There is a fantastic moment in Half-Life 2, during the ‘Water Hazard’ section of Valve’s FPS game, when you first arrive at one of the resistance outposts, Station 12. Previously, you – or, if you prefer, Gordon Freeman – have been told that communications with Station 12 have mysteriously ceased. Overlooking City 17’s irradiated river, the Station is supported on stilts. Immediately, you know that something is wrong. The river is silent. No-one exits the Station to greet you. A large wooden container dangles ominously from a pulley – the grand piano over Buster Keaton’s head; some stark realisation just waiting to drop.

When you go inside, naturally, everyone is dead. A couple of levels ago, you saw a missile land in front of you, then open up to release its payload – several headcrabs, used by the Combine to turn the Resistance into zombies. Here, you find the same design of rocket, and a single headcrab still alive. The voice of some far-off Resistance member crackles over the radio: “Come in, Station 12.” Without anybody saying what’s happened, you can piece it all together intuitively.

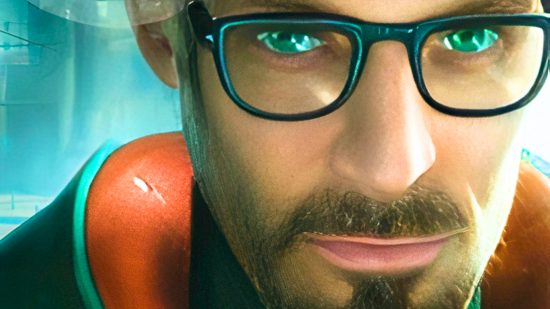

This is where Half-Life 2 excels. We have a simple, sci-fi horror story – creepy building, everyone’s been killed by monsters – but it’s all told without words. If the point of Gordon Freeman as a silent protagonist is that we, as players, can more easily put ourselves in his place, and react to events in our own way, it follows and coheres that Half-Life 2’s story – and it’s small, isolated sub-stories, like Station 12 – are similarly wordless, and understood through our own engagement.

Gordon doesn’t speak. The game doesn’t speak. Looking around, taking things in, and independently finding your own narratives and conclusions becomes one of Half-Life 2’s ‘mechanics.’

But then, just after Water Hazard, you arrive at Black Mesa East. And Alyx is there. And Judith is there. And Eli is there. And they’re all talking to Gordon about the fact they haven’t seen him in 20 years, and how dangerous his journey must have been, and what happened after the events of the resonance cascade. And he just stands there, staring – there’s nothing else he can do.

In theory, I suppose we’re meant to reply to these characters in our heads. “Gordon Freeman!” says Eli. “Let me get a look at you, man.” And I guess we’re supposed to think to ourselves “Eli! So good to see you!” But of course we don’t, because we don’t know who Eli is, or how Gordon knows him – and we can’t just improvise the appropriate line of dialogue and say it in our heads whenever Half-Life 2 commands.

So, you just get these bizarre silences; a character who seems removed and inhuman; and a group of supporting characters who inexplicably adore Gordon, ignoring the fact that he won’t even talk to them.

Perhaps if this impacted just one scene, or one contained aspect of Half-Life 2, it would be permissible – it would be something you could accept, under the agreed rules of suspension of disbelief. But Gordon’s silence, and the rest of the cast’s inexplicable eagerness to see and talk to him, compromises the narrative and the fiction of the game.

It’s hard to feel, for example, particularly sympathetic towards Gordon when he behaves so inhumanely. Not only do we as players have essentially nothing to attach to or recognise about his personality, we repeatedly watch Gordon refusing to speak to anyone, staring at everything blankly, and acting like a bizarre, rude, aloof robot. I don’t think it’s asking too much of a game to make the central character – our avatar, our protagonist – at least somewhat emotive.

Otherwise, without at least a semblance of something, a bit of personality, likeable or not, it’s difficult to care what happens to them. In gameplay terms, the central tension of Half-Life 2 is that Gordon could die – you’d better do well in this gunfight, or you’d better successfully navigate this physics-based platforming section, or Gordon will die. But so what? Gordon isn’t a person. In a lot of scenes, Gordon hardly seems sentient. And while it’s true that his silence and his emptiness allow us to project onto him, and likewise, for Gordon to become an in-universe symbol for the Resistance, that dynamic, too, is skewed by his silence.

The survival of Gordon Freeman in Half-Life 2, and the completion of his quest, becomes a metaphor for the entire battle between humankind and the Combine. He’s a flag. He’s a statue. He’s an icon. To this extent, the character works. The level ‘Follow Freeman,’ where you automatically recruit freedom fighters wherever you go, illustrates how each and every member of the Resistance views and uses Gordon as a blank slate, onto which they can project their individual hopes.

When they see Gordon Freeman, absent of ideas or words of his own, they are able to see themselves. But again, when these people try and talk to Gordon, he says nothing. He is the leader of humanity, but by definition, has no charisma, no vision, and, most tellingly, no humanity. We see the people of City 17 being beaten, queuing for food, sobbing in one another’s arms. In the later levels, under Gordon Freeman’s command, we see them dying in the streets.

And still, Gordon has nothing to say – not a syllable – about any of it. Following your orders, half your squad in the later levels might get blown up by a Combine grenade, and as the other half stand there looking at you, the only thing you can do as Gordon is look back, say not a word, and move on like nothing happened.

A good leader, someone people can believe in and get behind, may well lead with actions, but Gordon Freeman, because of his perpetual silence, can only lead by action, singular – shoot and kill the Combine. It presents you, once again, with these absurdist, absorption-spoiling moments, when all around Gordon Freeman there is spectacular, human drama, and all he does is silently stare.

Half-Life 1 has better writing than Half-Life 2, then, simply because it has less writing. The narrative is more straightforward. There are fewer characters who talk to Gordon Freeman (and, by association, fewer characters at whom Gordon weirdly stares). And there is no emotional burden for Gordon, as a character, to bear or recognise.

In Half-Life 2, we have scenes where Alyx is angry or sad, where Barney is cracking jokes, where Eli is being warm and welcoming – all these small, emotionally driven moments, framed by a wider narrative whereby Gordon is the hope for all humanity. In Half-Life 1, for the most part, he is on his own and with the simple goal of escaping Black Mesa. A physicist and an engineer, who doesn’t talk, and can only interact with the world by opening doors, turning valves, pressing switches, and shooting guns, Gordon Freeman is all action, all practicality.

In Half-Life 1, this is all he needs. The game is designed around his silence. In Half-Life 2, Gordon is confronted by interpersonal, dramatic, and human problems, all of which should be fundamentally part of any game’s story, but his character hasn’t changed. He is a set of socket wrenches and a handgun, that the rest of the cast talk to about their feelings.

Like in Water Hazard, the writing and delivery of story work best in Half-life 2 when they, like Gordon, are wordless. The solution, perhaps, is always to design the Half-Life games (if Valve ever makes another) around Gordon Freeman being by himself. Either that, or just let him talk.

Reading about the classic Half-Life series might have you in the mood for some other great old games. Alternatively, you may want to know whatever happened to Half-Life 3, or maybe take a look at some other strong story games available on PC.