In utilitarianism, the rather cold ethical theory that suggests all action be directed towards achieving the greatest good for the greatest number of people, there’s a hypothetical lifeboat scenario. The boat will sink unless a few passengers step out of it into the ocean. Do you shove the doctor, who may go on to save more lives? Or the famous artist, who contributes to happiness on a global scale?

In Overland, the boat is a car. But the cold maths is complicated somewhat. What if the famous artist is instead, like, a really cute dog?

At least one of the best indie games on PC is about saving pugs. Play it, if you haven’t.

“Mathematically, dogs in Overland are inferior players,” says designer Adam Saltsman. “They don’t have opposable thumbs, so there’s a whole bunch of game actions that are ruled off for them. They can’t drive cars. Their use of inventory items is very limited. [But] people will in a heartbeat abandon a human to save a dog.”

In Overland, a road trip in which you lead an evolving band of survivors through a ruined North America, you scour randomly generated turn-based maps for supplies to keep going and protect yourself against the strange, sound-sensitive creatures that have settled in the US. The cataclysmic event that changed Earth forever isn’t explicitly addressed – but it’s left humanity (and its pets) prey to strange, spiked monsters with angular, insectoid legs.

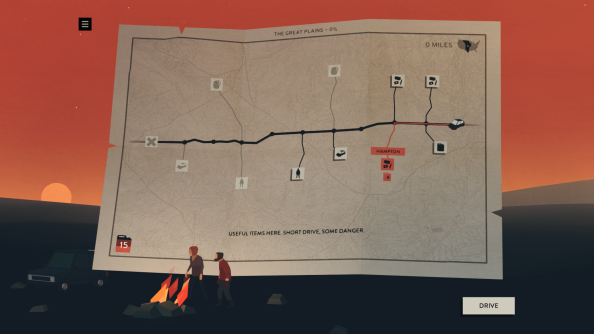

Outside of these encounters there are ‘interludes’, where you’ll pick a route – perhaps taking a detour for resources, or betting on there being a medkit for your wounded specialist at the next stop.

“There’s no saving the world,” Saltsman warns. “There’s no mission of redemption. There’s no adaptation, no climbing in a rocket and starting a moonbase. It’s just sort of over and this is your shot, your last two weeks.”

The traits of your passengers are randomly generated, too. Once you know that a dog is six-years-old and has attitude, it becomes somewhat harder to leave it by the highway and drive on.

“There’s this irrational, illogical attachment that people develop or project that I think is really cool,” muses Saltsman. “Where the game is now, I think we’ve only done about ten percent of what I want to do with that stuff. But I really like it.”

Saltsman is an unusual interviewee. He has a habit of digging into the failings of Overland, a game he hasn’t yet released, as if he’s not on the line to sell his ideas but instead deliver a premature postmortem.

Perhaps that shouldn’t come as a surprise: this is a developer who advocates being your “own first critic”, and who has garnered 27.1K followers on Twitter by providing a welcome upfront perspective on game design – chatting openly about what works and what doesn’t.

Saltsman’s past successes have been characterised by extreme simplicity and immediacy: the one-button score-chasing of the archetypical endless runner, Canabalt, or the abstract spatial puzzling of the game he made with Greg Wohlwend, Hundreds.

“There are throughlines there,” he says. “I’ve made at least two games that are about a vague end of the world – that’s a thing that I enjoy. You get to imagine it along with the author or game maker.”

But how does that stripped-back sensibility translate to XCOM-style turn-based tactics – a genre Saltsman has only previously explored in unreleased prototypes?

“I’m interested in making something that has, like in Go or Chess, this notion that you can make one small move that has implications in the short term and large, unpredictable consequences in the long term,” he says. “But to embed those things in a more approachable format that’s experienced in ways that are more analogous to a board game or a book or movie.”

Overland bears what Saltsman calls a “thin interface”: a simple premise, controls with a short learning curve, and a reliance on aesthetics and audio over UI to communicate what’s happening. It’s a far cry from the fiddliness often associated with strategy games. Yet Overland’s two layers of tactical decision-making clearly recall XCOM, while its pacing and vibe is indebted to the board game Pandemic.

“I was terrified I was really, really bad at [designing turn-based games],” remembers Saltsman. “I don’t know if I’m any good at it now. I think I’m just good at designing Overland, but I’ve been practicing that for a long time.”

Just as Overland has become familiar to Saltsman, there’s a certain recognisability there for players too.

“For people who have visited or live in the US there’s a raw sense of, not exactly comfort, but maybe nostalgia,” says Saltsman. “We tried to make the decisions reminiscent of the process of standing around in a gas station parking lot before there were iPhones, looking at an atlas, deciding where to get lunch today and what hotel to stay in tonight. The daily stress.”

As much as Overland is a utilitarian simulation of a doomed future, it’s also an old-fashioned American road trip. One in which man’s best friend leans out of the passenger window to catch the breeze.