Signposts are wondrous things, when you think about it. Especially ones that point in all directions. They are laconic guides, yes, but not pushy ones. Signs are spaces, cities, even worlds, in microcosm; they rescue lost explorers mid-adventure and herald the promise of more, the name of each destination teasing infinite possibilities, bewitching yarns, and the electrifying thrill of the new.

For me, now, it’s the latter: the names Cascadia, Fallbrook, Amber Heights, and Stellar Bay gleam in inviting neon lettering, bright against the blackness of space, as I contemplate a signpost on the planet Monarch. My one-hour sojourn into The Outer Worlds begins at the Fallbrook Crossroads, and I can stroll at my own pace to whichever spot I please, or none. I am unburdened by any active quest or objective, without the veiled hand of a developer thrusting me towards an orchestrated set piece.

I’ve heard stories about Fallbrook. Something about the production of questionable pork from mutated pigs. I’m going to skip that for now, thank you very much. Cascadia sounds a bit hectic for my liking, so, eventually, I turn right towards Amber Heights. I’m not sure if it’s that the name of my destination reflects my current state of indecision but I set out on my own, anarchic path, and I’m soon knee-deep in Mantiqueen gore.

My demo starts me at level 11, which means I already have some tasty, death-dealing toys to wield. My Dead-Eye AR relieves targets of their innards from a distance with a pleasing pop, and my heavy machine gun discharges a hellish, leaden tornado toward any enemy or explosive barrel unfortunate enough to be in its way.

Manti-gore

It isn’t exactly Doom, but The Outer Worlds’ gunplay does enough to make the use of heavy or energy weapons tempting. Varied enemy behaviour means fights are far more than shooting galleries, too: insectoid mantisaurs protect their abdominal weak spots with spindly limbs, and some human foes will charge at you to melee, while others snipe at you from a distance.

I like to think that cunning, sneaky types like me are above simply bashing foes about with blunt instruments, but melee weapons are also rather satisfying to use. Not only can you hold left mouse down for a charged overhead attack, but it’s even better to hold your attack button down after a single swing, which initiates a devastating second swipe. As I gaze with manic satisfaction upon a freshly-produced carcass, I’m reminded of my dad’s advice to keep my golf swing to a controlled one-two rhythm. Except that time I was going for a hole in one, rather than one hole on my target’s bonce.

If your arms get tired, you can let your sharp-tongued companions do the murderous dirty work for you – and you can make them even more effective if you invest in a leadership-focused build in The Outer Worlds. With me I have Parvati and alcoholic big game hunter, Nyoka. You can find such friends with whom to share your adventure early in the game, and they are certainly useful in a scrap.

Nyoka’s special attack sees her somehow drown the sound of her gargantuan machine gun with her own blood-curdling battlecry, and Parvati introduces her targets to her electrically-charged hammer for an irrepressibly fun game of shock-a-mole. Each assault features a gratifying bit of slo-mo animation that, while emphatic, could get repetitive if you stick with the same buddies for too long.

Tactical Time Dilation (TTD) also tweaks the pace of combat. Developer Obsidian’s answer to V.A.T.S in Fallout is much faster, which means a bit of forethought is required before you hit Q.

While it was possible to initiate your Vault-Tec Targeting System and then decide how to most effectively dismember your enemy, TTD doesn’t give you that luxury. You can use your tactical nous to cripple, blind and execute, but it’s not quite as S.P.E.C.I.A.L. as its inspiration.

Amber Warning

The game responds to me. After I take too much damage from a group of overgrown chameleons called Raptidons, I’m offered a perk point if I accept the Raptiphobia Flaw, which makes me weaker to them. I decide to embrace a new identity as a formidable anti-hero with a crippling fear of lizards, just because I can.

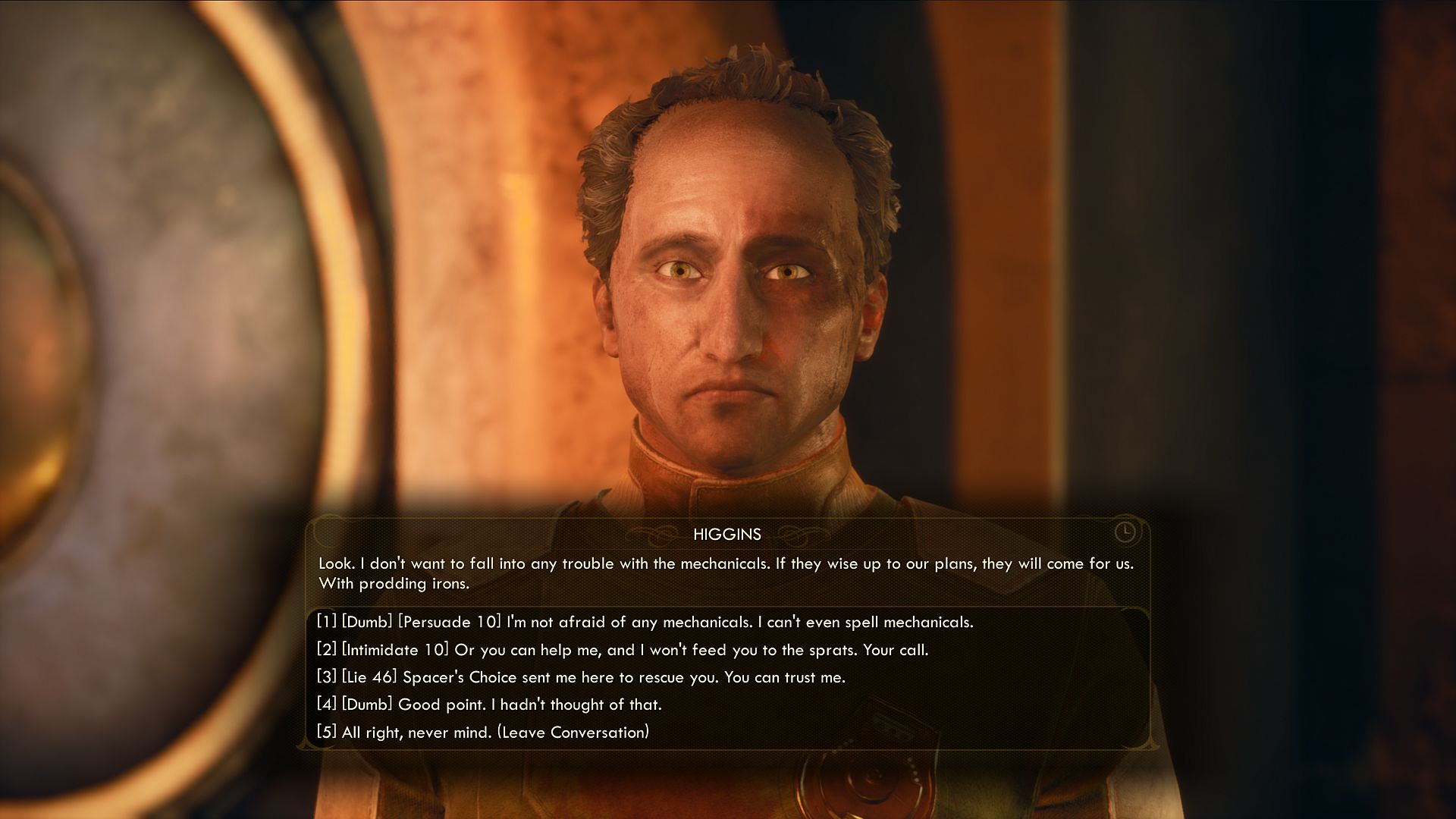

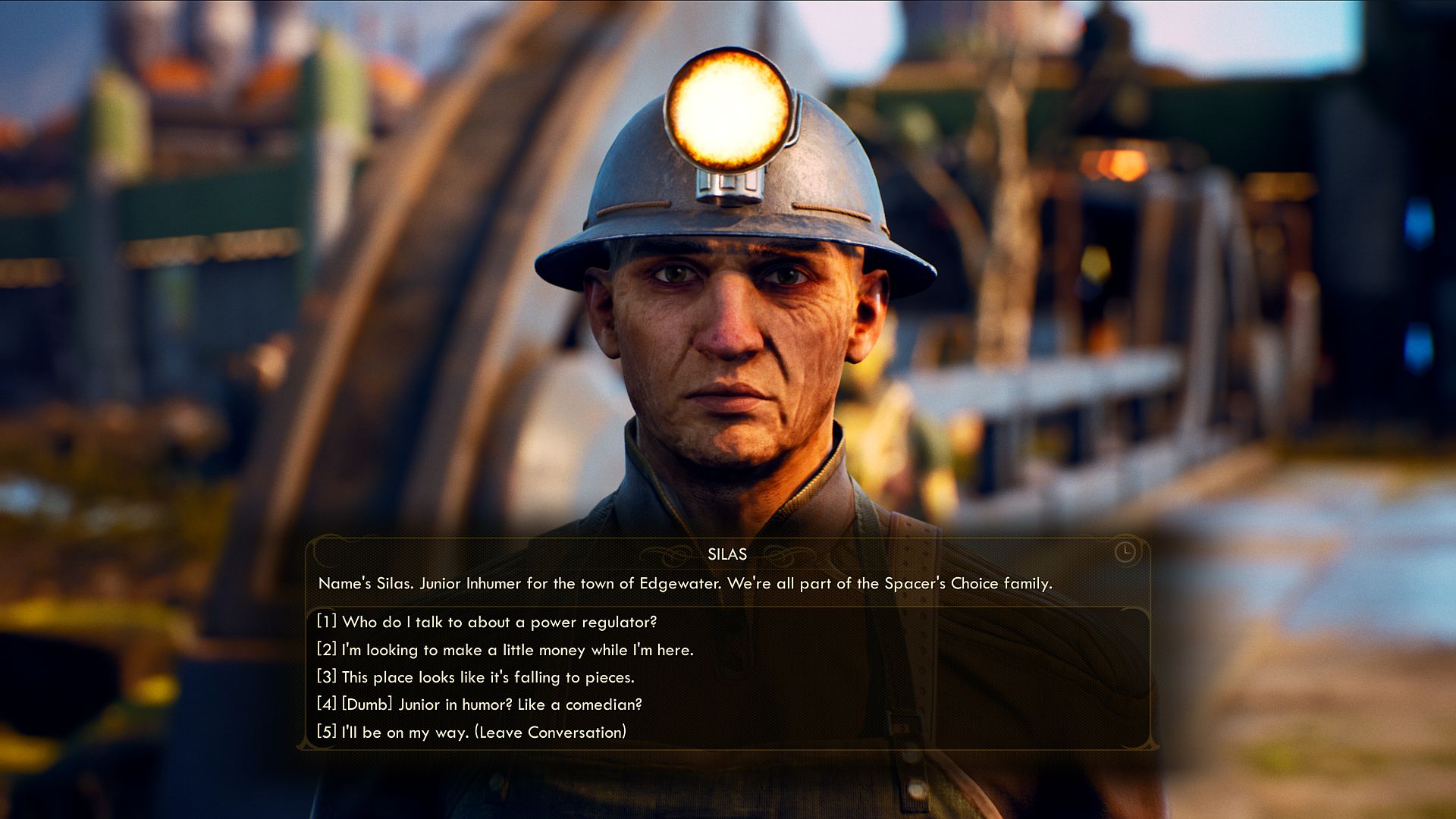

I walk on through gurgling swamps and towering fungi caterwauling with colour – it’s like an irradiated Vvardenfell. When I arrive in Amber Heights I look for ways to role-play a bit, to see what the game’s systems have in store. I find the local bar and claim a few five-finger discounts on booze. When my sneaking skills are found wanting by a nearby guard, I can lie my way out of it, or pay a fine. But my next experiment involved the entire population of this forgotten backwater.

Reader, I killed them all. Well, ok, I tried, and the populace didn’t take kindly to it. The game returns my brutally butchered body to a recent checkpoint. But, as I found out in my interview with Obsidian’s senior designer, Brian Heins, had I been successful in my attempted massacre, I could have carried on just fine. One of the team’s producers behaves in this psychopathic way at all times, I’m told: they completed an early build of the game by killing everyone they met, including quest givers and potential companions. Talk about being a lone wanderer.

Equally, it’s also possible to play as a pacifist. But while you can ‘rub everyone up the wrong way’, like me, you can’t please all the factions you come across: there will always come a point where you have to make a difficult decision or side with someone’s rival. This reputation system eventually informs the two main endings in The Outer Worlds, one of the many ways in which the game echoes Fallout: New Vegas’ multifarious powers jostling for supremacy in post-nuclear Nevada.

Out of this world

I may have only had an hour with The Outer Worlds, but in that time I struggle to find its limits. They do exist, of course; it doesn’t feel as if it matches the scale of a Fallout world. The quests I undertake seem short and sweet, and between the main areas – which are diverse and rich with personality – the smaller ones don’t share the same intrigue. It’s not a fully seamless open world, either, but at least the wait to enter each main location is ameliorated by lavish, BioShock-style art deco loading screens.

These are minor drawbacks I’ll willingly accept for The Outer Worlds’ exhilarating freedom. Monarch is a perilous, caricatured vision of our own planet, but as soon as I set foot on it, it already felt as if it were my own. Not since my first visit to the tree-filled tundras and sky-piercing mountains of Skyrim have I felt so enlivened by possibility.

I can be whomever I want, go in whichever direction I see fit, kill anybody that suits me, and embody the role which excites me the most. Every decision feels neither wrong nor right, but mine. After mere moments with the game, it feels as if it’s moulding to my input, like dystopian clay. I may not spend as long on a single playthrough as the most grandiose of RPGs on PC but, in The Outer Worlds, I’ll be living numerous lives, each utterly unrecognisable to the last. Every unfamiliar horizon unexplored, dialogue dilemma posed, and perk point unspent yields further stories ready to be written, and I’ll be savouring each and every one of them.