Like many successful indie games, Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes – an asymmetric co-op game where one VR-wearing friend tries to defuse a bomb while their friends talk them through it – began life as a Global Game Jam project. After the Game Jam, the developers put a video of the game online, and when it reached 100,000 views they knew they were onto something. So naturally they quit their jobs and devoted two years of their lives to this niche VR project with seemingly big appeal.

You know what else has big appeal? The games in our picks of PC’s best games.

Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes was first released on Gear VR in June 2015, followed by the PC version which launched in October of the same year, itself followed shortly by Mac. It has done very well in that short time.

“We’ve never actually revealed any sales numbers properly,” says Steel Crate Games’ Ben Kane at GDC 2016, “but now that we’re on [a selection of] platforms and different stores, I’m happy to say that in total – aggregate – we’ve sold more than 200,000 copies.” Not bad for a small team taking a gamble on a game based around expensive new tech.

Because VR owners were difficult to come by, the developers toured around shows for feedback for an entire year, shoving the game in people’s faces – quite literally, by strapping it to their heads. This was an exercise in shaping and refining based on player reaction and feedback. The idea was to give players a memorable time, but the developers also devised a way of having players take those memories with them, along with some marketing materials.

“We didn’t run our demos like arcades,” explains Kane. “This wasn’t something where you just come up and play the game and then left. We wanted it to be a memorable experience when people play our game, but also a useful tool for us, and to do that we had a really structured routine. Part of this was necessity, because we were doing VR, and with VR you have to clean the headset, put it on their head and adjust the straps. But even if we weren’t doing VR, I would still use this sort of process.

“This is how it works: when a couple of players came up to play our game, we would give them a postcard, and this postcard had everything that we wished they wanted to know about our game. So things like the name of our game and where to follow us on Twitter. But on the other side there was information that they filled out themselves, so as we explain the rules of the game to them they would write their names down as the defuser, or as experts, then they’d tick a couple of boxes for what kind of game mode they’d play.

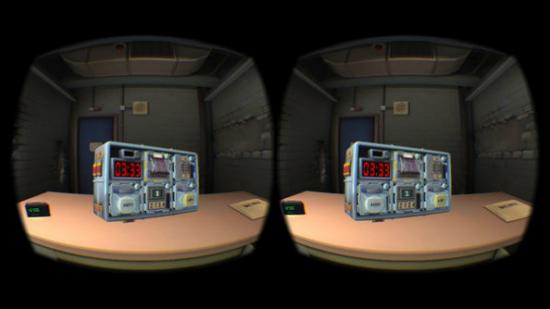

“Then, as they started playing their game, the experts would start scribbling down all these arcane symbols, anything the defuser was yelling, and they’d try sketch pictures of the bomb – just creating their story. At the end of it, very ceremoniously, I’d give them a big stamp for exploded or diffused. It was a souvenir for their personal lives and it was something they would want to keep. And if they had a really stressful time playing our game, they might not remember anything, but now they have this evidence that they could use to tell the story to their friends.”

It’s savvy decisions like this that helped the game hit that impressive sales figure. It wasn’t just in how the game was presented, though, as this eye for clever design also fed into the game, making sure it felt different if played more than once. For example, the VR player will sometimes face distraction techniques like power cuts. This isn’t random – it’s based on a calculated score, which itself is based on how many puzzles you’ve solved, what time is left, and some other parameters.

If you’re doing well, the game will attempt to scupper your efforts – setting off an alarm, tripping the lights and doing the best it can to put you off. On the flip side, it’s designed to not kick you while you’re down, so these events won’t trigger if you’re doing terribly. It’s not just about being fair – it’s a way of making sure the bomb is as close to exploding as possible, making it exciting for the players. The music works in harmony with this, growing in intensity until it hits something the developers call “the death bell” in the final 30 seconds.

This layer of unpredictability also carries across to the experts who are talking their friend through the bomb’s defusal. The rules that govern the game and the manual the experts are reading are also procedurally generated. This, Kane says, is the game’s “secret sauce”.

With so much going on behind the scenes, it’s no accident Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes has already done so well. Once VR becomes a bit more mainstream, its popularity can only soar, and it’s these rules and random elements fueling the game that will keep it fresh through repeated plays. It seems like the perfect VR game, so it’s good to hear it’s been a success.Our Phil spent some time with Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes and he reckons it’s the best VR game available right now. Hopefully this a sign of things to come with the tech.