Games, demonstrably, can be funny. Point-and-click adventure games in particular have made a tradition of it, from Maniac Mansion through to Tales from the Borderlands. But the conditions they’re made in conspire to kill comedy. As triple-A team sizes get bigger, the number of voices grows ever larger – and too often, they cancel each other out.

That’s the impression I was given by Nick Bruty – designer of MDK, Giants: Citizen Kabuto and Armed and Dangerous, all commonly cited as rare Funny Games – when I interviewed him last year.

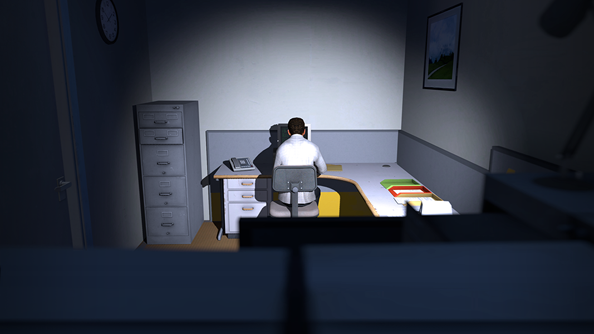

There is occasional comedy to be found among the best indie games on PC.

“Certainly on bigger games, humour is a much harder thing to get through the process,” he says. “On any triple-A thing, you can imagine, there are a lot of people involved with that. And human beings are so subjective, it’s hard for [comedy] to survive a large group.”

Bruty describes a typical design meeting – the kind he’s sat through on many occasions since co-founding Shiny in the early ‘90s. In it, a large group of developers throw around a wild, funny idea, and the room erupts with laughter. And then nobody puts it in the game.

“I think what happens with a lot of games is that people just vet themselves,” he muses. “They say, ‘We can’t possibly put that in, the publisher won’t like it’. My approach is to get it in as fast as you can and see what flies.”

Perhaps this is why laughs are relatively scarce in our Steam libraries – while comedy’s more marketable cousin, zaniness, looms large in a new wave of brightly-coloured MOBA shooters.

But some games are funny, clearly. So how do exceptions like Monkey Island and MDK slip the net?

MDK was bankrolled by a toy company with no prior experience in game production, and Bruty speaks most fondly of the projects on which he enjoyed little to no publisher oversight. He has that in common with Ron Gilbert. Musing on the success of Monkey Island last September, Gilbert praised early LucasArts for knowing to “leave creative people alone”. In fact, he began work on Monkey Island 2 without company approval, before anybody knew whether the first game was going to sell.

“I think that was part of my strategy,” he recalls. “Start working on it before anyone could say, ‘It’s not worth it, let’s go make Star Wars games.’”

Some of the strongest comedic teams in games have been led by these slightly bullish individuals – single-minded enough to push their jokes and leftfield ideas beyond the impasse that is difference of opinion.

A figure like that can help, too, with a second large obstruction facing comedy in games – the fact that these things take a heck of a long time to make. Before Double Fine transitioned into the business of smaller, more frequent releases, they averaged two a decade. Jokes don’t tend to benefit from repetition – and during the development of Psychonauts, the nascent studio heard the same lines blare from their speakers for five years – as if testing some elaborate Guantanamo torture.

While making Portal, Erik Wolpaw and Chet Faliszek switched to foreign language voice acting so they wouldn’t have to hear their own jokes anymore. There’s a point, evidently, where bouncing your ideas off a sounding board starts to look like pummelling.

Having an individual able to act as both motivator and joke advocate seems especially useful when there’s only one metric worth anything comedy – the volume of laughter from your audience. In game development, writers are often years out from hearing any response to their material.

“Tim [Schafer] is really good at reminding people why these projects are cool,” Double Fine’s Anna Kipnis tells Rock, Paper, Shotgun. “Some of these projects are very long. Psychonauts, I think we were still laughing at some of the jokes…”

“I don’t remember that,” adds Wolpaw, Schafer’s co-writer. “I don’t remember much laughing.”

Even once that audience does sit down with a Funny Game, of course, they only go and ruin it. Comedy is about timing, and that’s the one thing you can’t guarantee in an interactive medium foolhardy enough to let the player wander freely. What you can guarantee is that they’ll have pressed play on a holotape seconds before walking over an invisible line to trigger the perfect quip from the protagonist; that they’ll have skipped the last line of dialogue, which happened to be the set-up for the next.

That disconnect between intent and delivery is compounded by the fact that the writer who conceived the joke is rarely in the room when it’s recorded, or sat with the animators and level designers before it’s implemented (a luxury that in-house Valve writer Wolpaw makes a point of exploiting, incidentally).

What rare Funny Games like Portal, The Stanley Parable and Firewatch have in common is a bunch of jokes that are reactive – their timing in response to or even up to the player. In Portal, it’s GlaDOS chiding you for knocking cameras off the walls; in Stanley, it’s unplugging the ringing phone with your wife on the other end; in Firewatch it’s picking up and then dropping disposed beer cans in the Wyoming wilderness (“Fuck it, I’m not the maid”). These moments of sabotage, when a game surprises by acknowledging your actions, are well-coupled with comedy.

But perhaps more naturally still, humour can emerge from a game’s systems. In the interplay of the sound bites and situations in TF2 – or the slapstick fisticuffs of co-op Rayman – there’s no tension between the player and the laughs. Perhaps the reason so many videogames aren’t funny is because people keep trying to write them.

“At strip clubs, there’s a guy whose job is to talk between the strippers,” says Wolpaw. “He tries to do a good job and be entertaining and enthusiastic, but everybody’s just there for the nakedness. That’s a professional writer trick we call called an ‘analogy’.

“What I really mean is that game writers are the game equivalent of the guy who talks between the nude girls at strip clubs. Nobody cares about what that guy does, and anybody who does care is probably a little maladjusted. So I’d have to say the hardest part of being a game writer is learning all the writing tricks like ‘analogy’.”