In a constant scramble for votes and top one hundred placement, the most important question an independent developer can ask is how exactly they can beat on against the current and get their game greenlit, how they can reach out towards the Greenlight that ever recedes before them as, every day, more games accrue more votes. And what can Valve do in response to the needs of these indies, to make the experience easier, fairer and more agreeable?

A year’s worth of criticism and analysis from the indie community has produced its fair share of insight, analysis and frustration.

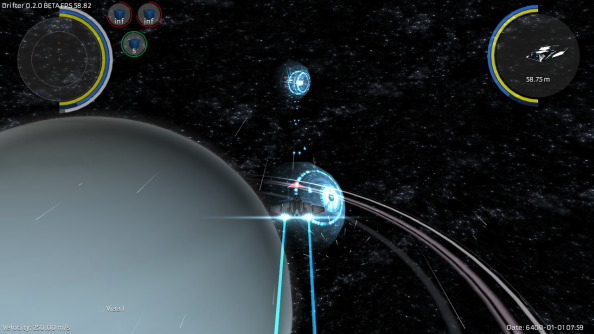

“It’s probably a lot more difficult to get to where you need to be on Greenlight than most people realize,” says Colin Walsh, who’s game, Drifter, is gunning for a place in the coveted top one hundred. Hoping that perhaps 3,000 yes votes might be enough to get him noticed, he soon realised that he needed voting numbers more than five times that. He estimates that more than 16,000 yes votes are needed to climb that high, but he says that’s only the start of a far greater journey.

Valve typically approve less than a dozen titles in each batch, though the recent anniversary Greenlighting of one hundred new games, followed by another 30 this week, is a stark exception to this. It’s not likely to become a trend, though, so the best way to get Valve’s attention is still to grab a spot among the top twenty or top ten games. How many votes does that need? “By my estimates a game is going to require somewhere around 50,000 yes votes to get into the Top 10,” Walsh calculated, in an extensive blog post for Gamasutra back in July.

And those votes are only the yes votes. If only half those who visit your Greenlight page give you a yes vote, that means you need to point 100,000 different Steam users to your page and gaining that much traffic, particularly for a small indie, is a Herculean effort, even if it’s one Walsh describes as “straightforward.”

“There’s enough information given to give you a good idea of how well your game is doing relative to others,” he says, “as well as give you an idea how other games currently doing quite well have performed historically in the same timeframe as your game. That way you can figure out if you’re being effective in bringing people to your Greenlight page. You’re also given a lot of tools to inform visitors about your game and to help you engage with and build a potential fan base, which can be used to improve your chances of getting greenlit.”

Certainly, driving traffic to your Greenlight page is critical and it’s obvious that votes are the currency with which success is bought. But Greenlight is barely visible to casual Steam users. It’s not displayed very prominently in either the client or on the Steam homepage, nor are users given any incentive to navigate to it or through it. To the average user, it’s somewhere between a footnote and an insignificance. That suggests, of course, that Valve need to place greater emphasis on Greenlight, but also that many or most greenlit games succeeded because of serious, targeted campaigns that took a lot of work.

This was the case for Broforce, which won over 82,000 yes votes after a very busy Greenlight campaign. Shaz, of developer Free Lives, says the team were constantly engaged with a growing audience and that this, in turn helped them to promote the game. “Keep active, keep updating and use social networks to drive traffic to your Greenlight page,” he suggests. “We tried to keep things fun and humourous, like asking people to vote for us on Greenlight ‘or let the terrorists win.’ We had links to Greenlight on our trailers, website and Facebook page, and always asked interviewers if they wouldn’t mind including it in their articles/reviews.”

And while Facebook and Twitter might be the social media we immediately think of, Shaz adds that YouTube users playing your game could also have a huge impact on driving traffic your way:“They are an invaluable resource to indies,” he says. “We’ve found that most Youtube reviewers are awesome guys happy to engage with you if you make the effort to reach out to them. Having a game that works well in Let’s Play formats helped us tremendously in getting extra coverage.”

Shaz’s colleague Ruan also blogged about the Greenlight experience, sharing graphs and statistics that show spikes when new features and YouTube videos were released. The blog entry served both as a rebuttal to several key criticisms of Greenlight, such as the accusation that it marginalised niche games, and documented the growth of a game that was initially entirely unknown.

Ian Hardingham of Mode 7 Games, whose Frozen Endzone was recently greenlit, says he found Greenlight’s statistical breakdown very helpful in terms of gauging not only visitors, but what those visitors responded to. He suggests that developers experiment during their campaign and see it as a chance to gain valuable feedback on what’s working, both in their campaign and in their game.

“Use it as a test-bed,” he says. “Change things around and see how people react. Work out what kind of PR gets you the most hits. Work out which bits of your game people don’t like, and try to find out why. Maybe you want to make a controversial or disruptive game, but this information is still very useful. Maybe you want to make a horror game and you find that what’s really making people throw up is your control scheme! Information is good.”

At first, he was speaking about Steam as a whole, about what would be a fundamental change to the way the entire platform works, but then he drilled down to specifics on Greenlight and may have foretold its end. “We came to the conclusion pretty quickly that we could just do away with Greenlight,” he said “That it was a bottleneck rather than a way for people to communicate choice.”

Tearing it down may be the long term plan, then, but there’s no timescale for when that’s going to happen and Newell’s words are already more than six months old. Still, Valve won’t commit to the service in perpetuity. Developer Alden Kroll told us that, “Right now [Greenlight] is helping us gather very useful data on titles that want to be on Steam, but that role might change over time.”

For now, indies must cross their fingers, but it’s also worth considering this advice from Sos Sosowski, creator of McPixel, the first Greenlight game to see release.

![]()

“I found it much easier to handle Greenlight due to having an already released game out there,” he says. “So my advice is, release your game before going into Greenlight!”

There is another implicit point to Sosowski’s words. With all this drive to get greenlit, it might be hard to recall a time before the service even existed, but it is worth remembering that success still exists outside of Steam. Indie games can still achieve an audience without Valve, be those games McPixel or Minecraft. Greenlight is a process with an entry fee, with no guarantees, which presents many uncertainties and, with each passing day, grows ever thicker with competition. Rather than putting all their efforts into chasing votes or into second-guessing an approval criteria, indies could simply do what it is that indies have always done: go their own way.