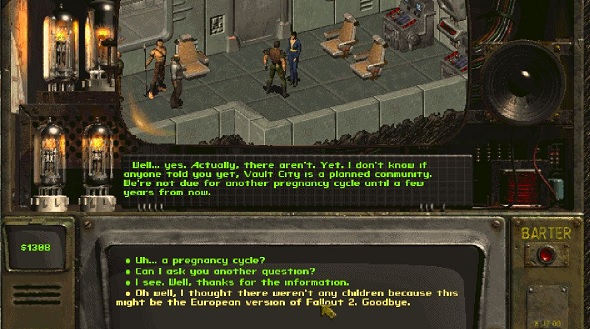

As well as a hectic development schedule, that extra pressure led to Black Isle creating and calcifying what would become some of the Fallout series’ most-famous trademarks. In the case of dynamic, fleshed-out characters, this was on purpose. In the case of bizarre and often hilarious glitches, it was by accident.

“I remember being in a meeting with Interplay’s sales and marketing people,” explains Urquhart, “and them kind of looking at what we had done so far on Fallout 2, and asking ‘well, what’s new?’ They specifically wanted to improve the colour palette, jump from 256 colours to 16-bit. But [Interplay co-founder] Brian Fargo opened up and said ‘look, Fallout is awesome. We’re making more Fallout. It’s like a sequel to a movie. It’s all about the story and the characters’.

“And so we started focusing on an antagonist who, compared to The Master from Fallout 1, would appear in the game earlier on. The player would see him doing horrible things but not be able to interact, and that gave more of a sense of who he was and what he was doing. We also wanted to have Companions evolve a little more, In Fallout 1, the Companions were always the same as when you ‘got’ them. In Fallout 2, they levelled up with you.”

“Another idea,” continues programmer Dan Spitzley, “was giving players this car, where they could store items in the trunk. The way we implemented that was to basically categorise the trunk as a companion – the game would think of the trunk as a companion. But that meant sometimes the trunk would disconnect from the car and kind of ‘walk around’ behind the player. You’d be on the third floor of a Vault or something, and the trunk would suddenly turn up next to you. It turned out to be a huge issue.”

To meet their tight production schedule, designers would often have to draft huge game areas and then move quickly onto the next, leaving vast portions of Fallout 2 sparse or underpopulated, right up until its release date. It was a harried way of working, but it actually helped to cultivate Fallout’s absurdist visual style; with swathes of the map still requiring characters, missions, and other playable material right down to the last minute, Fallout 2’s artists and programmers were creatively set loose, and developed appropriately strange ideas.

“I basically sat down and thought up everything and anything I could to fill these spaces,” Spitzley says. “That’s where a lot of the crazier stuff, like the treasure-hunting dwarf or the Radscorpion that played chess, ended up coming from.”

Characters’ talking heads, seen up-close during cutscenes and conversations, were animated using 3D clay models and a laser scanner – the resulting dialogue sequences, all big eyebrows and facial tics, helped define Fallout’s amusing, chunky aesthetic. To lighten the long, sometimes intense working days, Black Isle’s designers were encouraged to add-in easter eggs, and nods to their favourite films. As a result, Fallout 2 teemed with references to popular culture, as would Fallout 3, New Vegas, and Fallout 4.

From its varied and bizarre cast to darkly humorous writing, several aspects of the Fallout series’ now-famous style were cultivated in Fallout 2. Other Fallout rules gradually emerged. Urquhart and the other directors developed ways to both encourage and direct players’ exploration.

“We had a big map of all of Fallout 2,” he explains, “and we sketched out the route we thought the player was most likely to take, and discussed exactly what quests they were likely to have done, what equipment they would have by that point, and so on.

“If players travelled to an area and didn’t have the stuff we expected them to have, we made it difficult for them to get into that area: the enemies would be too tough, so they would probably turn around and go back. But we could only do that a certain number of times. If players hit too many walls they’d get frustrated and then stop. So another way we tried to kind of compartmentalise player choice, in each area we’d offer a lot of choices, but most of them would only affect that specific area – there weren’t many choices that affected the whole of the rest of the game world. That way the game could still feel rich and we could control the exponential growth of choices. Designers of one area didn’t have to worry about everything the player might do in another. Even today, we still follow the same rules.”

Other lessons were harder learned. As if to illustrate not all Fallout bugs would be weird, funny or cool, when it came to patching Fallout 2, a quirk in the game’s saving and loading system meant that old data couldn’t be loaded into new versions of the game. Essentially, every patch meant forcing Fallout 2’s entire player base to start the game over.

“We worked hard to fix those things,” Urquhart explains, “but a large part of my job, especially for the first six weeks after release, was basically customer service. I put my email address in the patch notes and said ‘if you find anything wrong, email me’. I don’t know how many messages I got.”

Regardless, Fallout 2 reviewed well and made back its budget several times over. Black Isle’s ruthless production schedule, combined with its inventive and unbridled designers, helped solidify the Fallout style we recognise today: though games have gotten bigger and more expensive, Fallout still feels unusual, colourful, and full of new ideas. The Suffolk County Charter School, an area in Fallout 4 where it is revealed schoolchildren were sent insane by eating a hallucinogenic pink ooze, is testimony to the weirdness, humour, and horror influenced by Fallout 2.

“Back then there was collaboration,” DeMilt says. “Our team was pretty small and there were no strict guidelines for how things got done. It was a like a Wild West development style -if you had an idea and could get it into Fallout, then we’d say ‘yep, do it’.”

Check out the rest of our Fallout 20th anniversary coverage:

- How did Fallout 1 ever get made?

- The time is right for a Fallout Tactics sequel

- How Fallout 3 reinvented the dungeon

- Fallout 3’s Vault 101 is perfect

- Making New Vegas was a battle against time

- New Vegas is a perfect fit for Fallout’s dystopia

- New Vegas is the most adventurous Fallout game

- Come Fly With Me is the best New Vegas side-quest

- I became a prisoner of my own Fallout 4 settlement

- Fallout 4’s power armour symbolises how far the series’ combat has come

-550x309.png)