If you’re familiar with The Witcher Netflix series or the original short stories, you’ve no doubt come across the concept of ‘the lesser evil’.

This is a phrase Geralt hears upon entering the town of Blaviken, where a group of bandits led by a princess named Renfri are locked in a stalemate against a Kovirian wizard called Stregobor. Both parties try to hire the Witcher to kill the other, arguing that helping them would be the lesser evil. However, Geralt chooses not to intervene until he absolutely has to. He pays the price for his hesitation, as it leads to the incident that earns him the nickname ‘The Butcher of Blaviken’.

This story is the blueprint for The Witcher’s discussion of morality, with Geralt attempting to remain impartial in a world that frequently forces his hand. Though The Witcher draws on classic fairy tales, the morals are never quite so black-and-white, with monsters coming in many different shapes and sizes. This approach isn’t limited to the books or the TV series either, but is fundamental to the design of CD Projekt Red’s trilogy of games.

One of the most interesting examples of this occurs in the Outskirts of Vizima in The Witcher 1. Geralt is told about a mysterious hellhound that is plaguing a nearby village, with the locals blaming the beast’s appearance on a travelling witch named Abigail. At first, he tries to remain neutral in the face of these escalating tensions. But when an angry mob appears and tries to execute the witch, players can finally decide whether to intervene or stand aside.

Much like in the source material, there is no clear right or wrong answer here – there’s enough evidence to infer that either party could be at fault.

For example, Odo, a rich merchant and one of the more influential members of the mob, blames Abigail for the death of his brother, claiming that she bewitched him to commit the evil act. But that doesn’t quite explain how Odo was able to overpower his brother, who was much stronger than him, or his suspicious behaviour regarding the Echinops growing in his garden (a type of carnivorous plant that, according to the bestiary, only sprouts in places where terrible crimes have been committed).

The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings explores this theme further. Geralt starts the game in the reluctant employ of King Foltest as a direct result of foiling an assassination plot at the end of the first game. However, when a group of assassins, employed by Nilfgaard, kills Foltest, the Witcher is implicated in the crime and must hunt down them down to clear his name. Here the monster slayer again finds himself in a compromised position. Although he is clearly acting out of self-interest, his actions will undoubtedly have a larger impact on the world, helping to secure the rulers of the Northern Kingdoms against the Nilfgaardian plot to destabilise the region.

Perhaps nowhere is this struggle more apparent than in chapter two of Vernon Roche’s path, in which the Witcher is asked to choose whether to let Roche kill King Henselt, after the ruler murders the commander’s men.

If Geralt allows this to happen, he will be responsible for weakening the kingdom of Kaedwen, clearing the way for other kingdoms to take advantage. But if he lets Henselt go there’s a chance that he will escape punishment and commit even more violent and destabilising acts. How you react will depend on your outlook. Do you say nothing and turn a blind eye to an act of regicide? Or intervene and risk being responsible for greater torment?

These moral dilemmas are what make The Witcher games so fascinating to play, and The Witcher 3: The Wild Hunt is no exception. Its quests routinely put players in unwinnable situations, in which neutrality simply isn’t an option, but ‘the lesser evil’ still has wide-ranging consequences for all involved.

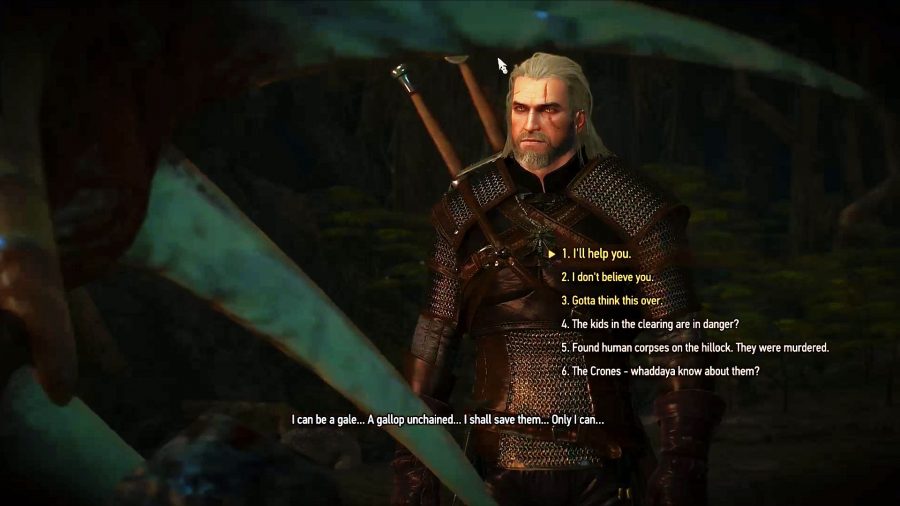

For example, in The Whispering Hillock, you will encounter a spirit who is trapped inside an ancient tree. The local ealdorman asks you to kill it, holding it to blame for a spate of deaths in the village of Downwarren. But it turns out the spirit is an enemy of the terrifying Crones of Crookback Bog, and it warns you that if you kill it, there will be no one to save a group of innocent orphans from the Crones’ gruesome designs. Either way, there are dire consequences from whatever decision you make, with Geralt unable to save everyone and having to weigh up his options, like a horrible trolley problem.

Geralt is expected to be a dispassionate, stone-faced killer – a supposed side-effect of the witcher mutations he went through as a child – but this is never truly the case. He is constantly drawn into conflicts that are much bigger than himself and forced to make impossible decisions.

Questions of morality – of knowing the right way to behave – have fascinated philosophers for millennia. Today, these exact same questions inspire the Witcher community into the same debates. With the Netflix series having inspired a surge of demand for both the books and the games, The Witcher and its nuanced approach to morality is as relevant as ever, more than 30 years after the first short story was published (1986), and 12 years after The Witcher 1 released (2007).