As a newcomer to games, you would be hard-pressed to guess what an MMO or roleplaying game was based on the name of the genre alone. But the platformer is among the most self-explanatory. They are, by and large, games about hopping between platforms. The joy of movement, the frustration of failure, and that moment of impossible buoyancy after you hit the jump key.

Related: the best indie games on PC.

They can be potent mood pieces, as in the uncanny horror of Limbo and Inside. Or, more commonly, offer a powerful dose of nostalgia, evoking the simpler games of yore. But even since the indie boom, commercial platformers still rarely present themes, allegory, or deliberate messages beyond the maxim ‘gotta go fast’.

Perhaps that is changing. Super Mario Odyssey, with its human-like citizens who tower above its cartoon protagonist, conveys the sense of adventure and strangeness inherent in travel. The End is Nigh, Edmund McMillen’s quietly-released successor to Super Meat Boy, is a gruelling meditation on pressure and expectation. And Celeste, the new game from the creators of TowerFall? Celeste is inescapably about something.

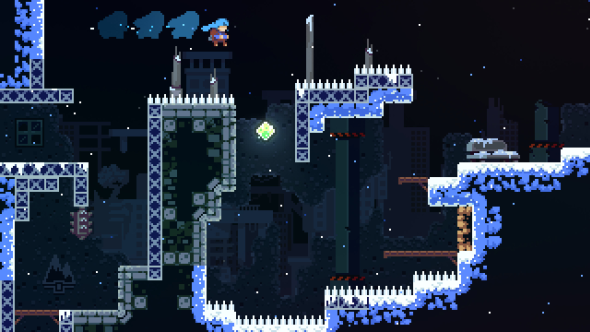

The protagonist’s name is Madeline. Celeste is the mountain she has resolved to climb in a platformer largely about vertical progress. You propel yourself upwards through a combination of wall-jumps, climbs, and ‘dash’ moves that fire you a short distance in a given direction. Madeline quickly loses her grip in a testing climb, and needs to make contact with a flat surface to recharge her dash – success requires you switch back and forth between her abilities, sometimes at speed. It can be tough.

Related: Explore the best platform games on PC

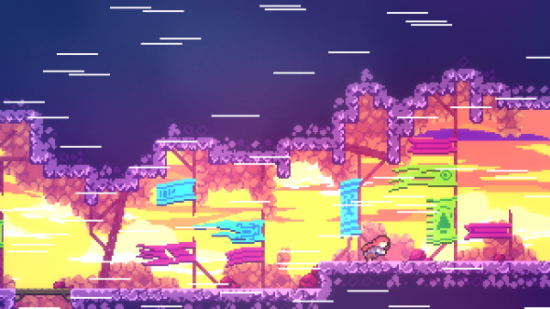

The mountain’s environments are in some ways typical of the genre – chunky and covered improbably in spikes. But even in pixely 2D, they are filled with recognisable real-world imagery. In the lowest reaches of Celeste, the screens are decorated with urban furniture: road signs and scaffolding. In one of its first challenges, a background billboard advertises a ‘MAN UP!’ energy drink. Another features a tiny-waisted bikini model, and asks: ‘ARE YOU BEACH READY?’.

The latter is starkly reminiscent of an advert plastered on the trains of the London Underground two years ago, which sparked horrified reactions on social media and was banned shortly afterwards by the UK’s advertising watchdog. In Celeste, it contributes to a sense that, despite Madeline’s determination, forces are working to undermine her self-confidence, dragging her down like the gravity on her upward climb.

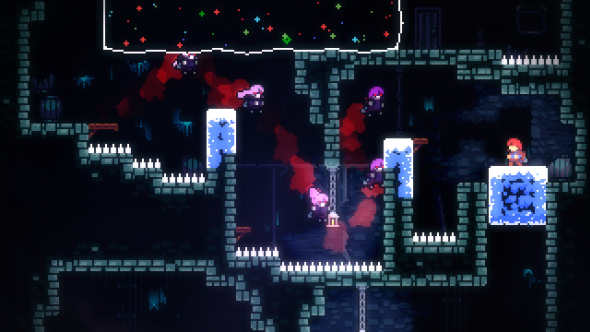

Early on, Madeline comes across a strange mirror, much too wide to be a comfortable presence in any home, and sees herself in it. Or at least a version of herself – palid and purple-haired, the colours inverted as if in MS Paint. The mirror shatters, and her self-image clambers out, a negative reflection that proceeds to follow her incessantly.

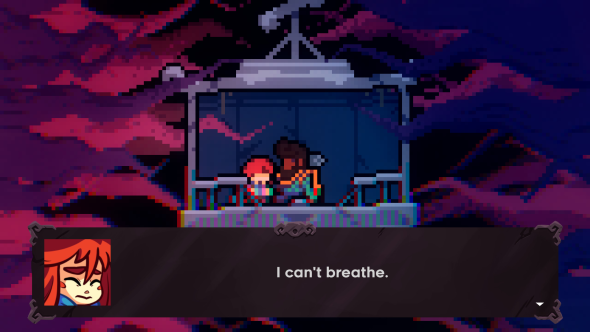

In one sequence, Madeline’s self-image chases in her exact footsteps – slowing when she slows, dashing when she dashes. It is a trick that has been used before to excellent effect in Mario, but never as a metaphor for a panic attack.

“You are many things, darling, but you are not a mountain climber,” Madeline’s self-image tells her. “I know it’s not your strong suit, but be reasonable for once. You can’t handle this.”

“That is exactly why I need to do this,” Madeline replies.

In interviews, McMillen has said he intended The End is Nigh to be uncomfortable for players who had their own issues with stress. But Celeste, by contrast, seems determined to invoke anxiety without inducing it during play.

The game borrows the micro-challenge structure McMillen helped popularise with Meat Boy a decade ago – throwing you sometimes extraordinarily difficult rooms to traverse, but never punishing you with a finite number of lives or a checkpoint further than a screen away. “Be proud of your death count,” reads a postcard addressed to Madeline in one loading screen. “The more you die, the more you’re learning. Keep going!”

Another postcard absolves you of the responsibility of worrying about Celeste’s fruity collectibles. “Strawberries will impress your friends, but that’s about it. Only collect them if you really want to!” The cards bear a Canadian stamp as if sent directly by developers Matt Makes Games, who are based in Vancouver.

Then there’s Celeste’s assist mode, which allows you to turn helping hands on and off at will: temporary invincibility, an extended dash, or even a slightly slower game. Whatever you need to get you through a tricky screen.

There’s something lovely about that – the sense that Celeste’s creators are too cognisant of the effects of anxiety to push it unnecessarily onto their players. It is especially refreshing in a genre that, even now, fetishises oppressive difficulty and upset. Not only does Celeste have a message, but it cares enough to deliver it warmly – as a supportive arm rather than a cruel reflection.