“This is how you died,” Project Zomboid kindly informs me as I make my first tentative steps into zombie-infested rural America and attempt to survive this isometric apocalypse sim. Whether it’s from being eaten by zombies while scavenging in an abandoned house, dying from starvation and dehydration or bleeding out in the forest, far from first aid supplies, the Grim Reaper scratches everyone off his list.

It’s harsh – downright mean, often – and can be a confusing, obtuse mess for those who have not delved into the wiki, but it’s turning into one of the most detailed, feature rich zombie titles out there, demanding that anyone sadistic enough to want to experience the zombie apocalypse must take it for a spin.

I’ve died many times since those words first flashed up on the screen. A day, a few weeks, a couple of months, eventually I cock up. But every depressing, lonely life is a complete story, filled with embarrassing failures and tiny, precious victories. Each game expands the anthology of tragic tales, and the deadly, random world ensures that each attempt feels distinct.

The story of your death begins before you’ve even woken up to see the end of the world. You’ll get your chance to play victim later; first you get to be god. As the architect of the zombie apocalypse, there are a slew of options which tailor the broken down world to your desires. How long it takes for the water and electricity to get turned off, how often survivors find loot, what type of zombies infest the world – there’s little the can’t be tweaked or fiddled with. The only thing that stays the same is the layout of each of the two maps.

With the world conjured into existence, its sole survivor is the last thing to be fashioned. Male or female, different skin tones and a few hairstyles are the limits of the aesthetic customisation, and the simple character models and understated art style makes each person look more or less alike.

Traits are given more attention, with characters’ pre-apocalypse occupations informing particular boons (firefighters start with a handy fire axe and cops are better shots) and a chunky list of positive and negative traits which can be drawn from. Being strong allows a survivor to carry more and avoid getting knocked over, while being gluttonous requires a survivor to eat more – which is a bit problematic when a trip to the supermarket involves wading through the ravenous undead. These traits have points associated with them, and together they have to amount to zero by balancing the positive and negative quirks.

Survivors are born into a world that already seems beyond hope. The towns, forests and farms are absent life, with only zombies walking up and down the streets or hiding in sheds. NPC survivors are in the cards, but have yet to be implemented, giving Project Zomboid an even more hopeless, lonely atmosphere.

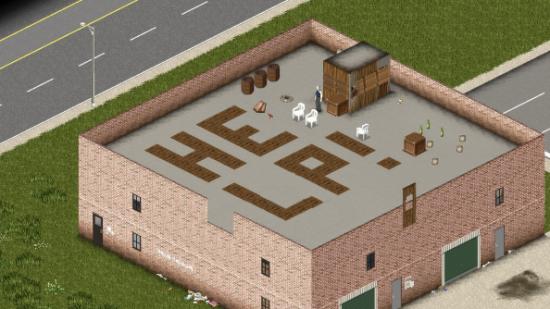

The immediate concern are securing a base of operations, but the whole map is open and guidance is almost non-existent. Common sense and a quick browse through the wiki are blessings, and just traipsing off without any preparation tends to spell an early demise. With a secure base, it’s easier to start planning excursions, looting homes and local businesses for supplies.

Smash and grabs, avoiding fights with zombies if possible, can reward players with tons of loot, most of it mundane, not all of it useful. The trick is in figuring out what to do with objects you’ve nabbed from a ruined home. Clothes can be torn apart to make bandages, pots and bowls can be used to store water for when the utilities gets turned off, sheets hide your presence from zombies while indoors – either looting or setting up a base – and a hammer is your first step in becoming a post-apocalyptic carpenter.

Though survival is the only objective, it’s a complicated goal. Even managing your exhaustion, hunger and thirst levels becomes a challenge in this dying world, as food becomes increasingly scarce and all the tasks demanding your attention stop you from sleeping. The simulation goes as deep as factoring in the effects of clothing: wear a sweater in the middle of summer, and you’ll start suffering from heat exhaustion; go out raiding in winter wearing nothing but a vest and some underwear, and you’ll freeze to death.

Scavenging and slinking past zombies to break into homes and shops can keep you going for a while, but it’s risky and only a short term solution. Eventually the electricity and water get turned off, perishable food goes stale, and the bounties found in empty buildings peter out – then you die. Or maybe not. Maybe you’ve been storing seeds, collecting building supplies, using rain collectors. Maybe you’re in this for the long haul.

Long term survival is the goal, and for that, you need to rebuild. Entire farms can be constructed and maintained, ensuring a more consistent source of food, reducing the need for excursions and encouraging a more defensive playstyle, with the survivor barricading themselves in their fortified farm. Threats persist, of course, from prowling zombie hordes and the annual curse of winter.

A lot of the systems require some fleshing out, with crafting being limited building furniture and fortifications or throwing a bunch of crap into the oven to produce more hearty meals and combat lacking any precision or intensity, but even in their rough state they come together to make a satisfying whole. There’s a lot to do and worry about in Project Zomboid and it makes for a compelling, if not relaxing, way to watch the world end.

But really it’s about the stories. My first death was at the hands of a home security system, wailing as I managed to open my very first window, alerting all the zombies in the area to the presence of this living burglar. Death number three involved barricading myself in a bungalow, countless zombies waiting outside, and starving to death. My last death saw me going on a camping adventure out of town, running out of water, almost dying, finding a bottle of water, and then getting eaten by zombie hiding in a toilet.

There’s certainly work that needs to be done, graphical glitches that annoy, frame rate problems that crop up, guidance that shouldn’t be restricted to a wiki – but it still manages to drag me back to that ruined world, to try and survive one more time. And then another. We have so many zombie games to choose from, yet most remain focused on action. Project Zomboid eschews all of that for thoughtful management and slow burning desolation and misery over jump scares. It’s not a typically fun game, but learning how to survive the upcoming zombie apocalypse is still a worthy way to while away the hours.