When I admit my love for Frogwares’ Sherlock Holmes adventure games, I make it sound like I’m confessing a secret vice. It’s a little silly. Yes, they’re a bit stiff, often obtuse, and occasionally quite odd, but they offer refreshing traditional consulting detective adventures in the face of the character’s constant reinvention.

There’s Sherlock reimagined as, well, Robert Downey Jr., as a recovering heroin addict in modern New York, and as a tall man-child, but I’ll take Jeremy Brett’s portrayal over those any day of the week, and that’s what the adventure games are like. But occasionally there’s Elder God cults and Jack the Ripper.

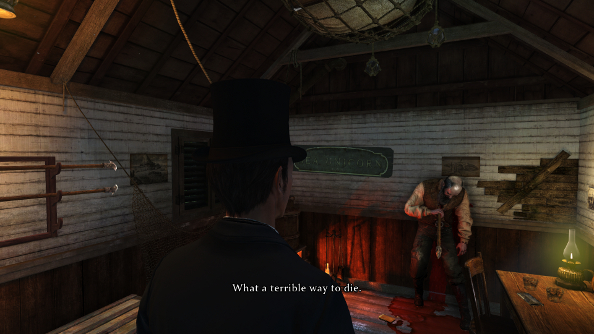

Holmes’ latest escapade, Crimes and Punishments, is probably the best of the lost. It’s trite marketing, but when Frogwares said that it would let you become Sherlock Holmes, it was a statement of intent that the developer has really tried to follow through on. And I blooming love it.

One of my first adventure game obsessions was Police Quest. It probably skewed my idea of what adventure games can be, because it was so much more than puzzles and witty dialogue. It was a simulation of what it was like to be a police officer, created by, at least in part, by a police officer. This was an adventure game where firearm maintenance was important, just as adhering to regulations was.

I was a cop; I was Sonny Bonds.

This is how Crimes and Punishments has made me feel. It is not quite as obsessed with minutiae, and Holmes isn’t one for regulations, but it captures the essence of Baker Street’s most famous resident.

It’s an anthology, six separate cases for Holmes and Watson to investigate, and this format allows it to cover a lot of ground and draw inspiration from the rich library of the detective’s investigative romps.

So the first case is a classic “whodunnit,” a murder and a growing list of suspects that manages to tell multiple stories, from ill-advised affairs to crimes at sea. It’s set in London, with Holmes visiting Lestrade at the police station, the docks, Baker Street, and other spots in the city. All classicly Holmes.

But with that case closed, we’re off to the country to visit a bee keeper. That’s not important, but what happens afterwards is. Watson and Holmes and waiting for their train when, just as it gets near to the station, it vanishes, seemingly into thin air. Time for a new case, Sherlock Holmes versus The Ghost Train (is what it should have been called. Appropriately, Holmes is exceptionally excited about this.

In previous games, Holmes has been more like an agent and a handy tool, or an archetype that’s too iconic to seem properly human. This time around, he’s been replaced with a version who has a life, and we get to step into that life, even guiding it.

Being Sherlock Holmes comes with responsibility. When it comes to solving the case, all power rests with the player. It’s not a simple matter of gathering all of the evidence and knowing exactly who the culprit is, because there are multiple suspects, all with potentially good reasons to commit the crime. The rest is up to deduction.

When the case is ready to be solved, we delve into Holmes’ brain, connecting nodes in his noggin together to create a narrative. Often these nodes will offer to different takes on the evidence, though. Accepting different versions of the story gives life to different conclusions. And mistakes can be made, and then have to be lived with.

The accused is always considered guilty, because it’s Sherlock Bloody Holmes, and who’s going to argue? But there is only one right answer, no matter how possible the other ones seem. Thus, there’s a lot of weight to each investigation, a life on the line. The game offers many opportunities to change the decision, like Chris Tarrant constantly demanding “are you sure” on Who Wants to Be a Millionaire. It’s Holmes wondering it himself, a moment’s hesitation that nobody else sees.

He’s got more power over the suspects that just the ability to accuse them, though. He’s able to show mercy, too. Again, this is all about deduction, rather than just playing Holmes as a nice, sympathetic fellow versus a law-abiding rulebook-lover. He’s certainly not the latter, and he’s not really the former, either. He’s more concerned with the challenge of solving a case, which explains his sometimes uneven relationship with Scotland Yard.

But he does have his own moral compass, which he often uses in the books to break the law in an attempt to assist clients. And in Crimes and Punishments, it’s this that allows him to let criminals go free or suggest a more lenient punishment. When choosing either option, a logical reason is given, an interpretation of the facts.

By giving us, the players, the ability to make these judgements, Frogwares makes us Sherlock Holmes. We must make the important decisions, instead of following an unbreakable, linear script. With the evidence gathered, the conclusions are, mostly, our own.

With all that pressure bearing down on me, I’m that kid in the early ‘90s again, playing cop, trying to solve crimes and definitely being out of his depth.