The stroke of midnight on Christmas Eve, 1999, found me huddled in the freezing-cold office of my family’s drafty old home in Northwest Indiana. There was plastic sheeting over a poorly sealed, jammed-shut patio door, in a vague gesture at insulation. When I first entered the room, I could see my breath in the air, like I was in some kind of suburban Dr. Zhivago.

But I didn’t care how bitter the cold was. I couldn’t sleep and I needed something to take my mind off of… everything. So I spent Christmas Eve shivering in my pajamas playing Novalogic’s Delta Force, my feet slowly going numb and my hands starting to ache from the cold. I barely noticed. I was the Roland the Thompson Gunner of the unending war on the US EAST TEAM KOTH OFFICIAL SERVER. It was a place where I was good, and talented, and at peace.

As this comes from a former fanboy, take this with a grain of salt. But I still say Delta Force was ahead of its time, a precursor to the modern military shooter. It wasn’t as tactical or demanding as a game like Rainbow Six, but it offered something that nobody else did: huge battlefields that at least suggested the scope of modern warfare.

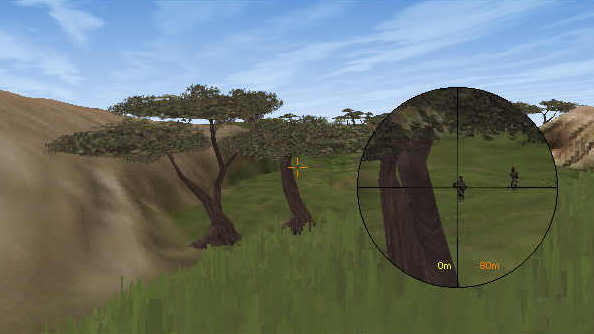

It was able to do this because of NovaLogic’s singular love of the voxel at a time when everyone else was trying to adapt polygons to more natural settings, with mixed results. Spec Ops: Rangers Lead the Way, a contemporary game that would ultimately lead to a more successful series, never managed the trick. Its portrayal of the ex-Soviet countryside was as a flat table dotted with telephone-pole like trees and pyramidal hills. Delta Force, however, managed an incredibly detailed and nuanced treatment of terrain that games really only started matching in the last five or six years.

The trade-off for all these convincing gulches, glens, and hillocks was the voxel’s signature blurriness. Delta Force had some of the most astonishing vistas PC gaming, but things that looked tremendous at 250 m looked like mud photographed through a greasy lens when you got close. But that’s actually what made Delta Force so different, and why it became the first multiplayer game I became well and truly obsessed with.

By the end of the 1990s, PC gaming was really split between the broadband haves and have-nots. Tell me how you felt about Quake 3 and I’ll tell you what your connection speed was, or how far you were from a LAN center. Shooters seemed to be designed for a twitchy, fast-paced world where sixteen people were playing together and getting rocketed to death the instant they were spotted. They played at a level where milliseconds mattered and, more importantly, so did a stable and reliable connection to the internet. My shaky 14.4 kbps connection didn’t belong in that world, and neither did my more deliberative style of play.

Delta Force felt tailor-made for me. With engagement ranges of half a kilometer across sprawling open battlefields, combat and movement were measured in minutes rather than fractions of seconds. Furthermore, while the voxel landscape looked tremendous in some ways, it had some …oddities. It seemed to shift around you as you moved, almost shimmering. This meant that players’ character models blended into the environment and sometimes were almost swallowed by it. Was that distant cluster of pixels an odd bit of the landscape juddering about as you moved, or was it a sniper drawing a bead on you with a .50 caliber Barrett rifle? The magic of voxels was that you had no idea.

Delta Force came out in 1998 and I got into it a few months later. But by the winter of 1999, the servers were shutting down and the community was starting to dry up as people moved onto Delta Force 2 or other games. Those of us who remained, however, were very, very good.

The hold-outs

In our dwindling numbers, we stopped being strangers on the Internet. We were like an armed forum, a community that sprang into being to fight over a magic circle drawn on a map, night after night. You’d see the same twenty of thirty handles come in and out of the server every night. USMC_0223, WHITE KNIGHT, Zapata, SAWMaster… sometimes we were on the same team and sometimes we weren’t. We feuded, we banded to together to deal with the hackers who sometimes overran the servers, and above all we played some of the best Team King of the Hill matches I’ve ever seen in any game.

With hundreds of hours under our belts, we were ridiculously good at the game. Team King of the Hill was where the best players congregated because it actually made all the weapon loadouts useful, and it organized the battle in such a way to minimize the role of blind chance. I remember once a few Deathmatch and Team Deathmatch die-hards showed up to trash-talk us. A couple of us decided to head over into their servers and, for the rest of the night, we basically shut down the deathmatch communities, even without knowing the maps. It was like setting the Predator loose on a Boy Scout troop.

I saw things in Delta Force I just didn’t encounter elsewhere. Spotter / sniper teams calling out enemy movements via team chat. Support gunners using their SAWs to hose down hillsides and villages while assault troops stormed forward. Entire battles taking place away from the main objective over terrain features that both teams had learned, through months of experience, were vital to controlling the Zone.

I had a sense for the game other players didn’t. I knew where snipers would be almost before they did, and knew just how to approach across a kilometer of seemingly open ground without ever being seen. I learned the best concealed positions were the ones nobody knew to look for. High ground was a death-trap, and amateur’s idea of where a sniper would nest. The most effective sniper isn’t as far away as you think, and he’s got a narrow field of fire into which targets are inevitably funneled.

For all that I understood the craft, I hated being a sniper. It bored me, and it was ineffective in most players’ hands. If your team went overboard on snipers, you were doomed.

My own style was different. The most effective way to be a killer wasn’t to be a mile away with a high-powered rifle and scope. It was to be a hundred yards away with an assault rifle, rotating between several different known positions. Engage, kill, check your flanks, reposition, repeat. No matter how good a run you were having, you were pressing your luck if you stayed in one place for more than a few seconds. As soon as my first victims started to respawn, it was time to go.

But of course, all my great gaming love affairs are connected to a time and place in my life. Medieval Total War was my first year at college and away from home and friends. World of Warcraft was the breakup and the ensuing crackup. Delta Force was teenage awkwardness.

I hate trivializing phrases like that, though. It makes it sound like I was going through a growth spurt and having trouble fitting into clothes, or playing sports. The truth is that suddenly I didn’t seem to fit into my own life at all. I wasn’t fitting into any of my social groups, my relationships were fraying with friends and family, and I was turning into a complete failure at school. I got through it as most of us do. And it was easy compared to what a lot of other people deal with in their teens.

Anywhere but here

But the fact remains that my “awkward phase” was really about feeling like —, and being repeatedly told that I was — a worthless failure. My awkward teenage years didn’t end because I grew out of them. They ended because I left, and went to places and did things that let me be myself, and rewarded me for it.

But I didn’t see the ending at the time. I just knew the shit was really hitting the fan that winter. My grades were in free-fall, and I was so far behind in my classes I no longer had any idea what the hell half of my teachers were actually saying. Now everything was snowballing. I cared passionately about the things I cared about at all, and everything else I tried to avoid. It was starting to hurt too much. It seemed like I didn’t know how to be good at things anymore, so it was easier to make a show of not trying.

But I was good at Delta Force, which is probably why I was playing late at night on Christmas Eve. I couldn’t sleep and I was dreading Christmas morning, and having to pretend to my parents that things were fine with me, or between us. That we weren’t just making-believe that I was a good kid who deserved anything at all, and that we wouldn’t be back to arguing before the end of Boxing Day. In less than two weeks I’d be back at school and back to being gently scolded about “living up to my potential” by guidance counselors who would then cluck their tongues and tell me that I didn’t meet the standards to be in the advanced writing course next semester.

The servers were quiet that night. It was only a few of us playing on maps meant for 32 players. On a typical night, Delta Force King of the Hill was an ear-splitting cacophony of automatic weapons fire, with a corresponding display of tracer fire overhead (the official servers had some very ill-considered defaults enabled, one of which was constant tracer fire that made concealment very hard and made it look like we were fighting battles with laser-guided Silly String). On Christmas Eve, the fighting was sporadic. A burst of rifle fire here, followed by silence, and then a mournful “thunk” as someone launched a grenade into the distance.

There wasn’t a ton of action and, ironically, people were getting more dispersed as they struck out in different directions hoping to find a fight. Far from the welcome distraction I’d hope for, it was almost depressing. I was a soldier without a war. Yet nobody would leave, and we kept determinedly waging our pissant battle.

During a long lull on the box-canyon map, someone from east coast remarked, “Hey, it’s Christmas here.”

And like that, we all started chiming in our season’s greetings, and talking about what was going on. “This kinda sucks, doesn’t it?”

“Yeah. It’s not great. Not enough people.”

“Should we just call it, guys? I mean, it’s Christmas.”

Nobody wanted to call it. As we tried to work out how to salvage a lousy night of gaming, we started chatting for the first time ever about something personal. We started asking one another how we were doing. The rest of the year our communications was pretty terse, “Get inside the zone now!” or “Could someone help me at B6?” That night, we started to actually engage as with each other as people.

There were guys who were away from their families because they couldn’t afford travel home. One of our number was just a little down because there was a sickness in his family and this might be the last Christmas with that person. Everyone said they understood, and that they’d been there, too. A few people weren’t close with their families and didn’t really like this time of year.

We kept the game going and started setting new rules. You could still be a sniper, but the outer two rows and columns of the map around the control point were off-limits to everyone. Everyone needed to stick close to the center and actually fight over the objective. As new players logged into the server, we’d break down the rules really quickly in chat. Most everyone played along, and the tempo of the battle steadily increased as each time zone crossed into Christmas Day, and we once again passed around well-wishes. At some point we apologized to the Jewish player for missing Hanukkah.

It was far from the best night I ever had in Delta Force. At its most heated, our Christmas Eve battle never ranked as more than a big skirmish compared to some of the full games we managed to put together on other nights. But it’s also one of the only nights I clearly remember out of all the hundreds I spent with Delta Force. It was important, on some level, to be with people who weren’t enjoying the holiday either, who weren’t sleeping easy and who weren’t looking forward to the next morning or the morning after that. Everywhere I went in those days seemed to make me feel lonelier and, ironically, it took a midnight gaming session with a bunch of strangers to remind me that I wasn’t alone. That we were all in this together, even if we’d never be anything more than callsigns trading shots from across open fields of voxels.