“I’m sorry,” Viktor Antonov tells me. He’s apologising for speaking over one of my questions – he knows it’s impolite, but there’s an important point he wants to get across. It’s a manner befitting a rare artist who has managed to sell their individual character across a series of triple-A productions – a scale that more often tends to dilute personality and erase authorial flourishes.

The point the acclaimed art director is making is this: he’s trying to get back to the situation that produced the worlds of Half-Life 2 and Dishonored.

When Viktor Antonov designed City 17, clamping the totalitarian vice of the Combine quite literally around the austere, beige buildings of an Eastern European metropolis and giving them a squeeze, it was as part of a team of no more than 30 at Valve.

The situation was much the same at Arkane, where he first adapted the tall chimney stacks and wide walls of old Edinburgh for Dunwall. Pre-production ran for an unheard-of three years before the studio swelled to the orchestral size of contemporary triple-A.

Now, at Parisian studio Darewise, he’s back in that same sweet spot – working with 20-odd others to invent a whole sci-fi planet, drawing the ground plans that a far larger team will help realise. Right now, he’s enjoying the conceptual phase that is his element.

“I’m trying to recreate this experience of building something that’s unique and handcrafted,” he says. “I compare game development often to putting a jazz band together. It’s about jamming. Without bigger responsibilities to face you can really bounce off ideas in a very dynamic way and get an energy going.”

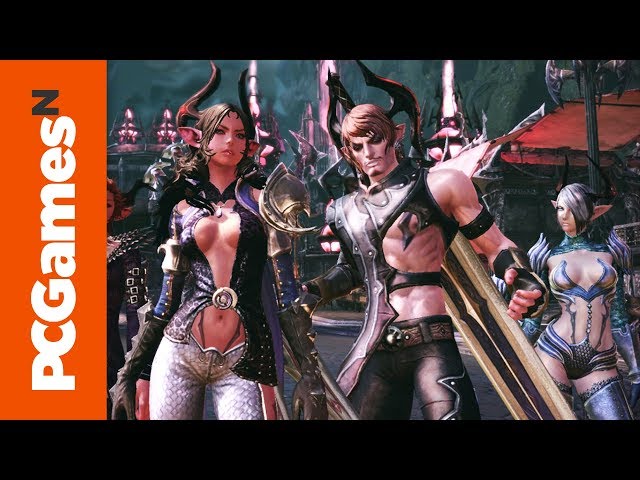

Not long ago, Antonov held the title of visual design director at Zenimax, a position that saw him straddling many of Bethesda’s internal studios. For a time, it seemed as if he retained his voice even in that far-reaching role. BattleCry, an alternate history fighting game developed by the studio of the same name, bore all the hallmarks of the art director’s style – hard lines, uncomplicated textures, and architecture that layered 20th century history and political change, one on top of the other.

This was a Europe which, tired of bloodshed, had resolved to settle its differences in skirmishes rather than wars. Its maps were characterised by the signs of rapid and recent industrialisation – the railways that mobilised nations for cross-continental bloodshed.

Then BattleCry was cancelled. It’s worth noting that Darewise is a venture capital-backed independent, set up by a former monetisation director for Assassin’s Creed named Benjamin Charbit. Triple-A without publisher strings might just leave them in a safer position.

The arrival of steel and suffering to once sleepy locales is a perennial theme in Antonov’s work, so it’s fitting that Darewise’s Project C concerns the colonisation of an unmapped planet. He’s working at far greater scale than before, filling the enormous MMO spaces cloud servers from Improbable are beginning to enable.

These are tracts of land far too large to be designed entirely by hand, so Darewise is turning to procedural generation to populate the planet.

“On the surface, using procedural technology may seem like a contradiction to handcrafted,” Antonov says, “But it’s not. An example is the way architects work today. They’re leaning more and more towards procedural tools like Grasshopper. It means you have to create a really strong logic to your world, for your rivers, for your forests, and then turn this logic into an algorithm so it can be reproduced. This is what I love doing – very consistent worlds.”

Some of this logic might seem self-evident – a tree cannot grow on stone, nor a forest in a river. But in time it builds into the kind of strict design laws Antonov established on previous projects – clear parameters for his team to follow in creating their world.

A common theme of Antonov’s work is the life behind the facade. It’s a curious philosophy to bring to the MMO genre, so often concerned with the exterior grandeur of cities like Stormwind in World of Warcraft or Divinity’s Reach in Guild Wars 2.

Related: Whatever happened to Half-Life 3?

“If I took a traditional town, I would definitely go on the rooftops and explore the cellars, the courtyards, everything that’s hidden from the tourist’s eye,” Antonov says. “Just to show the nature of the beast. When you approach a mountain or a forest in Project C, it’ll have surprises layered behind and within it. I’m very interested in the story that is not a linear plot where you have a superficial conflict, but the real story that is the world and the context.”

In fact, Darewise consider the planet Project C’s central character. The world is the subject of a gold rush after the discovery of a valuable resource, but it’s by no means a passive victim to be plundered.

“It’s a protagonist and antagonist at the same time that reacts to your actions,” Antonov says. “The world is a living character, more living than a character in a linear shooter. After so much Google Earthing and so much knowledge about everything, this place is a savage, unexplored land, comparable to Alaska at the beginning of the 20th century. You’re there to master it.”

Darewise won’t be drawn into details about the mechanics used to explore and conquer the planet, other than to say that they won’t resemble the traditional MMO paradigm of collecting and destroying. Rather, we’ll be building, farming, and finding a way to live with the other entities in the planet’s deep ecosystem.

“If World of Warcraft is the gaming version of Disneyland, what we’re trying to do here is Westworld,” Charbit says. “A world that is really alive and that player’s actions can impact.”

It’s a vague but exciting concept, made impossible to ignore by the presence of Antonov. Colonists in Project C will soon discover that the entire planet has been biologically engineered by a prior inhabitant – and it’s hard not to imagine that this absent sculptor is Antonov himself.

“I often compare boulevards to rivers, and skyscrapers to the mountains, because they have their own growth,” he says. “For me, a city is a creature. So now I’m applying the same rules that are used in urbanism to bigger scale ecosystems. It’s the last wilderness in the galaxy.”

Darewise is planning to invite a small number of players into a closed alpha in April.