People love a good mystery. Not knowing, but needing to know, is a deep-rooted urge that compels us to keep experiencing mystery stories in the hopes that, by their end, all will be revealed. This is reflected in the mystery genre’s enduring legacy in media of all kinds – presented with a compelling question, we watch, or read, or listen on until we find out what exactly happened.

And until recently, detective games followed the same passive format laid down by older media. Mystery narratives in games behaved as they do in movies or books, unfolding chronologically as you progress through the plot. You never really got to interface with the mystery or try to solve it for yourself, which is a huge missed opportunity for an interactive medium.

Luckily, recent games like Outer Wilds, Telling Lies, Pathologic 2, and Disco Elysium are rethinking what it means to solve a mystery in a videogame, building their worlds around leads to follow, and pioneering mechanics that serve the player, enabling them to actually contribute to solving things for themselves.

Nonlinear gameplay is key to the recent mystery renaissance in games. Developers have learned to trust players with the tools to excavate clues and even story beats, which they’ve developed the confidence to hide to varying degrees. This forms the foundation of far more interesting game structures than a linear narrative would.

Take both Disco Elysium and Pathologic 2 as examples of games with more traditional structures, but which nevertheless give players enough freedom within them to dig into their secrets more directly. Both games set up mysteries to solve; Disco Elysium’s is an apparent lynching, while Pathologic 2 has the dual mysteries of your father’s murder and the cause of a plague that’s killing the local town.

To progress towards the endgame in both, you must progress through time, as like The Last Express, you are on a clock. But what you accomplish within those time limits is up to you, as each game sets up leads you can follow in any order, even going so far as having them expire after a certain amount of time. It’s the act of stringing together these leads that forms your experience with the games.

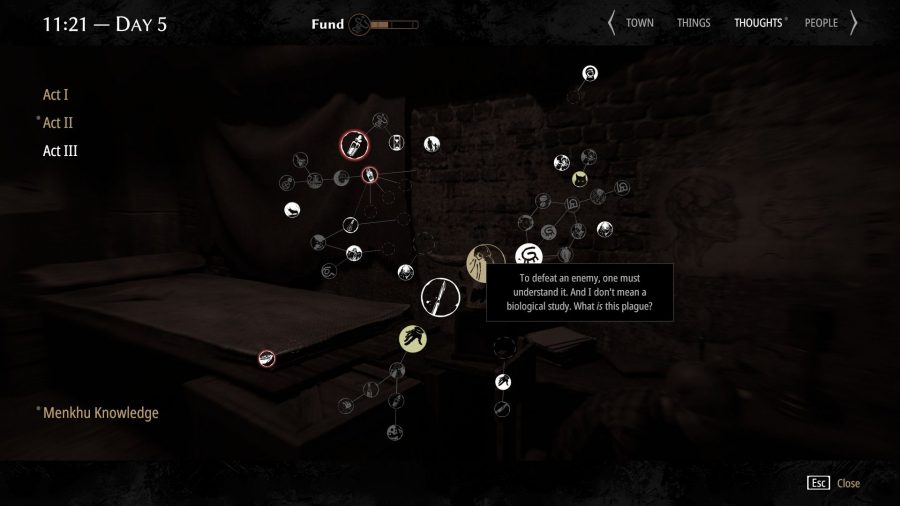

It also helps that games have got better at keeping track of your accomplishments. Pathologic 2 in particular includes flow charts that show the leads you’re working on, those you’ve already investigated, and how they connect. That way, you’re always clear about which leads relate to which discoveries you’ve already made, allowing you to focus on one or two facets of the mystery that pique your interest.

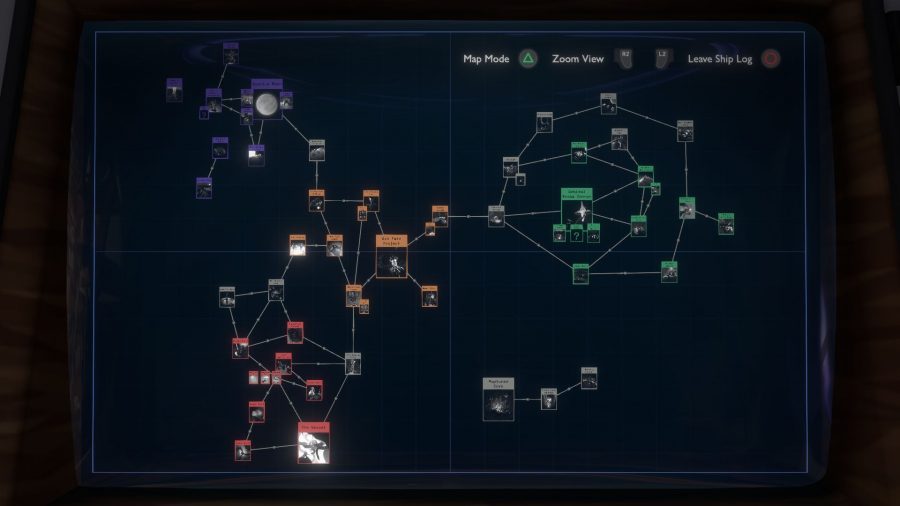

Outer Wilds is similar in that it includes a flow chart of mysteries to solve, but it’s even more important in this game because its structure is entirely open. It’s unclear what you’re supposed to do in the small galaxy you’re sent to explore, so you just poke around whichever places you feel like learning more about. With a game that’s this open and opaque, having a visualisation showing your progress and the knowledge you’ve gained along the way is an absolute necessity.

A big reason we’re seeing more and more games revolving around interactive mysteries is that it increases the potential size of a space without physically increasing the surface area of a game universe. Outer Wilds takes place in a galaxy that measures less than 50 kilometers wide in-universe. If the goal of the game were simply to cross it, you could travel from one edge to the other in just a few minutes. But every mystery in that small space will have you darting between planets and back again as you learn more and more about the nature and past of the galaxy.

Disco Elysium is even smaller, taking place on the equivalent of two small city blocks. But as you investigate different leads and peel back the layers of the characters of the Martinaise, new facets of the game world reveal themselves without actually changing its physical features. Full motion videogame Telling Lies has them all beat in the minimalism race, though, as the entire game takes place on a computer screen. The only interactive element that matters to the core story is the search bar, which pulls up video clips based on keywords you type in. Again, you’re trapped on a single screen, but the videos you find broaden the borders of the game beyond the edges of the monitor.

Speaking of search bars, it’s perhaps surprising that in the age of internet wikis that mystery games are thriving. But it’s for that very reason that audiences are more receptive than ever to investigating. Developers are harnessing our heightened sense of curiosity through web surfing, turning its addictive breadcrumb trail of discovery into videogames. The entire premise of Telling Lies is to root out the secrets of its main cast by searching for videos, which is what you’d be doing anyway if you were to look something up on a wiki or on YouTube.

By ‘gamifying’ the act of research, videogames have made mysteries even more enticing to pursue. In the case of Telling Lies, it’s the entire driving force behind playing the game; once you’ve uncovered enough information, you can trigger the game’s ending whenever you see fit, or you can continue to chase leads until you’re satisfied. Mystery is elevated alongside games’ more traditional motivator, achievement, as the reason to keep playing.

People are naturally curious, so it’s no surprise that mystery games have taken off. But it’s thanks to refinements in design over years of gaming history that they became a major part of the industry zeitgeist in 2019. We want to follow leads at our own pace and be trusted to chase them in any order. We appreciate a visual aid that plainly shows our revelations, accomplishments, and next steps. And we love research as a gameplay conceit. Most of all, mysteries make worlds come to life, allowing small areas to be dense with discovery and creating a living, breathing universe that we’re invited to learn about and master.