I’ll be honest: Total War: Three Kingdoms hasn’t been doing it for me so far. And I get the sense that the community feels similarly – most of the posts on the subreddit are still about Warhammer.

While the Gamescom demo I got to play last year was a very pretty battle with a cool character duelling system, it was still ‘just’ a battle. The most transformative changes that Creative Assembly is making in the next historical Total War – the series’ first flagship entry in almost six years – are happening on the campaign map. Last week, I finally got to try them out in a 30-turn demo of Liu Bei’s campaign, and now I’m officially excited.

CA has been clear about the importance of Three Kingdoms’ characters right from the game’s announcement, but those characters are largely unknown in the West (unless you play Dynasty Warriors or have read Romance of the Three Kingdoms). The game rises to that challenge, taking every opportunity to show you who these people are and why you should care.

It wasn’t long before I understood Liu Bei. He’s the closest the Three Kingdoms has to a ‘good guy’ – his tone and vocabulary is noble, and if he expresses a concern, it’s on behalf of the people. He’s joined by his loyal generals Guan Yu and Zhang Fei, lending an appealing camaraderie to the early stages of his campaign.

Their personalities emerge in banter both in pre-battle loading screens, and during combat: when an enemy general taunts Zhang Fei with the line, “You’re a better drinker than a fighter!”, his retort is, “That’s no insult!”. Lad.

Liu Bei starts with no settlement, but thanks to his sworn brothers, his initial army is the game’s strongest. I chase the upstarts of the Yellow Turban Rebellion through the mountains, seize their iron mine with little difficulty, and contemplate my next move. This involves poking around several menus and the campaign map, which is a thoroughly enjoyable process, because Three Kingdoms is gorgeous.

As the new day/night cycle progresses, the warm golden hue of sunset yields to cool inky black, and traders light tiny lanterns to guide their way. Seasonal changes are more detailed than ever: you’ll notice foliage turn from lush green to ruddy brown, while leaves, snowflakes, and cherry blossom drift lazily across the world. Zooming into the map will subtly blur the background with new depth-of-field effects. China’s terrain pops from the earth, just as the Old World did in Total War: Warhammer, but here it’s smoother, richer, and more detailed – even the fog of war looks good, in a haze of grey cel-shading.

It’s worth emphasising this. My reaction wasn’t, ‘Huh, that’s quite pretty’, but, ‘I might have to rethink my views on how good strategy games can look’. It might spoil Total War: Warhammer III for me, if its tech can’t be brought up to Three Kingdoms’ level. It’s even convinced our videographer Keiran – who has no interest in strategy games, but a strong interest in all forms of visual design – to give it a try.

It was the sleek UI that sold him, as much as anything else. Art director Pawel Wojs explains that the team spent “maybe a couple of months” mixing different inks in different consistencies, filming how it flowed to create their own custom ink shader. It looks glorious, character menus and diplomatic negotiations emerging from an ever-flowing splash.

The new tech tree – named Reforms – is a lovely ink sketch of a literal tree, where nodes explode with rich, red cherry blossom as they’re researched. The game’s cinematics are also rendered in ink, and will not only introduce each campaign, but also pop up in-game to illustrate major events.

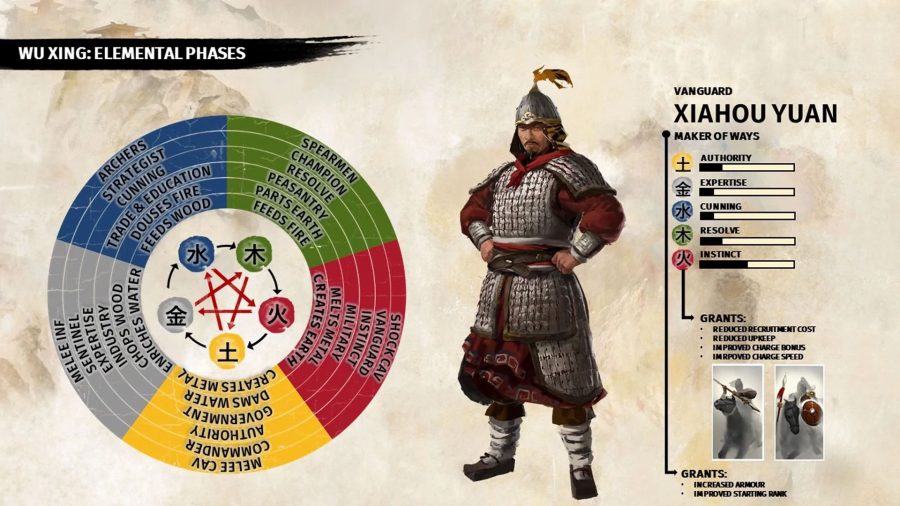

The UI is also the most obvious place to see Three Kingdoms’ depiction of Wu Xing – a conceptual scheme of five transitory elements, with positive and negative interrelations, under which various phenomena were explained in Three Kingdoms China. The UI will colour code character attributes within this system (Instinct, the fire attribute, is red) and Total War’s traditional scissors-paper-stone unit balancing fits it neatly, but you’ll see Wu Xing reflected in more subtle ways, too. Vanguards, the Instinct-based character class, will wear red clothing, and even the roofs of certain buildings on the map will correspond to their element.

As you might be starting to realise, Wu Xing runs through Three Kingdoms at every layer, from the physical to the metaphysical – just as was imagined at the time. It’s a beautifully elegant example of commitment to the setting, and it serves a practical purpose in explaining the game’s complexity through a visual language.

Because it is complex. The overhauled diplomacy and character systems suggest this may be the deepest Total War yet. Personally I’ve always felt that diplomacy is the system that, given such an overhaul, could benefit Total War the most, and I’m excited to see half a dozen interactions – often more – in each of its four categories in Three Kingdoms (war and peace, trade and marriage, alliances, and diplomatic treaties).

A deal in which I get an AI to pay me more than 600 gold per turn to sign what seems to be a mutually beneficial trade agreement suggests some tuning still needs to be done, however. And if there was a reason for the AI’s generosity, the UI – while gorgeous – didn’t show it.

Related: Brace for Total War: Three Kingdoms classic mode

Another example: Joe Robinson, of our sister site Strategy Gamer, said he had clicked a few times on a ‘plus’ button in a character’s info panel, thinking it was providing some benefit. The details of said benefit were unclear, as was the fact that each click cost him a couple of thousand in copper.

I enjoy Total War’s battles, but I confess to enjoying the campaigns even more. I like to build, to plan, and to optimise, and Total War offers many indicators of your progress from a minor power to a dominant empire: your place in the tech and settlement trees, the territory you hold, the armies you command. It looks like Three Kingdoms will embrace the journey of these games more keenly than ever.

There’s a new tree for you to ascend, the currency of which is Prestige. You’ll earn this by capturing and expanding your settlements, climbing China’s aristocracy as you go, with the chance to declare yourself Emperor – the campaign’s ultimate goal – awaiting at the top. Certain logistical capacities that are unlimited in other Total Wars, such as the number of spies, armies, or trade agreements you can maintain, are only unlocked when your faction is suitably prestigious.

Even your ability to project power across the map is limited by the Supply mechanic, returning from Thrones of Britannia. When an army is in enemy territory, its supplies will be steadily spent, and it will suffer attrition and morale loss when they’re exhausted. This sets a firm limit on your armies’ effective range and, thus, on the places you can conquer, adding another fathom of consideration to Three Kingdoms’ much-deepened diplomacy.

It might prove frustrating to have such caps on abilities you’d previously take for granted, but I’m excited by the potential that’s here to make Total War’s campaign layer even more strategically satisfying. Besides, it makes sense that a more sophisticated faction would have more sophisticated administration, and the Reforms tree offers some leeway – I unlocked two trade routes through Reforms while I was still on my first prestige rank.

In 30 turns with Total War: Three Kingdoms, my only complaints arise from UI optimisation and a strangely generous AI. I spent most of the time gawping at how pretty everything is and either enjoying, or imagining my future enjoyment of, the thoughtful and wide-ranging additions that have been made to the campaign.

Read more: March on the best strategy games on PC

Creative Assembly still has some opportunities to polish the game, and obviously our definitive review will go into way more depth than 30 turns with just one campaign. But if – like me – you were sceptical, now is the time to take notice. Total War: Three Kingdoms undoubtedly offers the prettiest campaign in the series to date, and it may well prove to be the best and deepest, too.