Between them, Brenda and John Romero have helped reshape the videogame industry landscape many times, and they continue to innovate today. We spoke to the development veterans at this year’s Develop conference – in part one of our chat we discussed the state of modern first-person shooters, and why Romero Games is their most important studio yet. In part two, we tackle diversity in the industry, the dangers of career burn-out, and why outsiders thrive in the development scene.

Doom fan? Of course you are. Why not check out our list of the best shooters on PC?

Brenda, you grew up playing with incomplete board games and making up your own rules – has that given you a natural affiliation with modding, and tinkering with the components of videogames?

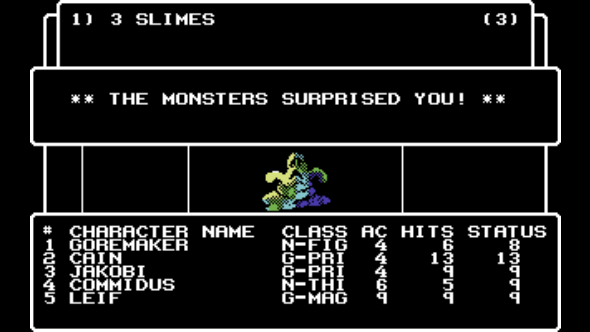

Brenda Romero: No. Wow, why didn’t that happen? Really early on, I got the Wizardry editor. John and I followed different paths: he’s like ‘I need something better to make cooler games’ and I’m like ‘Holy shit, the Wizardry editor, wooo!’ I learned enough code to be functional, but it was all in languages nobody needed to be functional in.

I took a couple classes in assembly, but taking a couple classes in assembly is like taking a lecture on surgery or something. It’s funny, now that you mention it, but I’ve never wanted to be involved in modding.

During your talk, you mentioned the five-year average before devs burn out in the industry. What do you think needs to change to raise that average?

BR: On the one hand, I would say expectations. I don’t know what people think it’s like to make games. A lot of those people who do leave in those five years might not understand quite how difficult it is.

In my slides I talked about climbing the mountain – are you going to do a steep climb or a [shallower] climb? Most people who ‘get there’ are steep climbers, and they’ve been doing it since they were a kid like John and I… But it depends on what you’re working on. If you’re working on something that you love, time goes [fast]. What are you really passionate about? If you’re passionate about playing games, it’s very different from being passionate about making games. Do you want to play the game or do you want to make the game?

You also talked about the game industry being made up of outsiders. Do you worry that gaming’s progression beyond a niche hobby endangers the ‘outsider’ sentiment that catalysed the scene and the creativity within it?

BR: Games are certainly mainstream. But I still think we’re attracting the weird ones, the outsiders. I talked to some guy today and you could tell that he didn’t feel comfortable talking. I recognised myselfin that.

He saw in me someone who’s been talking to game developers for 36 years. But if you saw me eight years ago when I met [Raster Blaster creator] Bill Budge… He is one of the gods of the industry. Bill was outside this restaurant I was in, and I stood up and applauded.

If you were dining in this restaurant, you would have seen – with no idea why this was happening – a woman standing up, her chair tipping over, apparently applauding nothing. [Working in the industry] takes a unique person. We were always creating something interesting, something cool, something other people couldn’t see. Games are perfect for that.

And there are people who will find even greater escape in making games for others – that’s just a profound and beautiful type of control. I don’t mean that to sound like a paradox: being the puppet master is incredibly powerful. I don’t think [that attraction has] changed that much. I don’t know of any game developer that I’d think, ‘Oh yeah, that dude? He was the most popular kid in school’.

John, in your talk you spoke about how proud you are of your heritage. Why do you think we don’t we see more high-profile game developers from diverse backgrounds?

JR: I got really lucky. People that are disadvantaged don’t know what they’re missing a lot of the time. They don’t have access to what’s out there, and if they don’t know it exists, then it’s hard to even get there. So education is where it’s at – in school, push them towards STEM, get them out there.

BR: Where we lived in California, if we drove 45 minutes in one direction, we would have been in the middle of some of the wealthiest homes in the state. If we drove 30 minutes in the other direction, we were among many of the poorest Mexicans in the state. Most of them were day labourers for farms.

High schools are always looking for people to talk, and the place John would speak at, without fail, would be [the latter]. My niece is a teacher at [a high school that’s]… I guess we’ll say it’s the last stop, on the last block. You have to get kicked out of three schools just to get to her school. Her students are heroin addicts, meth-heads… some of them have prison records. And she loves them.

She educates them, and she has them for four years, and John speaks to her class pretty frequently. I think the industry is a hell of a lot more diverse than it used to be, but it’s about making sure that people have access. Recently, John and I worked to get a grant for a specific school so they could change their entire computer lab and get new computers, and that’s something we’ll keep doing.

Top image credit: Joe Brady