There comes a point in any RPG where the game changes. For most of its running time, it has been about journeys – long, Tolkien-esque treks and the scrapes you got into along the way. But now things are wrapping up it has become almost entirely about destinations. With those fast-travel points long since hoovered up, tasks and their resolutions come into sharper focus. A quest-giver needs a particular potion crafted by the only alchemist in the land? I know that guy. We are mates. I’ll be back in two shakes of a loading screen.

Related: how I learned to start roleplaying someone other than myself.

It is a phenomenon typified by Dragon Age: Origins, a game sprawling in scope which, in its final hours, condenses into an urban tale of political intrigue and throneroom debate – the undiluted choice and consequence that RPGs used to promise on the back of their boxes.

This strange, slow swing from one style of play to another comes about because the RPG is a bastard genre – one whose requisite elements are so disparate they are sometimes at odds with each other. RPGs must let you explore, finding new wildernesses to map and cultures to meddle with. But god forbid that sprawl should get in the way of telling tight, self-contained stories with meaningful payoffs. Or quests, as they are better known.

One way to deal with this conflict is to diminish one element or another. Fallout 4, Bethesda’s best-selling game to date and perhaps the most-played RPG of our time, doubled-down on exploration, streamlining dialogue and character development to the point where it became a divisive issue – especially for those whose last Fallout experience had been the chattily reactive New Vegas.

On the far end of the spectrum sits Subsurface Circular, a game so far from Fallout that its developers do not even class it as an RPG. Yet it is starkly reminiscent of that late-game compression in the genre, where problems and their resolution come to the fore.

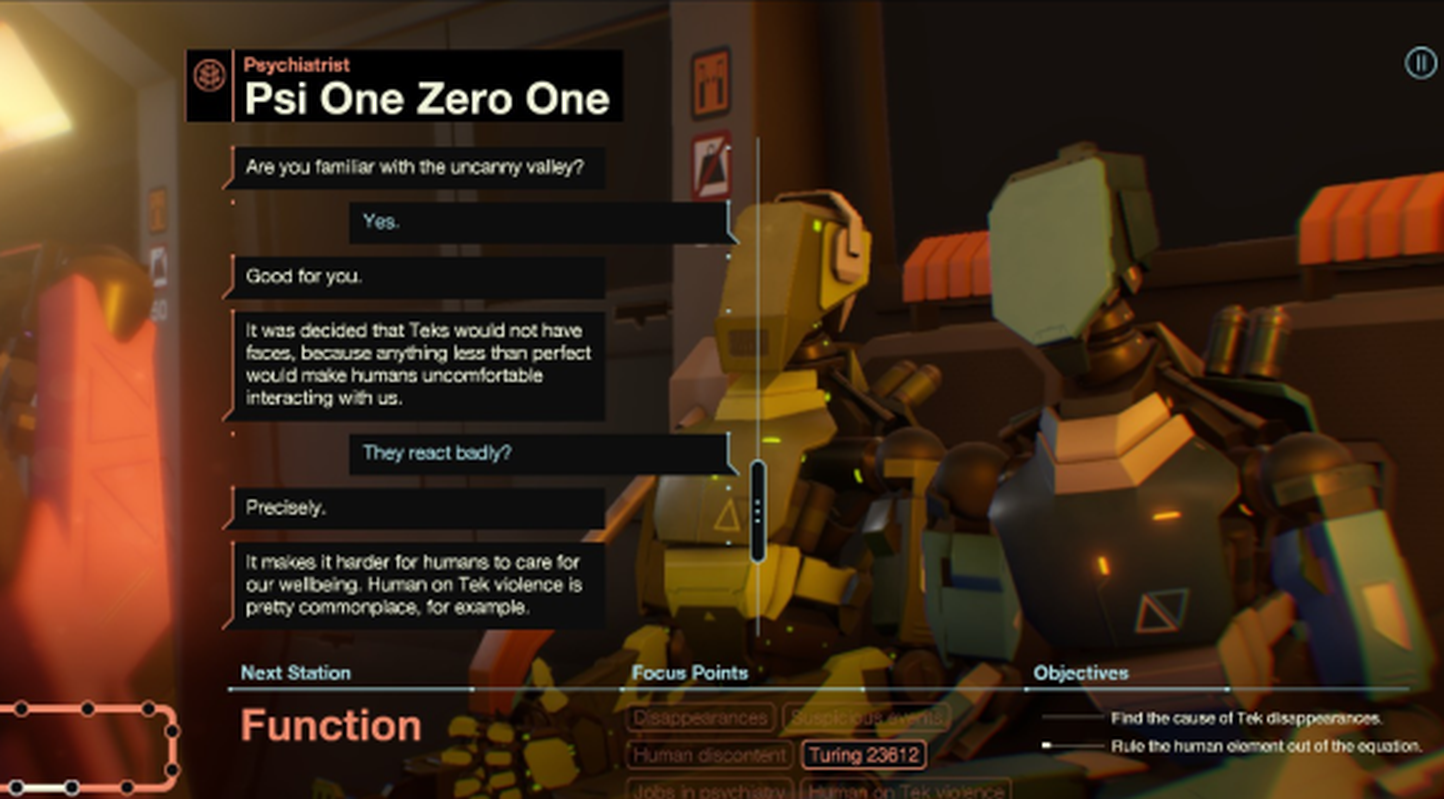

Subsurface Circular comes from UK indie studio Bithell Games, and concerns a single tube ride in a city where many of the most important jobs – manual labour, therapy, police work, babysitting – have become the domain of sentient robots. As a robot designated the role of detective, you are investigating a string of disappearances from the comfort of your seat on the train.

While Subsurface Circular does give you quests of a sort – leads to pursue, puzzles to solve, reluctant helpers to win over – it does not ask you to do the literal legwork. This is its masterstroke: since all walks of synthetic life come through the subway, the game brings critical characters to you, simply shunting them off the carriage once they have worn out their usefulness. By mimicking the mechanical regularity of the London Underground, it finds an economical way to tell a story that encompasses a wide range of perspectives – and evokes that satisfying feeling of the RPG endgame. The teleporting quest completionist can still thrive here but this time they are bound to a single spot.

While Subsurface Circular’s abandonment of genre flab works beautifully, it provides lessons rather than a whole new model for mainstream RPGs. There have always been those players, after all, who shun fast-travel, unwilling to miss the sense of world and adventure the genre can offer them. Perhaps you are one of them. Wanderlust is one of the RPG’s most powerful tools and is not something designers should rush to leave behind.

But just as Fallout 4 is bringing exploration and action to the surface of its RPG soup, others ought to be fighting for the flavours that Bithell’s game exemplifies. Divinity: Original Sin II might well be the finest RPG ever made – committed to storytelling and devoted to roleplaying above all else. But even its developers succumb to the siren call of sprawl, and there is a joy to dense, focused dialogue that is worth protecting and exploring too.