To many, videogames are a kind of medicine. I’ve read stories about people immersing themselves in Metal Gear Solid to get themselves through a bereavement, obsessing over grindy MMOs to help deal with the directionless unease of unemployment, or revisiting childhood favourites to find an emotional anchor during traumatic life transitions. I’ve read those stories, encouraged by the apparent restorative properties gamers have found in the medium – but I’ve never really identified with them.

Because, in my own experience, games have occasionally had the opposite effect during trying times. Like the week I spent playing Always Sometimes Monsters, fixing a pixel art deadbeat’s life while ignoring my own, almost identical, troubles.

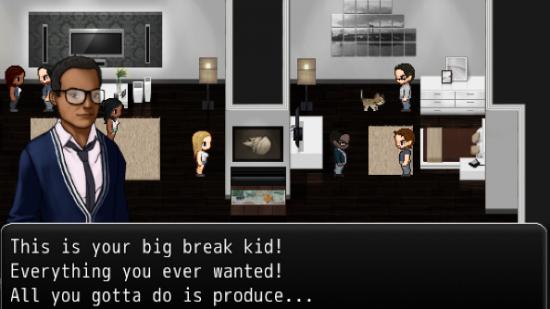

Back in February, I played the game for about 45 minutes – long enough for developers Vagabond Dog to foretell the trajectory of my own life for the next six months. I took control of Brick, named for reasons long since forgotten, sauntered through Larry’s shmoozy loft apartment party and shared his joy in securing that book deal. Brick and his girlfriend Rashawndra were on an upward trajectory, buoyed by a sizeable advance check. What a fortunate chap.

[There will be plot spoilers from this point on. If you haven’t played the game, go and do so before reading the rest of this. I’ll wait.]

In the fullness of time he isn’t such a fortunate chap, of course. The game quickly fast-forwards one disastrous year through Brick’s life: he’s split up with Rashawndra. He’s failed to follow through on the book deal, and he can’t afford to pay rent. Kicked out of his apartment, he wanders around Dubstown looking for a sofa to spend the night on and hoping to land a day’s work that’ll pay at least enough to buy a sandwich. Wow, Brick, I think. You done messed up. Leaving Brick at rock bottom, I stop playing and don’t think about Always Sometimes Monsters for a few months.

I start thinking about it again six months later, having split up with the girl I was with back in February, failed to follow through on a big break media job, and found myself briefly sleeping on a friend’s sofa in Hackney. Had I been watching my personal plot arc through the prism of retro visuals and cheery chiptunes, I’d have been inclined to utter a Wow, Phil. You done messed up of my own. The peculiar thing about hitting rock bottom IRL though, is that you rarely realise it at the time. You’ve always got plans, however tenuous, for clambering your way out of the hole.

I had a lot of problems to sort out. Big problems; the kind that keep you up at night. I needed to get proactive and enact those plans. What I did instead of that was play Always Sometimes Monsters. If I can get Brick out of this, I rationalised, I can do it for myself.

The gaping hole in that logic, of course, was that by getting Brick – an imaginary character in a videogame – out of his imaginary problems, I was not simply deferring but actually worsening my own. When you write about videogames for a living you’re never ‘unemployed,’ you’re just ‘freelancing.’ The thing about freelance work, though, is that you have to go out and get it, and when you’ve recently reneged on a full-time gig and are subsequently penniless, that means emailing every human being you’ve ever met on the off chance they want to pay you to write about Icewind Dale 2.

Playing Always Sometimes Monsters instead of doing that was literally costing me money.

It’s worth mentioning at this point that my life wasn’t an exact facsimile of Brick’s. I wasn’t in any real danger of sleeping on the street or dying of starvation. (Thanks, long-suffering family and friends!) I didn’t feed myself by fishing, or float any money on a sandwich-based stock exchange. I wasn’t planning on crashing any weddings. I have never met, nor am I ever likely to meet, anyone called ‘Darkeff.’

However, like Brick – and whatever you chose to call your protagonist – I don’t deserve any sympathy for my situation because we created them for ourselves. And our ‘to-do’ list was largely identical: find a way to pay the bills with our writing, heal romantic wounds, try to be a decent guy while doing so.

My unhealthy investment in Brick’s fortunes meant I fell for every one of Vagabond Dog’s traps. Remember the warehouse gig in Beaton? That endless conveyor belt of boxes forces you to wrestle with your work ethic; your willingness to graft for the things you want in life; to see the big picture.

The developer’s intent is that you give up after a few monotonous trips between the conveyor belt and the van, feeling a bit silly for sticking it out as long as you did. I shifted well over a hundred of those boxes. If I couldn’t put food in Brick’s stomach, how was I going to do it for myself? The only option was to persevere until I was certain, beyond a shadow of a doubt, I’d get paid. Meanwhile in the real world, my outbox continued to lay untainted by desperate feature pitches.

I was similarly single-minded in my desire to make it to Rashawndra’s wedding with a clear conscience, and that meant winning several boxing matches to earn some tires to upgrade a car to win a race that settled said car’s ownership in order to secure a lift to the wedding, because videogames.

My surroundings took on the appearance of a conspiracy theorist’s dilapidated apartment; scraps of envelopes with indecipherable scribbles (in fact, notes on the game’s wilfully unintuitive boxing control scheme) littered my periphery. I was a few lengths of twine pinned to a corkboard away from irreparable madness.

In the end, I made sure Brick got his happy ending. Essentially, I cheated. It was inevitable, really – having learned of ASM’s multiple conclusions I wasn’t about to leave anything to chance. I wiki’d my way back into Rashawndra’s heart, bailed Sam out, and turned my journal entries into a bestselling novel. Did I feel any better about myself? My life? Honestly, not really. I did feel ready to start climbing up out of that hole though, in the same way tidying your entire house somehow mentally prepares you for writing that uni dissertation.

I want to say finding a happy ending in ASM provided catharsis, or therapy. I want to say it eased my path back into the life of a functional adult who can pay his bills, manage relationships and sleep in his own apartment. In reality, it probably postponed it.

But just as Brick made money from those troubled journal pages, you’re reading an account of my experiences, which I’ve been paid to write. We both found a way to make it work.

Always Sometimes Monsters is a wonderful, thought-provoking game, one of the best I’ve played in 2015 – and I have absolutely no desire to ever replay it. In fact, as wonderful as Vagabond’s in-development sequel Sometimes Always Monsters looks, I’m not sure I’ll be able to play and enjoy that for quite a while yet.

I’m not saying games can’t be medicine – I’ve heard too much evidence, journalistic and anecdotal, on the contrary to argue that. I’m saying if you’re playing a game during a rough period, it’s not helping you by default. The medium’s greatest allure to me has always been the wholeness of its escapism, and there are times when escape isn’t the right prescription.