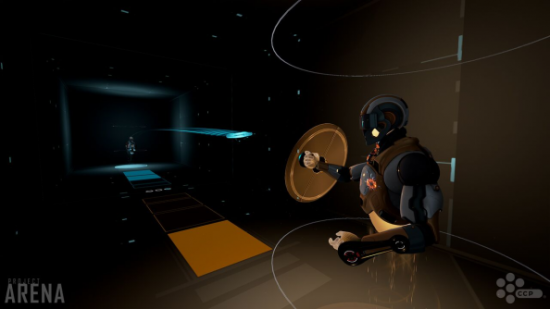

Your opponent isn’t really there. Strapped into a VR headset, standing in another room, living perhaps on another continent, they can’t possibly be. But in the Arena, ‘really’ begins to feel like a pedantic distinction. Rigged up to Oculus Touch controllers and Kinect-style body-tracking, your rival is physically present in most ways your brain cares about. They’re visibly shifting their weight from one foot to the other, examining the orange energy shield attached to their forearm, slowly raising the middle finger of one hand and gesturing in your direction.

It’s early days, but these are the best VR games on PC as it stands.

Formalities out of the way, the missiles start flying. First you learn to block with your shield – and then to hurl it. It’s Tron rules: with a swing of your arm, the disc is sent spinning down the long corridor to your enemy, ricocheting off the back wall before returning to your wrist.

The problem is that when your shield is whizzing through the air, you’re defenceless. So you learn to dodge, sidestepping your opponent’s plate as it zips by. And then a strange phenomenon occurs.

“You start to posture,” says CCP’s architect programmer, Adam Kraver. “You start to pose.”

Once you’ve uprooted yourself, you begin to play with body language – throwing out off-putting feints and that-all-you-got shrugs. Competing in Project Arena becomes a performance.

The VR Labs team behind Arena are what remains of CCP Atlanta – the studio that once hoped to follow up Eve Online with World of Darkness. When the vampiric MMO was cancelled, a small crew stayed on to experiment with full-body VR. Project Arena is the result.

First demoed in nascent form at Eve Fanfest 2015, the game always had Kinect tracking (it was later removed from the set-up) – but players originally threw their discs along prescribed paths.

“The body representation was absolutely fantastic and seeing the people around you was amazing,” recalls Kraver. “But the Kinect wasn’t as good at tracking a precise throw.”

The appearance of Oculus’ new Touch controllers, which look silly but feel natural enough in the hand, allows Project Arena a more granular, physics-based throwing system. There’s a bit of gentle homing involved – enough that “years of practice” aren’t necessary to hit your opponent – but accuracy is key, and Arena now feels as much like a traditional sport as it does a videogame.

Any good performance deserves an audience, and with that in mind CCP have been working on a spectator mode. Players begin the Project Arena demo looking down on the action, as if the court were situated in the centre of a stadium.

“We want to be able to have multiple people in this courtside space watching a live game take place,” explains Kraver. “The spectating aspect is really important to us, because we want it to be a sport.”

Spectator sport, as CCP see it, is a form of emergent drama. It’s made up of moments – a player deflecting a disc and sending their own chasing after it, for instance, leaving their opponent desperately reaching for the incoming shield. What’s more, it encourages the insulting body language we were so taken by – or “expressiveness”, as Kraver calls it.

“It turns out when you put somebody in a costume and put them on stage, they act out,” he laughs. “Everybody hams it up, and you want that. You want that thing where it’s like, ‘That is a real person.’”

That palpable, human connection is a powerful thing. Project Arena players at this year’s Fanfest stood opposite each other – but the game could just as easily bring players who are countries apart physically together, reuniting distant friends for sci-fi sport sessions.

“The thought of being able to do that over long distances is incredibly compelling,” agrees Kraver. “I think part of the reason we haven’t seen a lot of this stuff yet is that it’s not an easy task. It requires a tremendous amount of equipment and the right kind of people.”

About that: though the game is undoubtedly better off for its tech upgrade, it currently requires three bits of expensive kit to run. Is Project Arena a real commercial prospect?

“CCP firmly believes in the future of VR,” says Kraver. “We know it’s going to go so far beyond [the currently available hardware] – this is only the beginning dribs and drabs. We’re a very small team, we don’t have a ridiculous budget, [but] we’re able to iterate very fast, get stuff out and show the potential of it.”

Kraver draws a parallel between Project Arena and Eve VR – the prospective space dogfighter unveiled one Fanfest that went on to become Valkyrie, proud Oculus Rift launch title.

“They called the people of Fanfest the midwives of Valkyrie, and that’s part of the reason we’re here,” he explains. “This is an opportunity to validate the idea and that we’re on the right path. That will help inform whether this is an investment worth making. Personally I think it’s a no-brainer, [but] there are smarter people than me making those decisions.”