Our Verdict

An utterly original RPG that sets new genre standards for exploration and conversation systems, and a brilliantly written tragicomedy about our inability to let go of the linchpins of our identity. Even when they hurt us.

In a shanty town of tarpaulin and corrugated steel, a drunk is telling me a story about how he slipped and fell on his arse. I pick the cocky conversational response: “I would’ve landed on my feet. I have feline reflexes.” Turns out this is a hidden skill check against my sense of Savoir Faire, which replies: “No, you don’t.” I just got burned by my own psyche.

The drunk continues with a peremptory “whatever”, and there’s no discernible gameplay impact. But I laugh out loud, despite being a little hurt on my character’s behalf. I feel like I understand him better, and that I sympathise with him more.

The drunk rambles on, and a story that began as a light hearted, relatable tale of alcohol-induced misfortune takes a tragic turn as the consequences escalate: he loses his comfy house, his glamorous girlfriend, his lucrative job. The drunk blames all his current misery on that one heavy night. Guilt stings at having been so blasé in my initial reply, but there’s just a touch of ambiguity about his story, an attitude of backward-looking self-pity, and a hint that he had options to explore – and perhaps still does – which make him not wholly sympathetic. This is what Disco Elysium is like.

You play a detective who wakes up after a night of obliterative drinking with a purged memory and a shattered psyche. As a player knowing nothing of Disco Elysium’s weird and imaginative world, you learn about its history, politics, and unique physics (ooh) alongside your character. You emerge with an apocalyptic hangover into the Martinaise district of the city of Revachol, where a dockworkers’ strike is only the most obvious of many simmering local disputes. You have to solve a complicated murder case while navigating them all, despite your condition.

The fragments of your mind try their best to help you along the way, offering an endearing cacophony of advice – sometimes unreliable, sometimes conflicting, always well-meaning. They are a cast of characters in their own right. Volition is the determined grown-up in the room, Electrochemistry a slice of id forever seeking altered states, while histrionic Drama addresses you as “sire” or “my liege”.

These fragments are also skills into which you can invest points so as to interact more successfully with the world. You might need to check against your Endurance to examine a rotting corpse without vomiting, or your Physical Instrument to beat up a racist security guard. If you hit certain skill thresholds, the appropriate voice will analyse someone’s statements – perhaps for factual accuracy, or a hidden agenda – hinting at the best way to steer the conversation.

So these checks combine with your own diligence and judgement – how thoroughly you search a room, how deftly you navigate an interrogation – in getting Revachol and its citizens to give up their secrets. Disco Elysium does a decent job of making such secrets available to all builds so no approach is materially better than another: multiple skills may apply to a given situation, and many problems can be resolved in multiple ways (pry open a rubbish compactor or convince the hostel manager to give you the key, for example).

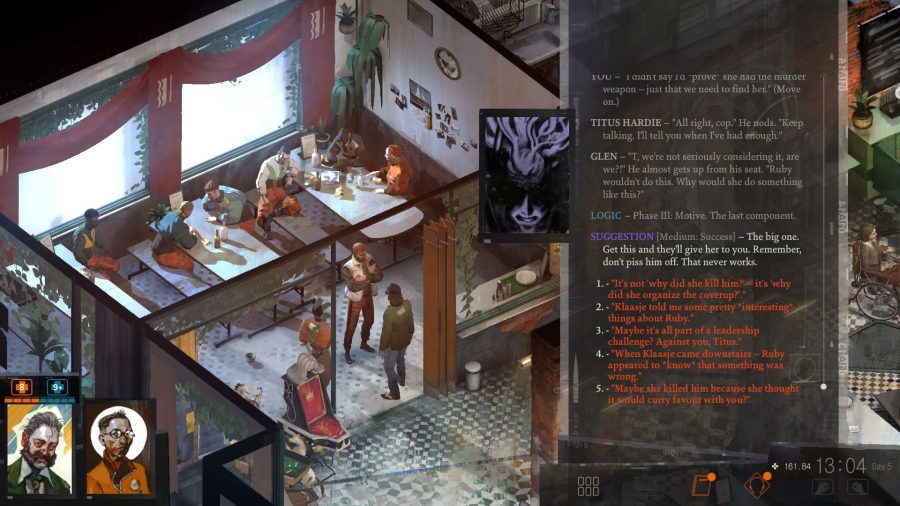

Your efforts are tested in several story-critical conversations with witnesses and suspects. It is magnificently satisfying to succeed in these inflection points because you did the groundwork. People will lie, deflect, and employ sophistry, charm, and ommission to make you doubt your case against them or their friends, and you may or may not be able to shoot them down with logic, evidence, and rhetorical tactics of your own. You need to not only ask the right questions, but resist the common RPG temptation of asking every question you can, in order to keep a witness compliant.

This is an RPG without combat, but which takes exploration and conversation to genre-pushing new heights. As you might imagine, you spend a lot of time navigating dialogue trees as they unspool on a backdrop of cassette tape, so the writing has to do a lot of work.

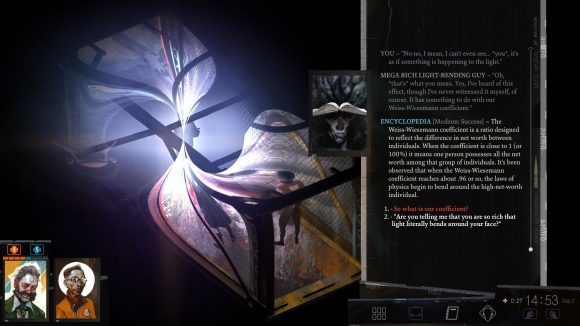

Fortunately, it’s consistently superlative. It is among the very, very best writing I’ve ever seen in games. Your shattered psyche and total ignorance of absolutely everything, even the axioms of reality, is a unique premise of which Estonian indie ZA/UM takes full advantage: no one’s told your sense of Rhetoric that you can’t persuade a shipping container to open its doors, or your Savoir Faire that you can’t teleport up a ladder.

On a less abstract level, you can exhibit a range of personality traits – or ‘copotypes’ – and take a range of political positions. Judge Dredd fans can go around saying “I am the law”, while apologising for your character’s many, many screw-ups can get you branded a ‘sorry cop’. You are invited to opine on political and cultural issues, beginning with the dockworkers’ strike in the very earliest dialogues.

Whichever position you take – even if you take none, which you can – ZA/UM isn’t content to let it sit comfortably. There’s sometimes a touch of South Park in the way that every perspective is criticised and ridiculed. When advocating the moralist centre to a eurotrance DJ who recalls Scooter’s HP Baxxter, I’m gratified that the impressionable dude adopts my position until he characterises it in these terms: “I’m swiftly moving toward a solution which pleases nobody!” Ouch.

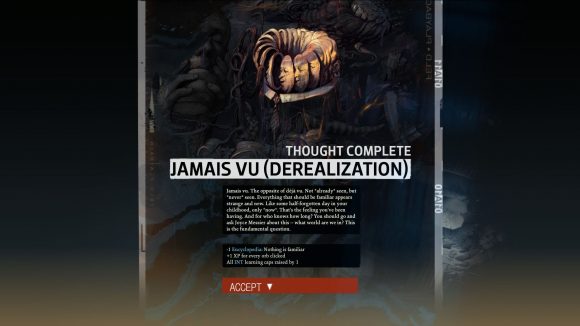

These personal and political traits add wonderful flavour to dialogues, but they also have a gameplay impact in that they can unlock ‘Thoughts’ (as can many other interactions). You can equip Thoughts to boost your skills and gain a range of other bonuses, as well as maluses. Defend ultraliberal economics often enough and you’ll get the chance to consider Indirect Modes of Taxation, which will cause further ultraliberal dialogue choices to generate money, but cost you a point of your Empathy skill to equip. Again, every position gets ridiculed.

Disco Elysium tries and succeeds in striking a number of different moods. One of those moods is humour, which got in the way of my role-playing a bit, because it’s so hard not to pick the funny option. In my first playthrough I put points into intellect and psyche skills, intent on role-playing a quick-witted rhetoritician. That all goes to piss when I’m able to request a handout from a rich lady by simply screaming “MONEY!!!” at her in capital letters. I won’t spoil the rest of the conversation, but I can’t remember the last time a game made me laugh so hard.

But Disco Elysium is so much more than just funny. It is angry. A missing person’s case in an impoverished fishing village concludes with some of the game’s iciest social commentary and its deepest humanity – yes, every position is criticised, but one senses that ZA/UM is more animated by some than others. If not that, then at least I was more animated by certain criticisms than others. Either way, it’s welcome. There needs to be room in this medium for games that are willing to provoke.

Disco Elysium is also bittersweet. My alcoholic amnesia has erased the feeling of missing someone, so I ask a chilled yet melancholic truck driver about his family after bonding with him over poetry. He says it feels: “Good. And bad. An ache that brings you joy. I think of them a lot. I dream up these silly scenarios, in great detail. Of living with them. It comforts me.”

I once thought that isometric RPGs struggle to evoke a sense of atmosphere compared with games that take a more immersive first- or third-person perspective, but Disco Elysium has done it. Haunting, crystalline music (by indie rock band British Sea Power) and carefully deployed ambient sounds, like lapping waves and rustling reeds, brilliantly support your sensory voices when they invite you to stop and drink in a scene, as they often will. Perception tells you what you hear in different directions, while Shivers can attune to the thrum of the city, flying across its frigid bay to bring you stories of its people. Revachol isn’t a traditionally pretty place – it’s all boarded-up businesses, broken masonry, and reinforced concrete – but it has more character and authenticity than most gaming locales. I love it, because I feel like I know it.

My first (fairly completionist) playthrough – that of the intellectual centrist who imagines himself a rock star – took me a solid 35 hours. I’ve started a second, focusing on physical and motorics skills and championing ultraliberalism. A few key conversations and interactions have gone more differently than I had expected, and while the major story beats haven’t changed, my knowledge of what happens is actually keeping me engaged because I know how to do things better or differently. Enough has changed for me to happily finish a second run.

Criticisms? I guess I have a few. Some signposting in the late-game is lacking – there are quests you’ll think you can advance, but which are actually dependent on something else. Disco Elysium doesn’t welcome min-maxers, either; you can’t see what a Thought will do until you’ve fully ‘internalised’ it, and if you don’t like its effects, you have to spend a skill point unequipping it. Expect to fail many skill checks. Annoying as this may be for those who like to ‘win’, this is one of those RPGs where role-playing and storytelling is the goal. The odd malus and the odd failure makes things more interesting. ‘Winning’ isn’t really the point, but you can always reload saves to retry failed skill checks if you want.

And these are trivial imperfections in a shining gem of a game. There’s so much more I want to say about Disco Elysium, but a lot of it risks spoilers, and hey, you get it by now: This is one of the best games of the year. Please play it.