For a while, This War of Mine felt like a refugee tycoon game. I’d scavenged enough medicine to make sure everyone was healthy. My characters had warm, dry beds and freshly-cooked food. Suddenly, war didn’t seem so scary. This siege was turning into an adventure in self-reliance, a kind of wartime Walden.

Then I couldn’t find food for two nights in a row, and some thugs came to our hideout and hurt Pawel before stealing our supplies. Once again we needed medicine we didn’t have. The food ran out and suddenly everyone was tired and slowly starving.

That’s why I found myself breaking into another family’s home one rainy night, to steal food and medicine from another group of people not unlike my own. My scavenger, Katia, got caught rummaging through their kitchen.

There wasn’t time to think. I just want straight at this middle-aged husband and father and started kicking the shit out of him. “Why are you doing this to us?” he pleaded.

Because my people were going hungry, and I was out of options. It was them or us.

“From the beginning, we thought this game would be a perfect tool,” explained 11 Bit Studios’ Pawel Miechowski. “You’re not a spectator. Your choices decide how the narrative goes. And in such cases, a game may be the perfect tool to speak about important things, because it does not force you into a moral position. It gives you the ability to make your own moral choices.”

This War of Mine is a wartime survival game. Most of what you do is mundane: scavenge, trade, build, cook, and rest. But day-to-day survival is so fragile that it soon transforms these simple acts into moral choices.

I haven’t really found the contrived, intergalactic “Dear Abby” moral quandaries I came to associate with Mass Effect, nor the simple “good vs. evil” binaries typified by games like Bioshock. This War of Mine takes place in a chaotic moral universe perched on the edge of survival and starvation. A good deed may be rewarded or it may be punished. Maybe nothing will happen. The meaning of your choices is down to you and your circumstances.

“It’s driven by the fact that people actually face really hard moral choices, and nobody is freed of those. Sooner or later, everyone faces a situation where you have to sacrifice someone in order to save someone else,” Miechowski said.

“If you imagine yourself in such a situation, I believe some people will try to stay clean. But it’s extremely hard. We want people to wrestle with such a heavy topic, exactly because it’s the proper way of talking about this topic. Surviving wars. What is war? It’s suffering of regular people, it’s not just military battles of tanks and airplanes.”

This War of Mine never feels preachy. You might not be a soldier in this unnamed conflict, but neither are you and you characters innocents. Your foremost goal is survival, and you can’t do that just by tightening your belt and hoping fate throws something in your path. And if you do decide to take the moral high ground and set limits for what you’re willing to do in this besieged city, then the odds are very good that line in the sand is going to cost one of your characters their lives.

On the other hand, your characters themselves are not simply survival machines. In one game, a young woman raced up to our shelter and banged on the door. She desperately needed medicine, she said, because her mother was sick and wasn’t getting better. Did we have antibiotics?

We did have a course of antibiotics available. But they were also incredibly scarce, and we’d only just cured another character of an illness a few days earlier. I could have given this girl what her mother needed, but I didn’t feel like it was a smart decision. The girl was an NPC, and her mother just an abstract concept. They weren’t “mine.” So I turned her away.

Instantly, every one of my survivors picked up a new trait: “sad”. I didn’t know how to cure it.

Home Sweet Home

“From the first day, we knew that we had to find a middle way, so to speak, between the topic and the fact that it’s still a game,” Miechowski said. “It needs to be engaging. It needs to keep you, maybe not entertained, but thrilled. You have to dig into it, right?”

And this is the weird thing about This War of Mine: it makes being a refugee kind of… fun.

In many ways, This War of Mine is like a wartime Agricola, a popular boardgame about subsistence farming in premodern Europe. You can make real gains in terms of prosperity and comfort, but you have to carefully manage your resources or basic survival will become a problem. Except here, you’re also at the mercy of events and the reality of diminishing resources in a war-torn city.

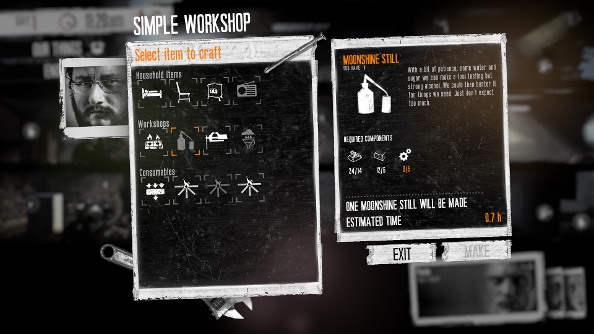

When the siege begins on Day 1, your first priorities are bare survival. You need food, first-aid supplies, and simple tools to help break into houses and build necessities like beds and wood-burning stoves. Those concerns never totally go away, and occasionally become acute.

But there are also creature comforts and efficiency improvements to be made. With enough materials, a simple work bench can become a fully-equipped carpentry and metalworking shop. That crude stove can burn less fuel and turn out more food if you lavish it with some extra upgrades.

And suddenly you might be in a position to thrive. You won’t need so many resources just to keep your head above water, and you can even start building things like comfy chairs and lanterns so that you can maintain a semblance of civilized life. That will help your characters as well, giving them physical and mental refreshment to help them endure their circumstances.

“From the design point of view, we were looking at [this game] as a perfect tool to talk about a serious topic, and yet [one that] used the language of games. Narrative tools, gameplay tools, rules of the game so that everything that is behind the mechanics makes it an engaging game,” Miechowski said.

That girl who came begging for antibiotics was one such event, but another type of event is a bandit raid on your shelter at night. If you’re not well-fortified and guarded, you could end up getting pillaged and your characters injured in the raid. Suddenly all those gains you made are gone, and you’re right back to hand-to-mouth survival.

The other problem is that the city is not a wellspring of infinite resources. As you visit locations during the night phase of the game, when you can send out a lone scavenger, you deplete them of items. Raid a house on Day 2 and take all the food? Then that house isn’t going to magically supply you with food on Day 5. You have to go elsewhere.

Those new locations get more and more perilous and complicated. Some are crawling with paramilitaries, while others are occupied by survivors not unlike yourselves. Some places have refugees you can trade with, so you have to decide what goods you want to send out with your scavenger.

And sometimes, when you have nothing to trade and no more margin for error, you have to steal from other people who were just trying to get by.

In extremis

Popular media tend to deal with the breakdown of law and order in terms of post-apocalyptic scenarios. The Hobbesian state of nature is always near, fiction likes to tell people. It’s just a zombie uprising, plague (and the always popular zombie plague), or natural disaster away.

That’s at once a very dim view of civilization and a very optimistic one. It says that there’s only a thin veneer between the person you think you are and a feral, desperate killer. But don’t worry, because things could never get so desperate unless the world were ending.

This War of Mine isn’t quite so extreme. For the Polish development team, and many of their Eastern European neighbors, civic collapse is not some distant, unimaginable doomsday scenario. It’s something that occurred within living memory, and still occurs today in countries where crisis once seemed unlikely.

“All of us had grandmothers and grandfathers who survived the Nazi occupation, and then Russian occupation during the Second World War,” Miechowski said. “And in Warsaw, actually, there are still many people living who remember how the city looked during and after the Uprising. When the city was completely destroyed, and people were trying to survive despite all the military action around them. …[Another colleague who] was with me at Axe Grind Studios, his grandfather survived the Siege of Leningrad during the Second World War. So she doesn’t like to talk about it much, but he shared some really thrilling memoirs with us.”

The Balkan wars of the 1990s also provided a lot of inspiration. One article the team referred to a lot was called “One Year in Hell”, which has itself become wildly popular among survivalist and “prepper” communities. Its provenance seems dubious (and being co-opted by fringe communities like hard currency enthusiasts and doomsday preppers hardly helps) but it does read like a design document for a wartime survival game.

But that article just provided 11 Bit with a spark of inspiration. From there, “We made quite a research effort,” Miechowski said. “We’re still doing it. Looking for stories and memoirs from people who survived different sieges…. A really good book was Besieged: Life Under Fire on a Sarajevo Street by Barbara Demick.”

This War of Mine starts with two assumptions, then, that set it apart from countless other apocalyptic video games. First, it says that just about anyone could find themselves in this situation. It’s not a game about hardened badasses lone-wolfing it through war, but ordinary people who thought their lives would be about anything but this.

The second assumption is that the war will end.

Survival with a cost

“At some point the siege is over. If you can make it with one person alive at the end, you’ve made it,” Miechowski said. “However, the length of the process in unknown to me, because it is randomly generated.”

That last part makes it harder to gauge how you should play. You might go into ruthless survival mode, only to discover that the war ends sooner than you thought and you kept people from medicine and food for nothing. Or you might find yourself in an endless nightmare siege and start bitterly regretting not letting the elderly member of your party die when he got sick, because he consumed precious resources you could never recover.

Survival might be the only goal for the player, but it’s not the only goal for the characters in the game. As they are forced to be colder and crueler, it takes a toll on them, and Miechowski says their morale can have surprising effects later in the game.

So I wonder, if I had ever finished that game where I started robbing other refugees to keep my little band from starving, whether my characters would have followed me all the way down that road.

Or maybe they’d have cracked under the strain as I discarded civilization and mercy in the name of survival. As a player, I felt like I was making the right decision. My stealth-banditry didn’t work out, so I beat someone up and looted his house, and my group had food to eat again.

This War of Mine leaves me in a weird place halfway between the desperation of my characters and their circumstances and the cold calculation of a strategist. I was able to justify an awful lot because I was playing a resource maximization game. My characters counted, and nobody else did.

But my characters were still programmed to react like civilized human beings. They were reporters, footballers, IT professionals, and retirees. They came from a world where you had a community and a society and you didn’t have to worry about your neighbor cutting your throat while you slept.

Implicit in This War of Mine is that, once this war ends, people have to live with what they did. They have to remember the people they didn’t help, the things they stole, the compromises they made. They forced me to ask whether there might be a price for life that isn’t worth paying. Their deepening sadness forced me to consider whether there were other choices, and if I wasn’t just too callous and paranoid to explore them.

This is the thing I love about This War of Mine. It doesn’t offer any clear answers. A war arrives and it imposes choices nobody should have to make. Then it asks whether your characters would want to live with them, because they may not be able to survive without them.