Empty cells. That’s not exactly what the unoccupied rooms at Daedalic look like. But open a door off the square of corridors that makes up their Hamburg HQ, and there’s a good chance you’ll be met by nothing but whitewashed walls and the memories of projects like Goodbye Deponia and The Whispered World.

The men and women of Germany’s premier adventure game developer are not numerous enough to fill every room of their offices – instead rotating between projects, filling fresh spaces with PCs and Doctor Who posters. But eventually they’ll return to those empty rooms, covering their walls with ideas and carpeting their floors with noise.

They’ve done the same to San Francisco’s famous prison – refilling its whitewashed cells with convicts, its visitor’s room with shrill family drama, and its lunch hall with the low murmur of illicit conversation. They’ve restored it to the way we might imagine it was 60 years ago, and planted the player behind the eyes of an inmate intent on pointing and clicking and puzzling his way off The Rock.

It’s probably the most traditional of the adventure games Daedalic currently have in development – but for a mechanical conceit that allows it beyond the walls of its no-chance security prison and onto the streets of ‘50s ‘Frisco.

Throughout 1954: Alcatraz, you’ll alternately control two halves of a young couple – Joe, jailed for armed robbery and suspected by his bunkmates of having stashed substantial ill-gotten earnings away on the outside. And Christine, his wife – an artist, writer and scenester with what Daedalic call a “highly flexible sense of ethics”.

Joe’s sentence is long, and both are acutely aware that they might spend their best years apart. They therefore take a hands-on approach to resolving their predicament – less hand-wringing and appealing to boards, more forging documents and hatching escape plans.

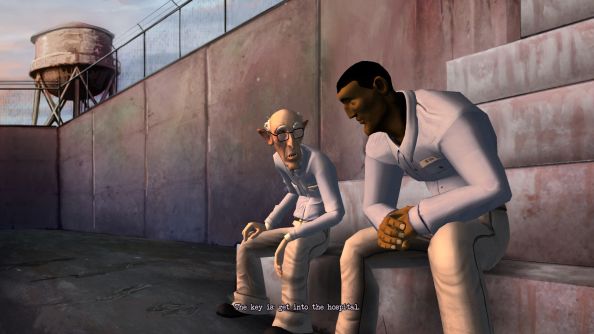

These aren’t natural born crooks, however. Joe has a straightforward manner that renders him instantly likeable – probably undeservedly. Combined with Christine’s dry wit and cultural nous, the pair recall Broken Sword’s George and Nico – capable counterparts in a life-threatening situation.

The two games don’t play dissimilarly – San Francisco’s scenes (or screens, in adventure genre terminology) are mostly static: locations to be scoured more than once for tools and clues.

But Alcatraz’s trick is to let you switch between characters at any point, rather than when directed to. Flicking between perspectives is a simple matter of pressing a button, functionally identical to Double Fine’s Broken Age – but Daedalic’s two worlds are rather more directly linked than Schafer’s.

Puzzles in Alcatraz are often solved from both sides of the prison walls. In one early sequence, Joe is locked away in solitary and Christine is required to work the warden to get him out. Meanwhile, Joe muses about guard patrol times and ‘taking a walk’ – suggesting that he too will play a part in the solution.

“In some cases, you get stuck with Joe and he has no way to get out. In other situations there’s something Christine needs from Joe, because he’s the only one who knows where the money is,” elaborates Daedalic designer Matt Kempke. “They have to rely on each other, although they don’t [physically] meet until a very important scene in the game.”

Tackling a problem from two angles is a mechanically intriguing prospect – though it seems Alcatraz will stop short of offering two possible routes to the same outcome.

Nevertheless, it’s a clever and simple workaround to that age-old adventure game problem – getting stuck with no apparent tools to hand. Switching from the island to San Fran and back again won’t solve your puzzles for you. But it will reliably open up the game with new challenges – letting the existing jigsaw jumble about at the back of your brain, where they’re so often put together.

What’s more, the back-and-forth will offer variety. Daedelic suggested that while Joe’s puzzles were most frequently of a technical, tangible nature, Christine’s were more sociable: requiring careful navigation of scenesters plus a couple of wiseguys – former colleagues of Joe’s who seem to know something about his missing cash, and who provide much of the game’s early sense of peril.

While the rock itself is no looker, Alcatraz is a quietly pretty game – easily readable and evocative. It began development four years ago under a one-man band in San Francisco – Gene Mocsy, co-writer of spiritual Monkey Island successor Ghost Pirates of Vooju Island. In the time since, it’s acquired two tandem teams (one at Daedalic, the other at San Francisco’s Irresponsible Games) and a modified Unity engine which hosts Daedalic’s own framework.

Joe, Christine and their co-stars are rendered in three dimensions, but judicious employment of thick, Walking Dead-style comic book lines sees them blend attractively with the 2D backgrounds. Kempke happily admits the influence of Telltale’s breakout hit.

“One thing that Gene started with is simply-structured models,” he explained. “If you then try to make them look nicer, you have to find some ways to not make them too realistic, but also not too cartoony, because that wouldn’t fit the style. The Walking Dead did strong [brush] strokes in the faces, and Alcatraz looks a little similar.

“The Walking Dead also tried to find a way to make it producible [in episodes], and not too heavy on the computers,” Kempke added. “So I think [Telltale] found a nice way, and our art team found a nice way to adapt Gene’s models.”

The comparison isn’t entirely apt. Though the player is occasionally called upon to make key choices (and ultimately determines the game’s ending), conversation in Alcatraz isn’t nearly so innovative as The Walking Dead’s tightly timed dilemma machine. Instead, it’s more reminiscent of BioWare’s investigative natter loops – providing the player with ample chance to hear old hints anew.

But the dialogue itself is uniformly top-notch – sometimes deadpan, sometimes hard-boiled, and all with a vitality about it enforced by the urgent setting. It’s also full of period swears.

“When you start with an adult-themed direction you want [the game] to stay true,” said Kempke. “I’m disappointed sometimes as a player when those levels are being switched. Like when you play a cartoony game that has a lot of humour and suddenly there’s a sex joke in it, and then you just imagine 50 twelve-year-olds who didn’t get the joke. In this case it would be just a little bit sad if we didn’t use the potential.”

The voice acting, too, is a cut above Daedalic’s occasionally iffy standards. Joe inspires confidence despite his footing in sinking sand, and Christine’s quickfire drawl betrays her intellect.

I’m not sure if the wider public drawn to the adventure genre by its recent revival has time for another in a year preemptively swallowed by stellar Telltale serials. But once they’re done with – deep breath – The Walking Dead, The Wolf Among Us, Broken Age and Broken Sword 5, then they might turn to this mongrel adventure. Which, like protagonist Joe, is self-confident enough to inspire confidence.