When I finally met Jim Rossignol at GDC to talk about Sir, You Are Being Hunted, I mentioned how difficult it had been to find him inside a crowded Starbucks. The only picture I had of him was his Twitter profile picture… which is a shot of Patrick McGoohan in The Prisoner. Rossignol, it turns out, does not look very much like Britain’s coolest secret agent and inmate.

Rossignol laughed, but he was off to the races as he explained what The Prisoner meant to him, and why it has endured as a seminal work of British television. In both of his careers as a game journalist and developer, Rossignol has been trying to protect and promote the same values that created some of the UK’s most memorable characters and cultish success stories.

It’s not easy. In both television and games, the trend is toward glossier, less personal works. “The formula’s been sweetened and it’s less weird. That smooths out some of the bumps to consumption, but it’s smoothed out some of the influence,” Rossignol said. “Because it’s the stuff that’s really weird that kind of pushes people off into a new direction.”

Rossignol was pushed in a new direction by odd TV and odd games for most of his adult life. Now he’s tried to return the favor.

The Prisoner is a quintessential blend of the high-mindedness and camp weirdness that defined British TV in the 1970s. One of the show’s most terrifying antagonists is a cross between a water balloon and a beach ball. In terms of unlikely menace, it rivals Dr. Who’s shop-vac Daleks.

This is the model and the moment that inspires Rossignol, even if it may never return for mainstream British culture.

“American TV is so successful, and the model so potent, it’s pretty much swayed the needle for everything. I don’t think we’ll ever get back to the low-fi weirdness that 60s and 70s British TV had. Especially in the sense of threat that they had,” Rossignol said.

Rossignol first saw The Prisoner when he started writing about games. That era of British TV was already a memory, and UK dramas were increasingly a cultural export aimed at a broader, more Americanized global audience.

Games have followed a similar arc. If the 1990s were home to an explosion of creativity, variety, and possibility, the 2000s were increasingly about refinement, polish, and mass appeal. It’s no wonder that PC gaming itself seemed almost to be teetering early in the PS3 / 360 era. Its most successful ideas and developers were moving over to consoles, and ambition and creative daring were increasingly supplanted by a focus on mass appeal and high production values.

The raw and the weird suddenly needed champions, and that’s why Rossignol and his colleagues founded Rock Paper Shotgun.

RPS was a PC gaming blog, but it’s always been defined by the idiosyncratic relationships its writers have with the term “PC gaming”. By stepping out of the mainstream, away from bland cover stories and lackluster ports of blockbusters designed for other people, Rossignol built a place where he and other writers could champion the weird and unique. Early RPS history is full of enthusiasm for janky, post-Soviet gaming like STALKER and the Men of War series.

While building RPS and publishing a book marked major milestones for Rossignol, they also left him with an increasing dilemma.

“In game journalism terms, I’m starting to get on a bit now. I’m 36. It’s that kind of age you start thinking about what else you could do. I’ve done everything, in terms of my original goals. …I’ve done what I set out to do,” he admitted.

Yet the hunger for those out-of-left-field experiences was still there.“I spent years writing about games and saying, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if…?’ But I kind of reached the point where, with certain games, I’ve realized I’m going to have to make them [myself] if I want to play them at all.”

Ironically, Rossignol’s experience with RPS had already prepared him for his transition out of journalism.

“Suddenly at that point I wasn’t just getting work in from editors and then doing it as best I could and then moving onto the next thing,” he said. “That was the point at which my experience changed from focusing on writing to focusing more on project management. Shifting over from project management to running a game development project wasn’t too big of a leap.”

If founding RPS made Rossignol the kind of responsible manager who ensured that all the “i’s” were dotted and all the “t’s” were crossed, then EVE helped make him executive material.

“Running large corporations in EVE… kind of prepared me for some real world business in a way. Because a lot of that was sort of managing people’s expectations and trying to keep things regular and make sure that everyone was having a good time. And in a way, that’s how you run a business.”

In Big Robot, Rossignol has found a small group of collaborators who share some of his particular manias, and have a few complementary obsessions of their own. It is a studio that prizes systems above all. One of Rossignol’s favorite series is STALKER, a particularly unforgiving and sim-like survival shooter, while for his design partner, James Carrey, ArmA is an important touchstone. Both series are renowned for their complexity and emergent gameplay… and for their lack of polish. But that’s part of what draws Rossignol to games.

“I think [elegant simplicity] has become a really strong philosophy in US game design. To sort of avoid messiness, to smooth over that stuff as much as possible. Which I think comes in part from the success of Blizzard, who just design things that are polished to absurdity,” Rossignol said. “They’re always these beautiful, super ultra-playable games. And yet. Something is missing there. And I think that messiness is super valuable.

“There’s something ‘European vs. American,’” Rossignol said. “You look at the Creative Assembly stuff: they’re always kind of messy and there are two sets of systems. The campaign map and the battles. And that’s more interesting to me, even if that’s not as ‘good’ a game design. I think that [American] design then perhaps then becomes almost puritanical. There’s something really rich about mess.

The games Rossignol cites are also known for their gleeful indifference to whether players can keep up with them. They are not afraid to challenge a player’s skills and patience. ArmA and STALKER are both games where one mistake, or even a misfortune, can be instantly fatal.

Sir, You Are Being Hunted takes its cues from that persistent sense of menace and frailty.

“What’s really exciting about games is vulnerability. There’s almost like two schools of thought on that. One is like, power fantasies are interesting because they’re fun to play and that’s thrilling. But also, the peril of playing the hunted is more interesting. The more dangerous it feels, the more vulnerable a player feels as they’re in the world, the more we feel we get out it,” Rossignol said.

Yet Rossignol wanted his menace to be leavened by a certain absurdism. He wanted the mixture of wryness and menace of early Dr. Who and The Prisoner.

“When we were designing the way the robots behave, we wanted you to be hiding in a bush laughing at the fact that they’re talking about the weather, but too afraid to stand up and be seen. Things can be funny and horrifying at the same time. That was the target for us.”

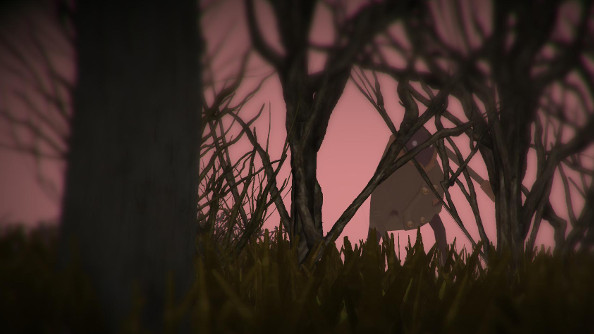

Sir, You Are Being Hunted is a fable about the alienness of the familiar. The things we take for granted every day, suddenly taken out of context. It is about the merciless fops we forget to notice, and the profound unnaturalness of the British landscape.

“James and I –James is my designer, James Carrey — We both find the British class system slightly threatening. The implacable, kind of untouchableness of the British aristocracy is a very weird thing. A very threatening thing in some ways,” Rossignol said, “I don’t think we had even realized that we were connecting to that when we were doing the caricatures, because it was just a funny, ‘Hey, Robots in Top Hats!’ kind of thing. And as it went on, we realized we were kind of expressing some of that …sense of threat.”

Britain’s eternal class of landed gentry are the antagonists of Sir, You Are Being Hunted: bluff, buffoonish, and laughably oblivious… until they suddenly turn on you. And then you realize that it’s you who is the fish out of water. The mecha-gentlemen have reasserted their rule, turning all the archetypal landscapes of Britain into a giant hunting ground. All that’s left of the people who once lived there is piles of bones and bourgeois artifacts that show allegiance to a society and a system that turned on them.

“I’m wearing my heart on my sleeve a little bit, it’s quite a crude metaphor: robots running the country,” he admitted. “But the other thing is that there’s a kind of — There’s a certain attitude of the super rich that is super alienating. And I think… certainly myself, and most British people encounter that sort of people, that is a really alienating experience. They all come from this other world. They all seem, if not threatening, then sort of disconcerting.”

The landscape amplifies that sense of alienness. On the one hand, Sir, You Are Being Hunted is very familiar. It’s resonant even if you’ve never set foot in the UK, and only know the country from films and books. Yet without people, it becomes as unsettling as any Gothic horror story. It might be down to the juxtaposition between humanity’s absence and the land’s deep connection to the people who’ve lived there over the past millennia.

“There isn’t a landscape in Britain that hasn’t basically been crafted by humans. Even places that seem really wild, like moors and highlands and so on? Those are places that have previously been cleared, deforested, previously been farmed. There isn’t anywhere in the Uk that hasn’t been changed by the fact that people have been living there,” Rossignol said. “I think we could have actually lost all the buildings and just kept the map and it would have been just as powerful.”

That landscape, and the way the AI hunts across it, is what makes Sir feel more complicated and its enemies feel more implacable than traditional stealth games.

“It’s a very noisy environment, because it’s an open world and landscape and there’s an incredible amount of detail and scenery and material. It’s a very different sort of playing field than, say, stealth games that are in corridors and warehouses that have very clearly defined values. …The nature of the kind of environment we try to create means the AI interactions are going to be more complex,” Rossignol said.

Having so many variables and actors in the system makes Sir a bit more difficult thanks to its unpredictability. It also catches players out when they attempt to game it the way they’re used to doing in other games.

“There is so much going on: there are so many entities, and those entities have so many variable which could throw them off. It becomes a really complicated, chaotic system. Which in some ways I think is perhaps challenging for players. I think players might [prefer] a system they can discern. But at the same time, the vulnerability and rolling crises people get from it is really well fleshed-out. I’m really pleased with how the main hunter AI works.”

Rossignol smiled. “We’ve been watching people play, and we see them run around behind a wall and crouch down thinking the robots will lose them. Of course, the robot has seen them crouch down, and it’ll run around to see if they are still there. Players don’t expect that level of activity from the AI. And that kind of excites me in a way. Because it’s kind of pushing back against this tendency where game AI is there to let you win. It’s dumb. Not in this instance, and I quite like that.”

With Sir, You Are Being Hunted finally hitting its official release, Rossignol and Big Robot are free to consider their next move. Looking around at what inspires them, their tastes haven’t really changed. They like systems and freedom, not authored narratives. So they like RPGs, but would prefer to do a roguelike. They like space games, but Elite is the one they identify with the most. They are waiting for the inspiration behind their next system.

Rossignol sounds like he he wants to make players run for their lives at least one more.

“I would like to do a game where we create just a single vast landscape without doing shards. Where it would not be a hide-and-seek, run back and forth kind of thing, but simply a huge journey where there’s something terrible behind you and you have to run. To do something that like that would be great. Certainly, in the back of my mind, I know that might be an even stronger concept.”

Sir, You Are Being Hunted is available now.