This War of Mine is a game about war, obviously, but without the explosions, thousand-high body count and glorification that normally come parcelled with games that show battles at the ground level. It’s a 2.5D survival management game about the toll of conflict, where complications and mundane, relatable concerns take the place of the awkward glamour usually associated with war.

Finding food and medicine, not fighting, becomes the focus. It’s a goal that can only ever be temporarily achieved before the fridge and shelves become bare and it’s out into the wild, war-torn city once again to search for something, anything, that will aid the band of survivors whose lives the player protects.

And protecting them sometimes means breaking them.

Bruno was dying. A serious wound – along with sickness, exhaustion and hunger – had forced him to bed, where he lay, almost motionless, praying for the end to come. To the group of three other survivors who lived with Bruno, he was their rock. His loss would be world-shattering.

It doesn’t take much for a survivor to reach death’s door. A botched scavenging trip where they end up fighting militia, a night-time raid on their home, a simple sickness that escalates due to a lack of medicine – oblivion is always lurking on the peripheries of the game.

An ex-TV chef, Bruno was always there to make dinner, and always had time to lift the spirits of someone who had just seen too much of the misery that permeates throughout 11 Bits’ deeply harrowing game.

It was a turning point, the catalyst that would dramatically change the tone of my first survival attempt. It was when I decided to transform the household, from a group of survivors into a band of predators.

Boris was the strongest of the survivors. A fireman before the war, he was tough even he was slow, and could carry significantly more supplies than anyone else. So that night, with Bruno bleeding out on his bed, I sent Boris to a nearby garage. Only one survivor can go on trips outside at a time. A father and son were holed up there, and we’d traded with them before. Trade was not the point of this visit, though.

The son opens the door, expecting to do a bit of bartering. Instead, he gets a knife in the gut. Hearing the commotion, his sick father leaves his room and witnesses his son’s final moments. Then his head gets caved in as Boris crushes him with a spade. It’s awful.

Combat in This War of Mine is unpleasant. Simply clicking on a person while a survivor brandishes a weapon starts an attack, but it’s fiddly. Sometimes the survivor just walks over to their foe, or past them, and then gets stabbed in the back. Sometimes they miss, because the RNG gods weren’t on their side. Part of the unpleasantness is clearly by design – fighting is dangerous and should be avoided. But the other part of it is because of bad design. A combat system can be competent without being empowering; it doesn’t need to be a bit rubbish to emphasise that the survivors are not soldiers.

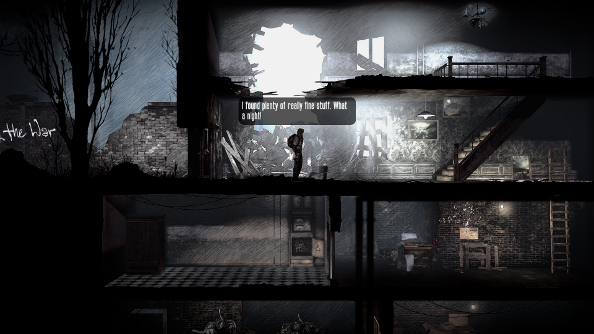

After murdering the garage duo, Boris filled his bags with loot and hoofed it back home, where he proceeded to plonk himself down in the middle of the hallway and cry. He was broken. It’s rare for a character to not be at least sad as things look more and more grim.

Before the war Boris rescued people every day, and with a few clicks, I’d turned him into a murderer. I didn’t see any other option at the time, though. The group needed medicine, something had to be done. As he sat there, not moving, a shell of a man, I wondered if I could have tried harder to find an alternative. But all I could do was try to make him feel better.

Fulfilling addictions like tobacco or coffee offer a temporary reprieve from the misery, but those supplies are hard to come by. Eventually, after getting all the necessary components from other buildings and through trade, it’s possible to build little gardens, allowing the survivors to become a bit more self sufficient.

Even sitting down on a comfy chair with a good book can help cheer people up. But that comfy chair must be constructed from materials that might be needed to build other important objects, like water purifiers, or secure the house by boarding up windows and gaps in the walls. And books can be used as fuel, and might better used that way, to keep the cooker running and the heater warm.

Whenever anything is consumed, it’s a massive sacrifice. That stale tobacco that dying Bruno so dearly wants to smoke, because he’s a bit depressed about the whole fatal wound thing, could also be used – along with other items – to barter for medicine. But if Bruno becomes so depressed that he ends up catatonic, like Boris when he returned from the garage, then the medicine is useless.

It’s a tightrope walk all the way through, with characters just surviving, only needing one small thing to go wrong for everything to fall apart.

Things never improved for Bruno, Boris and their two fellow survivors, Pavle and Marko. While the others attempted to talk to Boris and get him out of his broken, self-loathing state, Bruno died in his bed. The next night, a hunt for food went south and Marko didn’t make it home before dawn. He was out in the warzone in broad daylight. And with Pavle left to defend the house alone – Boris was in no state to help – he ended up seriously wounded when raiders burst in and shot him.

Boris hanged himself the next day.

This War of Mine is purposefully vague. The war is happening all around the survivors, but few details are offered about it. Similarly, characters are mostly blank slates, with small backstories, vices, skills and only a small glimmer of personality. Yet it’s affecting all the same. There’s no deep characterisation or long discussions, this isn’t The Walking Dead. But the horrors they go through make them vessels for stories.

There was the time where Pavle risked everything to help a pair of children take their mother to hospital, because he was partially to blame. They had asked for help earlier, just some medicine, but Pavle had refused – his friends needed it more. He was trying to make up for that. And there was that one glorious day where Bruno cooked a meal for everyone, and they drank coffee, smoked and then all had beds to crawl into when it got dark. Those rare moments of quiet, or where the survivors are actually able to help someone, are starky juxtaposed to the unrelenting fog of misery that hangs over the game.

While there’s an end point, where the war finally ends, after a cold winter and countless trials, it often seems like a fantasy, a dream that will never happen. Things get worse and worse as the game goes on. Safe areas where once the survivors could trade for goods eventually get swallowed up by the conflict, either becoming too dangerous to travel to or filled with extremely unfriendly bandits.

Becoming just like the bandits doesn’t ensure success and survival, either. Characters can be equipped with guns and forced into killing whoever gets in their way, but the more aggressive they are, the more they become targets for retribution, putting the entire household at risk.

There’s nothing enjoyable about This War of Mine. Every moment is a struggle, and the reward for surviving another day is just more struggle. Every year we drown in games where square-jawed heroes slaughter hundreds of men without a thought passing through the big empty space in their skulls, and it’s fun and empowering, but it’s got nothing to do with war. Where they are effective at making us feel like a bad asses, This War of Mine is equally as effective at reminding us that war is not a hoot, that it’s horrible and destructive and that most of the people involved are not soldiers.

It’s hard to recommend a game that makes you feel disgusted or upset, but I’m doing it anyway. This War of Mine is great, it just asks a lot from its players.