Mass Effect 3’s Codex has 210 entries: 40 ‘primary’, 170 ‘secondary’. They provide a comprehensive history of all of the galaxy’s races, living and dead; their planets, their ships and their weapons; their biology and last breakfasts. It doesn’t end there, though – there’s even a ‘personal history summary’ for the emotionally inattentive. Depending on which origin story you picked for yourself in character creation, you’ll be informed either of how “eager” you were to find a better life than that on Earth, or how “all you loved was destroyed” on your colony home planet.

Practically all of these 210 entries will pop up in clusters over the course of an average playthrough. And when they do, each player will have to make a decision. Do I eat my story peas now before I dig into the steak, and get them out of the way? Or face the prospect of 100 or so unread entries later? If the latter, do I catch up on the Codex during my commute with the Mass Effect 3 datapad app, as an alternative to the Financial times?

It’s clear how this particular practice came to be, popularised by Mass Effect and copied in every second RPG since. If your aim is to aggressively streamline the genre as an action-heavy take on the choose-your-own-adventure story, the interactive in-game book becomes an unhelpful mid-sentence full stop to your carefully-controlled pacing.

For years, RPGs have stored found notes and diaries in menu-based journals for reference; BioWare merely took another step forward and removed them from the game world entirely. Simply interact with a tome to have its entry added to your ‘lore’ section. And so the biographies have grown more comprehensive, and the worlds they describe fuller, yet somehow smaller, as their shadows and ambiguities have been expunged.

It took the arrival of Dishonored to shake us by the shoulders about a great many things and say, “You don’t have to do it that way”. Chief among those is its approach to lore, which it doesn’t really do.

I’d be hard-pressed to tell you about Dunwall’s relationship with its neighbour states, or even the name of the world it inhabits. Instead, the detail is saved for the peripheral stuff. The process by which whales are hauled onto great boats and then stripped of their flesh as they’re transported still-living back to port, for instance, is afforded all the grim focus of a Wikipedia article. I’ve read Whaler’s Songs in discarded children’s books, and seen those same boats crop up time and again in paintings. I’ve been given time to ponder the implications of a world whose Da Vinci, Anton Sokolov, designs such things.

In Dishonored, if you want to know about the rich and the poor or what lies beyond the river – the sociological and geographical stuff that BioWare simply gives away in their codexes – you’ll need to parse it in poems and academic papers; via offhand comments and overheard conversations.

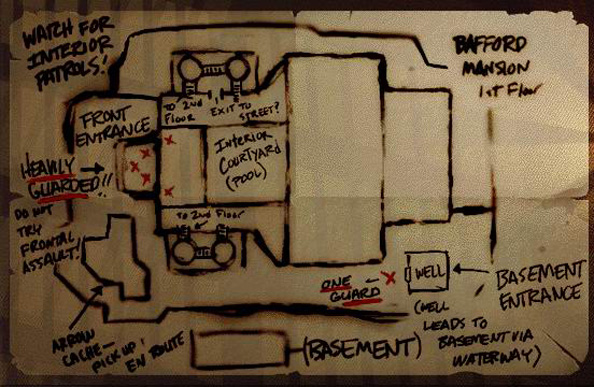

It’s an approach ripped straight from Thief, the seminal Looking Glass stealth game. Looking Glass had an approach to information dissemination akin to the KGB, and the Thief series always painted its world in broad strokes, to say the least. Here’s an in-game map, from early mission Lord Bafford’s Manor:

Assembled from whatever information protagonist Garrett could glean before heading out into the night, Thief’s maps were rough navigational guides at best – made ambiguous by frequent question marks, inaccuracies in scale, and reams of white space. Once you got there you might find an entirely different space – or indeed, never find some of it at all.

The same was true of the game’s wider world, the nameless City. The City and its abstractly-named districts – ‘New Quarter’, ‘Old Quarter’, ‘Docks’ – would expand and shrink over the course of the series according to the needs of its designers, and was all the more mysterious and compelling for it. Though it bore a very specific industrial character, its limits were never defined, and its white space never filled in.

Mass Effect has an issue, and I think it’s at least partially one of formatting. Dishonored treats its snippets of story like rewards, secreting them away in odd corners to be discovered alongside runes or bone charms. Conversely, BioWare files its lore away like chapters in a textbook, as if it might be a chore to read – and lo, what do you think it becomes?

Yes: an issue of formatting, more than anything. But that formatting is indicative of a wider, stranger thinking, in which the merits of games writing seem to be measured in volume. Not wit, thematic integrity, or tears, but sheer weight in words. Put the RPG on the scales and we’ll see whether it’s finished.

Look closer and you’ll see it’s been happening for years. It’s there in BioWare’s curious boast that The Old Republic hosts 250,000 to 280,000 words of dialogue – about five Infinite Jests. It’s there in Peter Jackson’s approach to The Hobbit, which sees a modest there-and-back-again expanded to global scale, fully backstoried and botoxed with ominous hints at an irrelevant supervillain’s return.

I really like Mass Effect. I’m especially partial to Dragon Age: Origins, which is just as guilty of codexing its world. These are good games. That’s why it’s a shame that all of this world-building, all of this lovingly assembled backstory, is so ill-served by its format. The fact is that RPGs are sold with the promise of two things: choice, and lore. That’s not likely to change. But the latter needn’t be TL;DR’d in large blocks of offscreen text. Our worlds deserve better.