Since its big break in 2015 with PS4 exclusive Until Dawn, developer Supermassive has dabbled in nigh-on every horror subgenre, from slashers to the supernatural. Its games draw on recognisable horror characters and settings but are able to effectively re-examine – and reinvigorate – established tropes through their branching narratives, technical prowess, and clear affection for the genre.

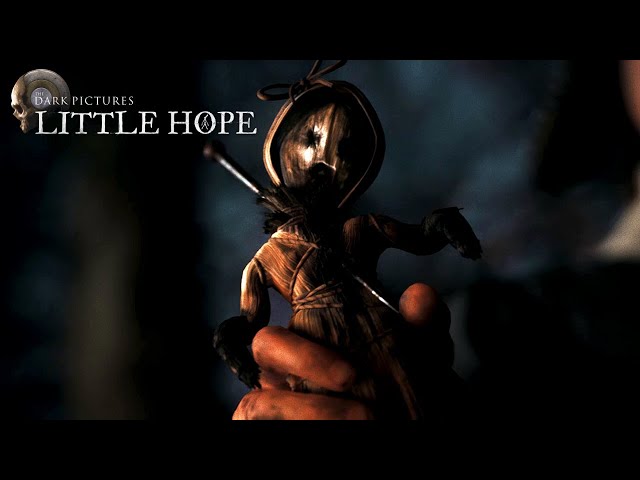

The team’s next release is The Dark Pictures: Little Hope, the second entry in a planned anthology of horror games. Each instalment is intended to be a standalone title with its own setting and cast of characters, though they’re unified in a way by their shared interest in the darkest parts of human history. With Little Hope, Supermassive has returned to the well of America’s past to tell a most horrifying tale.

From Silent Hill to Stephen King’s The Mist, a small town shrouded in mysterious fog has become one of the horror genre’s recurring nightmares. Dan McDonald, series producer on The Dark Pictures Anthology, explains that Little Hope uses its familiar setting to tell a story that is anything but. You see, the eponymous town’s history is inspired by that of Andover and Salem. And what do they both have in common? Witch trials.

After you find yourself trapped in Little Hope, its dreadful past returns to meet you head-on. You’re soon dragged back to the 17th century to witness accusations, trials, and executions. “Oh, and there are demons in the present day trying to drag you to hell,” McDonald adds.

The witch trials weren’t always Little Hope’s intended subject matter. McDonald recalls that an earlier idea revolved around a group of people being hunted by a supernatural force through an abandoned town, bringing to mind Resident Evil’s Mr X or the body-hopping monster from It Follows. This no doubt would have made Little Hope a radical departure from both its direct predecessor, Man of Medan, and Supermassive’s highly directed style at large. That said, the team found other ways to innovate.

Where Man of Medan largely took place on a cramped, claustrophobic ghost ship, Little Hope’s empty streets and abandoned buildings make for a decidedly more open setting. Naturally, this demanded a number of alterations to the established formula, including the addition of a flexible camera.

If you’ve played the earlier Silent Hill or Resident Evil games, you’ll know how effective a fixed camera can be in creating a sense of unease. There’s something about the lack of control that just works for horror – you can’t simply look away. This in turn allows a developer like Supermassive to pull cruel tricks aplenty.

Little Hope switches between a fixed and free camera to allow for both exploration and directed moments of terror. The nasty realisation that your control of the camera has been sneakily pulled away should be enough to set your pulse racing.

It’s witchcraft: We paid a witch to make us better at Apex Legends

Immersive sound design is another key element of Supermassive’s approach to horror. For Man of Medan, the team recorded the clanging and groans of an old military ship, and even headed out to sea to capture the crashing of waves. “When you add that all together with the cameras and the lighting and a storm raging outside, you really do get a sense of dread and foreboding. We wanted people to feel uncomfortable,” McDonald says.

In this respect, Little Hope is no different. Its grisly tale plays out in the dead of night, and its atmosphere is very much rooted in its small-town setting. We’re talking blinking streetlights, deserted buildings, dark wooded paths, and troubling animal noises.

Creating a memorable setting is one thing, but Supermassive then has to fill it with characters – and, in this case, monsters – that can sell the intensity of the script. The Dark Pictures employ complex body and facial capture techniques (not to mention Hollywood talent) to achieve these results. The games are generally about human emotions under unimaginable stress and terror, McDonald explains. “You can only really convey those emotions within the game through a motion capture performance. It brings a heightened sense of realism to the games.”

That said, simply recreating existing cinematic experiences within a videogame has its limits. You don’t just want to regurgitate the same tropes and tricks present in mainstream horror cinema without playing to the strengths of the interactive medium.

“Horror films do have a certain set of rules that you often see in the movies, and we do apply a lot of these into our games. However, we like to subvert the horror genres,” McDonald says. With Man of Medan, the team played with elements of the home invasion thriller, the supernatural, and the ghost ship story, while Little Hope features witchcraft, demons, and hell. “You don’t often get that mix with traditional horror films, but we can easily do this in games because our stories have multiple paths, with complex storylines told over several hours.”

But therein lies one of the team’s biggest technical challenges: “there are huge complexities around having multiple branches of the story with multiple endings,” McDonald says. “From a design perspective, you have to make sure everything ties up and makes sense regardless of the choices the player makes. I would liken it to one of the telephone exchange boxes you see people working on – lots of different threads that all weave within each other but ultimately all make sense within the realms of the story.”

This proposition gets even more complicated when you add multiplayer to the mix. With Man of Medan, and now Little Hope, the team incorporated two distinct multiplayer modes: Shared Story and Movie Night. The former allows you to play online with a pal and make decisions that will affect you both, while the latter is a couch co-op experience for up to five players.

For the online mode, the team had to be sure that the narrative would sync coherently for both players while also factoring in that one player might progress faster than the other, leading to immersion-breaking wait times. It’s a “pretty extreme use case” for Supermassive’s chosen engine, Unreal 4 – despite the engine’s ubiquity across the industry, there’s not a lot of precedent for linking branching narratives in a multiplayer context.

Fortunately, the engine’s flexibility has enabled Supermassive to devise a solution. “We have the benefit of being able to write custom tools and runtime systems that seamlessly blend with the rest of the engine.” McDonald ultimately believes that the team achieved efficient results due to the nature of the engine architecture and some of Unreal’s helpful tools, such as the customisable sequencer editor.

Supermassive’s adoption of Unreal Engine 4 for The Dark Pictures Anthology made sense for a number of other reasons too, most notably the need for it to be a multiplatform series, McDonald explains. “Right from the outset we had always set out to make The Dark Pictures Anthology multiplatform, so we obviously needed to use an engine that catered for that. Unreal has a fantastic set of tools and allows us an incredible amount of flexibility as we have full source code access, which in turn enables us to make the engine version we use very much bespoke to us.”

Read more: Check out the best horror games on PC

Thanks to its technical wizardry, genre expertise, and ambitious approach to storytelling, Supermassive looks set to make old tropes sing once again with The Darkest Pictures: Little Hope. It launched at the end of last week, just in time for Halloween – here’s a link to the Steam page.

Unreal Engine 4 is now free. Unreal Engine 5 is due to release next year.

In this sponsored series, we’re looking at how game developers are taking advantage of Unreal Engine 4 to create a new generation of PC games. With thanks to Epic Games and Supermassive Games.