“When I was in college I had a job seismic crew in northern BC,” Raphael van Lierop tells me. “Basically, doing seismic surveying for oil companies. You’re flown in to the middle of nowhere by a helicopter and there’s no roads, nothing except for a few logging camps. It’s extremely isolating. I think that a lot of classic wilderness literature has played on those themes; what happens to the veneer of civilization that we all carry around with us when we’re put into a real survival scenario.”

That’s the scenario where van Lierop and his team at Hinterland want to put players in their recently-announced survival game, The Long Dark. It’s a survival game set in the Canadian backcountry in the midst of civilization’s collapse.

That might seem like coals to Newcastle. After all, PC gamers watch civilization falling apart just about every day, and that’s just from reading comment threads. Then they play games involving zombie invasion, plague, aliens, and sometimes even environmental catastrophe. What makes The Long Dark different is that it’s more Jack London than George Romero, inspired less by American urban survivalist fantasies and more by a Canadian frontier that remains untamed, where man is not the real monster, but another of nature’s potential victims. It is a place near to van Lierop’s heart. In fact, it’s practically out his back door.

When it comes to peeling back the veneer of civilization, van Lierop may already have created the definitive work with 2011’s Space Marine. That veneer is hard to maintain when you are controlling a burly man in bright blue armor who is curb-stomping Orks, sending curtains of blood slashing everywhere.

“You know, with Space Marine I didn’t set out to make the most violent action game ever made,” van Lierop says. “It just turned out to be that way because that’s the IP of Warhammer 40,000.”

While I will defend Space Marine to my dying breath (though I am bias), van Lierop seems ambivalent about the project. Or perhaps more accurately, he found himself becoming ambivalent about his entire career in its wake.

“After every game I’ve shipped, I’ve gone through that process of reflection and asking myself, ‘Is this the right thing?’ And after Space Marine it was particularly strong… I got to that point where I reflected back on why I first got into games. What my ambitions were when I started out in the industry. And… it felt kind of like a now or never scenario. It was like, I could sign up for another big triple A project that’s going to be another two or three years of my life, or I can take a shot now, at this moment, and try and see if I can make it happen.”

Time is something van Lierop has become acutely aware of. His time in mainstream game development showed him how slowly years transform into new games, how truly short a career in development can be.

He explains: “If you look back at projects that got canceled, or that you can’t finish for whatever reason, and the games that you do ship but don’t really resonate, you’re kind of like ‘Shit, if this keeps up maybe I’ll get ten games out by the time I’m done, and a couple of them will be pretty good, and the rest will be ok.’ Does that feel like it’s going to be enough?”

Into the wild

For van Lierop, it wasn’t. He departed Relic and started laying the groundwork for Hinterland Games and The Long Dark while working as a consultant on a variety of projects, including Far Cry 3. But it was all to pay the bills while the small team at Hinterland started working on the game they really wanted to make, a game with its origins in the Canadian backcountry and van Lierop’s own connection with it.

“My wife and I moved here out to Vancouver Iisland from Vancouver shortly after I finished Space Marine, largely because we wanted to get out of the city. My office is like 30 meters from 50 km of really rugged mountain biking trails that go through all these log cut areas and forests with cougars and bears and all this kind of stuff. So this is my backyard,” van Lierop explains. “I really wanted to explore that space.”

Van Lierop has left the city behind, and so has The Long Dark. Van Lierop wanted to make a uniquely Canadian game, one more informed by the isolated, rugged communities that dot Alberta and British Columbia.

“I wanted to explore not the end of the world, not the urban apocalypse, which we’ve all seen a million times, but what does the end of the world look like from the fringes?” Van Lierop asks. “What does it look like for people who live in the crossroad towns and small rural communities on the edge of nowhere. How did they become even more isolated than they were before? …We’d like to eventually end up in some of those more familiar settings, but we want to start from this different context.”

On the edges of civilization, the breakdown of order and society wouldn’t necessarily turn into the Hobbesian free-for-all depicted in most games and movies. For people who live on the northern edge of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains, for whom the Arctic Circle is almost as near a neighbor as the United States, the most likely enemy is always nature. Where a gallon fuel oil can mean the difference between life and death, where the nearest major hospital might be a long helicopter flight away, survival is more about counting calories than ammunition.

“A survival sim is about resource management,” Van Lierop says. “I was really inspired reading about some of the Antarctic expeditions. These guys would very carefully plan out how many calories of food they are going to take in, versus how much they are going to expend. I read about how badly some of these things turned out because they made bad choices, or didn’t calculate things properly. When you hear about the Scott expedition, you hear about how they calculated they were burning 4000 calories per person per day. It was only after [they set out] that they realized they were burning closer to 7000, because they were pulling their sledge of supplies. So gradually they were all starving to death. They just didn’t know it.”

Knowledge will play a key role in The Long Dark. This is not going to be a game where you just wander around and peer inside a trash can and find an entire meal waiting for you along with fuel for your car. Nor will an abandoned cache wait for you to come find it. Other people are trying to survive, and the world’s already vanishing resources will diminish further as time goes by.

Van Lierop explains, “As players encounter other survivors, or encampments or find cabins etc., when they find knowledge of some sort — could be a map, a conversation with someone that tells you about something in the world — that knowledge decays. For example I might find a survivor on the road, and I have an interaction with him. They mention ‘Oh hey, two hills over there at the abandoned gas station there’s a car over there with some abandoned stuff’. Now that you have that on your map and that it exists in the world and a pretty strong sense that if you can get there quickly enough, you’ll be able to find it. But if you dilly-dally and get distracted by other stuff, it might already be gone. So there’s that constant push and pull between wanting to explore the world, having to think about how much it’s costing you to do that… It’s really a tug of war between exploring and staying alive.”

Exploring will require a measure of woodcraft. Van Lierop talks about how he wants players in The Long Dark to become hyper-aware of their surroundings. To be able to trace a stream stream to its source. To know how to escape predators, and the times of day when they’ll be most active.

Occasionally, those predators may be human, but Van Lierop stresses that combat and battles with other survivors are not what The Long Dark is about. In fact, originally they didn’t want to have combat at all, but eventually the team felt it was too artificial a limitation. Instead, The Long Dark treats combat as a last resort and, in most important ways, a failure. Every encounter with another character is a negotiation, an attempt to figure out if it will end in cooperation, indifference, or violence.

“It’s not about pulling your gun out before them, but trying to suss out what they’re looking for and if there’s a way they can help you, or them, are they going to try and kill you and take your stuff, are they in trouble and do they have anything you need that can be exchanged? We’ve been thinking about other survivors more as people and a resource for knowledge as opposed to just people who you kill and take all their shit,” Van Lierop adds.

Project Management

Right now The Long Dark is not quite halfway funded on Kickstarter. Hinterland are asking for $200,000 Canadian dollars, though it sounds like the Kickstarter money is more aimed at giving Hinterland an extra layer of spit-and-polish rather than funding the entire development.

“We’re kind of scoping when it comes to the content side, but even with our Kickstarter we’ve been really upfront with our backers, saying our goals are not built around adding more content to the game,” van Lierop says. “What we don’t want to do is end up in one of those situations where we we’re forced to have a bigger game, where we’d need a bigger team which brings more risk, etc. Our stretch goals are more built around things like making 30 minutes of custom music into 60 minutes. So it’s not stuff that risks the production of the game, but just adds more quality to the game. So that’s where we’re kinda at; we have a good sense of what we can build.”

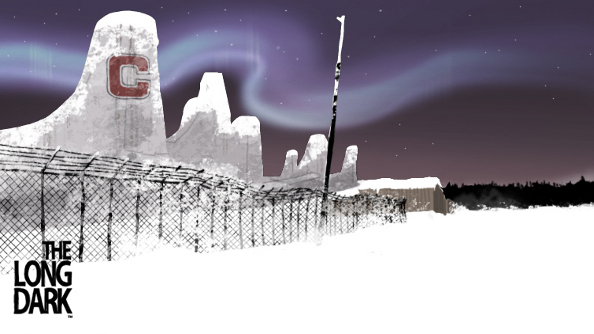

While The Long Dark will be a realistic and sophisticated survival sim, its presentation will be far more abstracted and stylized. “

Van Lierop explains, “We’re not going to chase photo realism, it’s not a goal we care that much about. …Hokyo [Lim] was the art director of League of Legends and the Unfinished Swan, and so Hokyo has a strong sense of his own style, and that’s why I wanted him to work on this, because I knew It needed a very unique art style and iconic identity for the game. So the style that you saw in the concept we made is what we want the game to look like.”

With a strong team of veterans developers, including former Volition technical director Alan Lawrence, Hinterland are well-equipped to deliver on their ambition to create a stylish Canadian STALKER. It’s especially encouraging to hear van Lierop talk about how much he wants to avoid experience and perk systems that create an illusion of mastery, and create a game with enough depth to give players the real thing. As much as The Long Dark might be a story of man versus nature, survival depends on becoming attuned to that dangerous, hostile environment.

“We will be successful,” van Lierop says, “if we can deliver that kind of an experience to the player. Where they not only feel immersed in how beautiful the world is, but where their time in the world makes them better at being in the world.”