With the release of Black Mesa Source [Black Mesa Source Download links are here], we thought we’d republish this piece by Richard Cobbett, on what the original Half-Life is like to play today.

The problem with Half-Life is that while you can reinstall it and replay it, you can never hope to relive it. You had to be there to appreciate just how many rules it broke – how many of its seemingly obvious ideas had simply never been done before. Never removing control for instance, with its equivalent of cut-scenes letting you take part in big events instead of simply watching them. A sprawling, continuous world that flowed (almost) seamlessly from sneaking through underground labs to having epic firefights on the surface. AI that worked well enough that you’d only kill your sidekicks for amusement, never out of frustration. For 1998, this was the equivalent of inventing the lightbulb, television, and Mars Planets in one go. Oh. And it was a great FPS as well.

Half-Life’s impact is all the more impressive in context. As badly as many shooters of the 90s have aged, this was a time of staggering innovation for the genre – and for most of Half-Life’s development period, it wasn’t even a major contender. Sure, it got positive previews, and even a couple of Best of E3 awards, but it remained a plucky underdog during most of its development. John Carmack openly admits that it was the Quake license he had the least interest in, early trailersand screenshots were rubbish, and most importantly of all, even Valve had such little confidence in it that it ended up scrapping and rebuilding the whole game a year before release. Not out of the perfectionist belief that it wasn’t good enough, you understand. It simply wasn’t working at all. Hard to imagine, isn’t it?

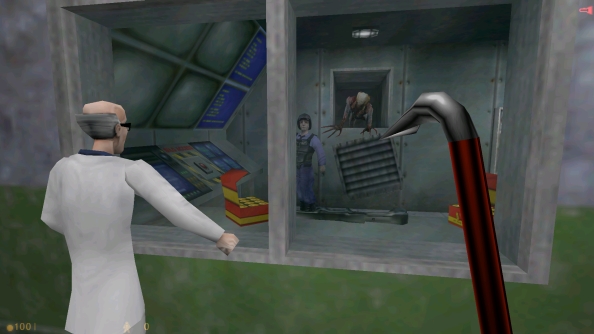

But enough history. Playing Half-Life now, sadly many of its charms have long since faded. The once majestic Black Mesa compound – a research facility which apparently splits its time 50/50 between inter-dimensional experiments and cloning its own staff – is now a series of mostly grey hallways with the occasional bright green goop lake. The enemy AI which once blew us away by daring to actually be competent (a massive deal in 1998!) is probably best, if politely, described as ‘functional’. Xen is even worse than you remember; a poxy platform planet where the last third of the game deflates with a dull farty noise.

One achievement remains though, and arguably the most impressive – just how much it keeps you off-balance through both storytelling and basic mechanics. Early levels in particular are full of beautiful stuff. The calm before the storm as you take the monorail into work, suit up and descend into the bowels of Black Mesa establishes so much about the universe without tiresome infodumping – not least showing you almost all the areas you’ll eventually be exploring, and demonstraing just how how freaking huge the world actually is. A single line from the guard who becomes Barney in Half-Life 2 establishes that main character and professional Hugh Laurie impersonator Gordon Freeman actually has a life and friends… even if his security clearance is so low that he can’t get into the janitor’s closet. It’s also notable, on a subtle, sinister level that only pays off at the very end of the game, that the quick description you get of him at the start of the game begins with the word “Subject”. It’s never too early to start foreshadowing, after all…

When things go wrong though, everything really kicks into high gear. You face headcrabs before you have so much as a crowbar to defend yourself, and there’s a massive contrast between the sleek, efficient lab you walk into and the collapsing chaos through which you have to retrace your steps after accidentally blowing everything up in the name of science. There’s something deeply visceral about having to smash the glass of a door that previously slid open for you, not to mention the sheer panic on the faces… in the voices anyway… of the scientists who were previously so happy to poke the universe for fun and profit.

Half-Life’s genius is that every time you get comfortable, the rules change in some way, while always feeling part of a coherent whole. Early levels are survival horror, with zombies pawing at corpses and headcrabs leaping out of the darkness. When you’re done going “Aaah!”, puzzles start appearing – like getting across a flooded room without being electrocuted by an inconvenient live wire. Shortly afterwards, right as you get used to fighting the brainless animals who make up most of the alien troops, proper soldiers are added who fight with actual tactics and advanced weapons like grenades.

It continues. Epic battles on the surface then give way to quieter platforming moments down below, where a sudden headcrab attack can feel novel again, and facing off against puzzle bosses like the Gargantua – a boss you have to take out by reconnecting the power and shocking into submission. Chapter after chapter, you never have any idea what’s coming next – but very rarely does it disappoint. Except Xen, obviously. Xen sucks like a vacuum cleaner in a quantum singularity. What the hell were they thinking?

Easily the best individual section is the Blast Silo section, where you have to sneak past three blind tentacles that hunt by sound. Half-Life has many great moments, but this is one that was not only incredible at the time but has never really been replicated. It’s not simply that you have to get past them by crouching down and moving slowly, always waiting for detection and death. It’s that they’re aware of your presence and playing the world’s biggest game of Blind Man’s Bluff – their claws constantly clanging around you as you slowly descend – and ringing in your ears even when you’re out of the room.

Even in a modern shooter, this would be a great moment. Now bear in mind that the original Thief – the first major game to experiment with stealthiness via sound as well as hiding in the dark – only came out in the same month as Half-Life. As tense as crawling around this section to active the rocket that fries the tentacles is now, in 1998 it was like staring into the face of God and realising he looked like Gabe Newell.

Looking back on Half-Life some fifteen years later – give or take – its importance can’t be overstated. As an shooter, that goes without saying. It single-handedly jumped the genre forward several years with both amazing acts of design, and technical innovations like using skeletal animation so that enemies could actually respond to your actions on the fly, instead of working purely at the whim of their canned animations.

If Half-Life’s success has any real downside, it’s that it overwhelming popularity put the last nails in the coffin for many other approaches to single-player FPS design. Its 1998 rival SiN for instance offered much more exploration in its real-world environments, heavy interactivity, and even had events on one map physically affect others in various ways. By comparison, Half-Life was a corridor. Nobody really remembers the alternative though, partly because of SiN’s buggy release, partly because of its pathetic obsession with its its leading lady’s lady parts, but mostly because Half-Life’s sheer quality completely obliterated its rival to the point that it may as well not have happened at all.

(Adding insult to injury, the same thing happened again when the much, much less interesting SiN: Episodes was stomped into the ground by Half-Life 2: Episode 1)

For Valve specifically though, the making of Half-Life set a pattern that continues to benefit us all. Unlike most start-ups, they had the luxury of enough money to simply start over and get it right the second time, but the success of the result meant that they could continue to do so with future games. Half-Life 2 for instance began development in 1999, and didn’t come out until 2004 – an insane amount of time for any shooter back then that didn’t have the words “Duke”, “Nukem” or “Forever” in its name. Team Fortress 2 took even longer to turn from a realistic shooter into the living cartoon we know and love today. Without Half-Life repaying the gamble of waiting “until it’s done”, what are the odds Valve would ever have risked something so dangerous again?

For nostalgia purposes though, it’s a real shame that few games have aged as poorly as late-90s 3D games. Retro titles still have a certain class with their pixels, and more recent 3D still has a rough charm even after the initial shine has worn off, but these early 3D corridors, characters modelled by smacking a Crash Test Dummy with the business end of a shovel, the lack of things like ragdolls, and the very simple interaction density of these early worlds all take a massive toll on the fun no matter how good the core game.

Half-Life stands up better than most… but everything’s relative. If you missed it first time round, you’ve probably left it too late now. If not, you’re probably best off waiting for Black Mesa Source (currently set for release sometime around the heat death of the universe) to softly caress your nostalgia glands instead of risking a good pair of rose tinted glasses. Half-Life 2 holds up a lot better if you’re in the mood to revisit Gordon these days, especially with its Episodes. Don’t however expect the long-awaited next chapter Half Life 2: Episode 3 any time soon. At the very least, Valve has warned not to expect any new announcements at this year’s E3, and it’s been literally years since it gave any sign of still being interested in actually finishing the story.