Our Verdict

A lumbering historical murder mystery with little regard for tension or pacing, but one that packs in such dense detail you can’t help but respect it. Pentiment immerses you in 1500s Bavaria and that’s the main event.

In his 1977 play Abigail’s Party, writer-director Mike Leigh grounds you in the minutiae of a suburban dinner party in such pedestrian, tedious detail that by the time something truly dramatic happens – a fatal heart attack – you’re shocked out of a stupor. The stakes were so low, for so long, that the play had started to feel like your own uneventful life. And now something absolutely massive’s happened. And it hits you accordingly. Our Pentiment review finds a similar situation in Obsidian’s latest.

If Mike Leigh was the master of the kitchen sink drama, then consider Obsidian the purveyor of the scriptorium whodunit. This is a murder mystery told at something between walking pace and the movement of tectonic plates, a story that could care less about keeping you entertained as long as you understand the precise details of life in a German village in the 1500s, the social hierarchy within it, and its relation to the church.

It takes quite a while, then, before there’s any murder. Or indeed, any mystery. Instead, the first few hours of Pentiment are spent acclimitasing to existence in the Holy Roman Empire. Hero Andreas is staying with some farmers in the village near the Abbey where he’s been commissioned to create artwork for a text. In my game, he’s a skilled orator of Italian descent with a hedonistic bent, a logical mind and half a medicine degree. In yours, he’ll have an entirely different backstory and accompanying skills depending on your decisions. It’s not Wildermyth, but there’s at least some player input during what are otherwise pretty linear opening hours.

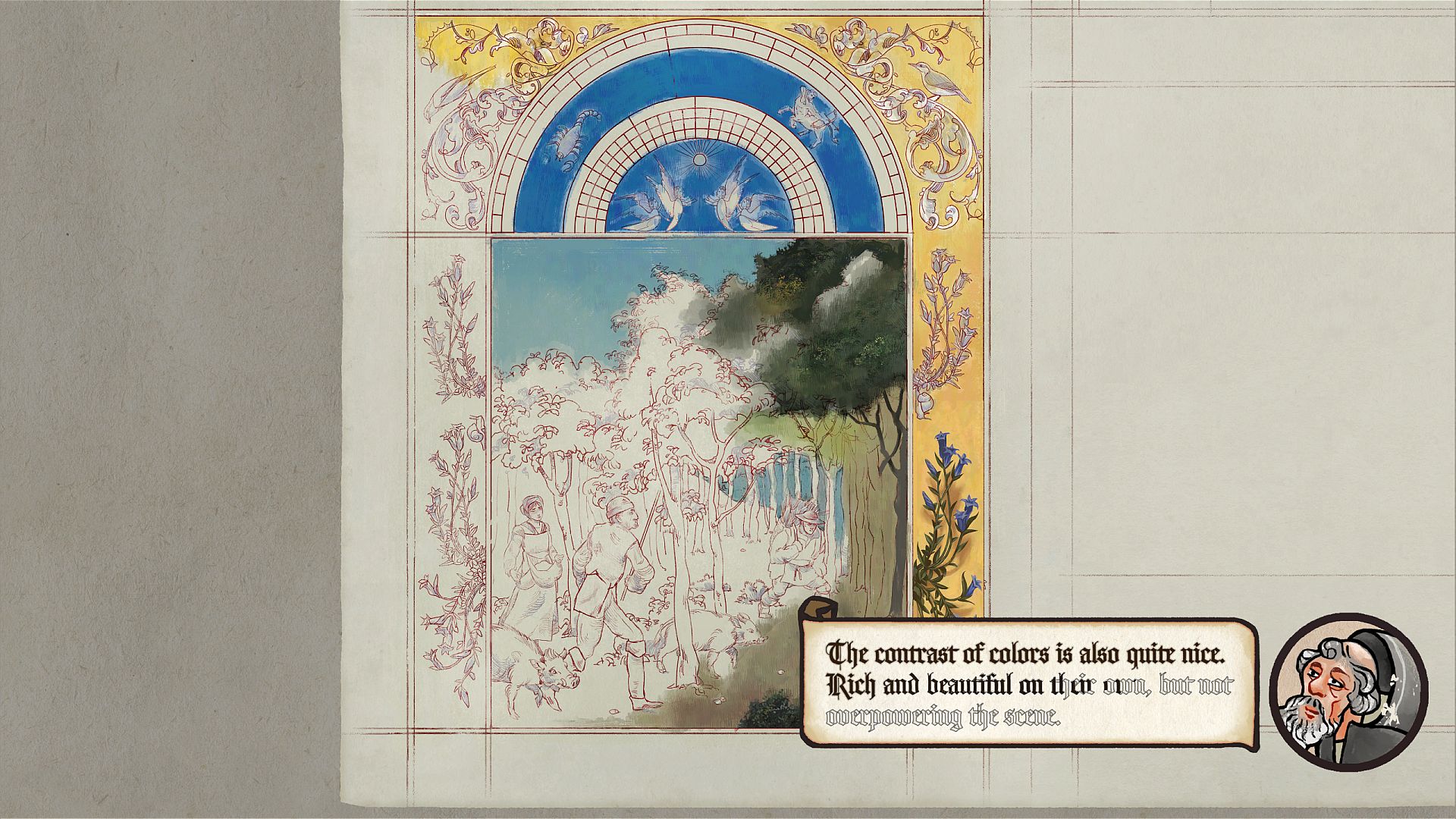

The presentation’s striking. It’s Kingdom Come: Deliverance, expressed as a 2D point-and-click. It’s an interactive novel whose calligraphy is being penned right in the moment you’re experiencing it, and whose quill strokes imply tone of voice, social standing, time and place. You’ll get pretty tired of the sound of nib on paper by the end, but never have typefaces worked so hard to convey character and class. The art style falls somewhere between medieval tapestry and webcomic, and the conceit behind the UI is that you’re seeing it all as pages in a book.

As you move from one screen to the next, traversing your village, some cosmic librarian flips the page and a new scene emerges. Some names and places are underlined in dialogue, and when you click on them you’re met by an alarming long finger pointing to that word and then, as the camera zooms out further from the page, a little glossary definition in the margin. Your map and journal live in this same book, and while it makes for some clunky navigation, it is at least thematically consistent.

There’s something compelling and even comforting about the Persona-style schedule to each day. Getting used to the rhythms of life in 16th century Bavaria really grounds you in the village of Tassing. You feel like you’re living a life there, waking up in the Gernter’s farmhouse, heading up to the Abbey’s scriptorium to work on your art, stopping for lunch at a number of destinations, back to work, then heading down through the meadow from the abbey to the village by sunset and making any further social calls before vespers and bedtime. It’s a routine that teaches you a little history, and imbues a little extra immersion, all at once. Unlike Persona though, time only moves forward after you’ve completed certain actions, so it’s less about figuring out how to spend your time and more about identifying the box (or boxes) you need to tick to begin the next phase of the day.

Meal times are a big deal here. They’re a regular fixture on your daily schedule, and you’re usually free to break bread with one of several households throughout the village. Sometimes there’s nothing much to come out of it, other than a bit of backstory and bonhomie. At other times you might get a crucial morsel of information with your fresh pottage and quail.

Mostly, though, you work. In Act One, Andreas works in the abbey’s scriptorium, where monks illustrate religious works commissioned by high-ranking church officials and nobility. We’re barely a few decades from the invention of the printing press at the beginning of the story, and Pentiment shows you precisely how important these newfangled things are in this society. In certain circumstances, they might even become a matter of life and death.

And eventually they do. Like Abigail’s party, by the time blood’s spilled, it feels all the more impactful because everything else you’ve been experiencing has been so ordinary. Quarrels in the scriptorium over Brother Pietro’s work rate. Dinners in farmhouses, rye bread and sheep’s cheese and gossip about nuns. A heavy rain and a damaged wall. Then: murder.

It’s only at this point that you have any meaningful input to Pentiment. In this first murder investigation, your actions and decisions start to carry obvious weight. You’re running around the village like Columbo in a tunic, gathering clues, untangling the tittle-tattle from salient facts. And the things you uncover – or don’t – have a real impact on the conclusion of the case when the Archdeacon and his men come to town. This, finally, is life and death stuff.

This is a pattern that repeats through Andreas’ life, which is told alternately in microscopic detail through that daily routine, and in sweeping skips through time after which you, the player, are left to discover what Andreas has been doing in the interim via conversations in the present. He’s a true renaissance man. Artist, yes, hedonist and raconteur, possibly, and amateur sleuth to boot.

The payoffs, if that’s the right word given the grim subject matter, arrive at the conclusion of your murder investigation. It’s here that all your choices, the information you gathered and how you interpreted it, sends the story spinning off in one of multiple directions, and as time lurches forwards at disconcerting pace, you’re shown the implications of everything you said and did.

And so mechanically and systemically, Pentiment’s pretty watertight. The crime investigation elements aren’t robust enough to rival BigBen’s Sherlock Holmes games, but they’re a means to a seismic narrative end. Your conversations spill over with historical research and political insight, to the extent that you could probably present a semi-convincing position on Lutheranism in the real world if it ever happened to come up.

But what bothers me is the pacing. Is it all a deliberate design philosophy to slow the journey down to such a rate that the player’s soaking up every morsel of historical accuracy, appreciating that the typeface in which each character ‘speaks’ reflects their social standing? Or – and I think you can tell I suspect it’s this instead – is it an accidental byproduct of its well-meaning but clunky picturebook presentation?

There’s a moment where you have to pick up some sticks for a local widow at one point, and the way Andreas leans down to get them, it’s like Pentiment’s getting paid by the hour. Everything you do seems to take longer than you’d hoped, from getting through the reams of script involved in each conversation to navigating from one side of the village to another.

The thing is, as humans we’re hardwired to invest more emotionally as we invest more of our time. Stories we spend a long time with seem to become inherently more epic, whether or not we’re especially impressed by the specific events. As frustrating Hungarian filmmaker Bela Tarr puts it: “I despise stories, as they mislead people into believing that something has happened. In fact, nothing really happens as we flee from one condition to another … All that remains is time. This is probably the only thing that’s still genuine – time itself; the years, days, hours, minutes, and seconds.”

As much as it’s about history and murder mystery, Pentiment’s mostly a game about time. The ambitions and dreams you have as a young man, and how easily they can be derailed. Your relationships and their fragility. How familiar surroundings can change dramatically due to the most happenstance events. In the end, whatever character you choose and whatever choices you make, however frustrated you become by the lumbering pace… you end up lamenting lost time, wishing you could go back and do things differently.

For a not insignificant portion of my time with it, I wondered if I’d be giving Pentiment the benefit of the doubt to this extent if it wasn’t made by Obsidian. The answer is that probably I wouldn’t, and that ironically I’d probably have given up on it just before the legendary RPG studio’s qualities really come to the fore. Truthfully the art style doesn’t hit my eye in a way I find particularly pleasant, but the craft on show for how well it immerses you with the concerns and motivations of a small group of villagers, nobles, and bible bashers is classic Obsidian.

The writing can be inconsistent in its tone, swinging from the formal conventions of olde English to very American modern parlance like “I guess I could look into it” or “That’s not how rain works”, so the dialogue itself isn’t as careful as the typography presenting it, but in terms of getting you from A to B to C, you can feel the experience and craftsmanship.

It’s hard to imagine this game conveying such authority in its historical detail if it came from another developer, either. I don’t know the first thing about 16th century Europe, but I believe what Obsidian’s telling me about it.

Don’t for a second expect it to zip along like The Outer Worlds or The Stick of Truth. Or even Pillars of Eternity. But if you’re in no particular hurry, there’s a characterful period piece here that reveals life in the 16th century, hour by hour, meal by meal, and also somehow crams in a giant timeline of player consequences. And did Mike Leigh ever manage that?