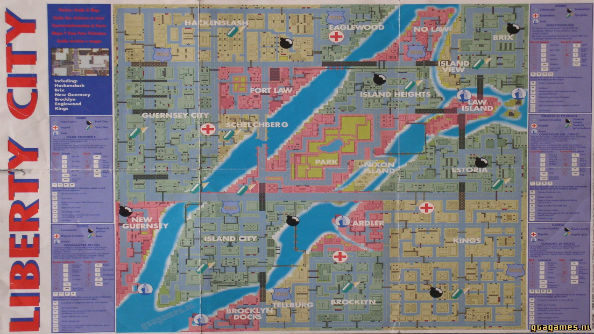

It never rains in this city. No clouds, no hail, no snow, just sun. That’s good driving weather and today you feel like exploring. You see, you’ve come to realise that the sirens and gunshots and midday traffic fanfare of Liberty City too often hems you in. But this city is huge: Hackenslash to Kings, Brix to Brocklyn. Today you’ll see it all. Today you’ve nowhere to be.

Unless…is that them? That sound. The sound of a procession. The sound of a group of revellers. Of tambourines and of drums. You accelerate round the corner. You spot them. You close in. You’ve got one shot to get this right. You line it up. Bang. Seven marchers downed. They fall like dominos. Job done.

“GOURANGA”

If you played DMA Design’s – now Rockstar North – sprawling sandbox Grand Theft Auto in 1997, you’ll undoubtedly hold this scene close to your heart. Ploughing through the seven-strong team of jubilant Hare Krishnas – having the ‘Be Happy’ axiom hang on your screen for the few seconds that followed impact – ascended comical distraction. Silencing their incomprehensible rabble as you toured around the faux-NYC cityscape was a rite of passage.

“It wasn’t really intentional,” explains the game’s writer Brian Baglow. “When we were in the middle of development, one of our programmers was looking at the pedestrian behaviour and trying to make it look as natural as it could for a top-down game. He basically made an algorithm that made several of the characters follow each other so you’d get a little line of them going down the street. Being top-down, we couldn’t do anything visually apart from change the colour of their clothes..

“What could we do with a line of people walking down the street, then? I’ve no idea who it was that suggested Hare Krishnas but they had the chanting and the tambourines. Okay, so now what do we do with them? Well, let’s run them all over. What happens when you run them all over? Well, you call it Gouranga – be happy. It was really cheap ways of getting the most bang for your buck with an engine that really wasn’t capable of any level of sophistication.”

Four years prior, Grand Theft Auto began life as a cops and robbers-type racer named Race and Chase. Mike Dailly – DMA’s first employee after the company was formed by David Jones in 1989 – had worked on breakout hit Lemmings in 1991, and its success had raised the Dundee-based outfit’s profile to global level. They began working on several titles concurrently across a number of platforms and grew considerably in numbers, bringing in several new faces who’d never worked in the videogames industry before. Baglow was one such individual when he signed up in ‘94.

The newbies would be assigned to Race and Chase, a game that the higher ups didn’t expect much from, that’d be run on a sandbox engine – an underutilised concept due to technical constraints at the time – that Dailly had been tinkering with. It became clear very early on, though, that it couldn’t work in its current state. Assuming the role of the police in this ambitious playground, it turned out, was incredibly dull and what made it fun – knocking over pedestrians, running red lights, tearing up public parks, generally breaking the law – could only be justified on the other side of the divide: that of the criminals.

“Just that mindset alone,” says Baglow, “without changing the game in any way, all of sudden made you go, ‘oh yeah, that’s quite interesting’. This was one of loads of ideas that were thrown out there at the time but this was the one that made all the crucial difference.”

This distinct change in direction would have a profound knock on effect on the game’s development process. Suddenly, the renamed Grand Theft Auto posed so much potential in its mission, size and scope as aimed to realise its potential. Baglow describes the team’s ethos at the time as one of unity and togetherness but also one which at times lacked structure.

In search of inspiration they pored over their favourite gangster movies and gritty television crime dramas and came up with ideas on how to translate these influences into the game. They mapped out their criminal overworld on A0 graph paper. If an idea sounded cool, it was thrown in with little thought or concern for how it might further complicate things down the line.

It’s fair to say this would’ve challenged even the most experienced development team, but for a group of what was in essence beginners, albeit capable ones, it led them into trouble. Deadlines were delayed, milestones were missed and communication between departments became an overly complicated process.

“The hardest thing, even more so than the non-linear aspects of the game,” tells Baglow, “was just trying to show the player why the crap you were doing all of these varied tasks.” The designers, he recalls, worked independently from the writers creating levels before passing them over to be scripted.

What this meant was that Baglow would receive a working section of the game – say, an entire mission – with the task of factoring in scrip, story and context afterwards. He might receive a segment that sees the player working through a series of tasks – “go here, jump in this car, drive it to this point, drive to a building, run out on foot, get on a motorbike, shoot a guy and so on” – and it’d be up to him to glue it all together.

Overall, this process was made all the more difficult by the fluid nature of the game’s sandbox. Missions could be undertaken in almost any order, thus ensuring the script reflected a similar level of flexibility was crucial. So as to deliver a certain sense of familiarity, Baglow decided against including throwaway characters, instead relying upon a recurring cast that the player would happen upon two or three times across each map, mostly in comedic circumstances.

One such character was the daughter of the Liberty City mayor. “This poor you girl,” he says. “If a car got blown up she was in it and was horribly injured; if there was an ambulance that you had to steal or drop at the docks, whatever, again it would be her. It didn’t really matter what order they happened in because it was simply a series of unfortunate events.

“Of course, the designers were building missions to take you from one side of the city to the other whilst giving you a nice variety of activities along the way. I had to just try and make sense of it in a narrative way.” He laughs, before adding: “There were a few wee arguments over the course.”

The haphazard approach to development, not to mention the slew of overrun targets, hadn’t went unnoticed by publishers BMG Interactive. They raised concerns via weekly conference calls from the US. On more than one occasion Grand Theft Auto was almost scrapped entirely.

“It was under constant threat of cancellation,” admits Baglow. “It was entirely new, nothing else like this had been done, but at the same time it didn’t look groundbreaking – it looked like this silly wee top-down game that was only two dimensional, despite the fact you had X, Y and Z axis. I nearly punched more than one person that said it wasn’t 3D. We were competing against things like Tomb Raider, that had come out not long before us and some of the levels in that were awesome.

“You thought: this 3D thing could be really quite big. For the longest time we were adding new things into the game, new ideas, a new graphics engine, all of these different things, and of course what it meant was that nothing was getting fixed.

“At least three quarters of the game’s development we had no idea what was going to appear at the end. In fact, I’ll go further, it was probably about six sevenths of the game’s life – it could’ve been a horrible disaster. The publishers were nervous about it and really weren’t sure if it was going to big and if they should continue to support it and if it was actually going to produce something of any value at the end.”

Needless to say, when Grand Theft Auto did eventually launch in the October of 1997, it did produce something of value – financially and conceptually. The baptism of fire, as it were, within the inexperienced DMA Design team had paid off. Critically, it was met with mixed reviews however these were quickly overlooked by the storm of controversy the game stirred just days after hitting store shelves. Its violent nature was decried by much of the news press and politicians – at its height, the controversy was discussed in parliament. I ask Baglow if he or the team took any of the backlash personally.

“No, not at all,” he says. “In all honesty it was hilarious. We hadn’t set out to build the world’s most controversial game or even a slightly controversial game. All we were looking for was something fun. All we were looking for was something that worked and we thought was worth playing. We knew from the outset that there was something there – it took an awfully long time to drill down and figure out exactly what the hell it was, but we certainly didn’t set out to shock and offend and upset humanity.

“When we were starting to get denounced in the houses of Commons and Lords, when the press were up in arms, we were amused by it. Sorry, I should say bemused by it. We were like, really? You think this is bad? Because it’s all top down – there was no actual real cut scenes or animation or anything – and everything was implied. At every point it was just text that served to tell you the kind of things that were happening, the kind of things that were going on. It was absolutely not a game where we set out to try and be provocative.”

Given the process of evolution Grand Theft Auto has endured in the intervening years, both technically and critically, it’s hard to imagine how what is ultimately a text-based, top-down game with crude aesthetics at best, managed to cause such outrage and furore. Speaking to evolution, Baglow points to this as key to understanding the DMA team’s process at time.

“The team didn’t set out, nor did the company, to reimagine the impossibilities of a sandbox game,” he says. “It was based upon the fact that Mike Daily had made a quite clever wee game where you could see the sides of boxes and some clever sod said, ‘well, hang on – if we stick a road as the background you’re looking top-down at buildings.’”

So they built a city, they made it so you could run around in it, then drive in it – it was a series of logical steps working within technical constraints. It never rains in Liberty City because weather effects would’ve required processing power that the underwhelming engine didn’t have.

Had Grand Theft Auto been canned prior to its release Sam Houser wouldn’t have bought over DMA, moved the company to Edinburgh and branded it Rockstar North. That’s not to say Grand Theft Auto as an open world city-roaming, underworld-thriving concept wouldn’t exist today, it just wouldn’t exist in its current guise.

As of August last year, the Grand Theft Auto series has sold over 220 million copies. And that started with the original in 1997, a game which was almost scrapped.

If you’re a fan, be happy it wasn’t.

Gouranga.