The reason I’m writing about a board game for a PC gaming site, and the reason I quickly feel comfortable playing it, are one and the same: it’s a lot like Divinity: Original Sin 2.

After a brief jaunt from PCGN house, myself and Carrie sit down at a table in a hotel basement, along with a few other pleasant folk from the local game press and Kieron Kelly, producer at Larian Studios. A character board lies before us full of familiar icons in an unfamiliar context – I am a Rogue, and recognise that I am skilled in being a Scoundrel – and I have a deck of cards to represent my abilities.

While the board game’s mechanics are new, knowing what something does in the videogame makes the process of learning more like being gently lowered into them, rather than tossed into the deep end.

When it comes to combat, for instance, I understand that Throwing Knife will be one of my very few ranged skills, and that Cloak and Dagger should enable me to turn invisible. These expectations are all accurate. I also get a special ability called ‘The Pawn’ which lets me make a free move, and I get +2 to my initiative, meaning I’m generally first to act.

It’s weird to be looking at a tablecloth and a scattering of colourful cards and yet have flashbacks to my playthrough of a videogame, when every fight would start with Sebille and her enormous movement range, but that’s kinda how it feels.

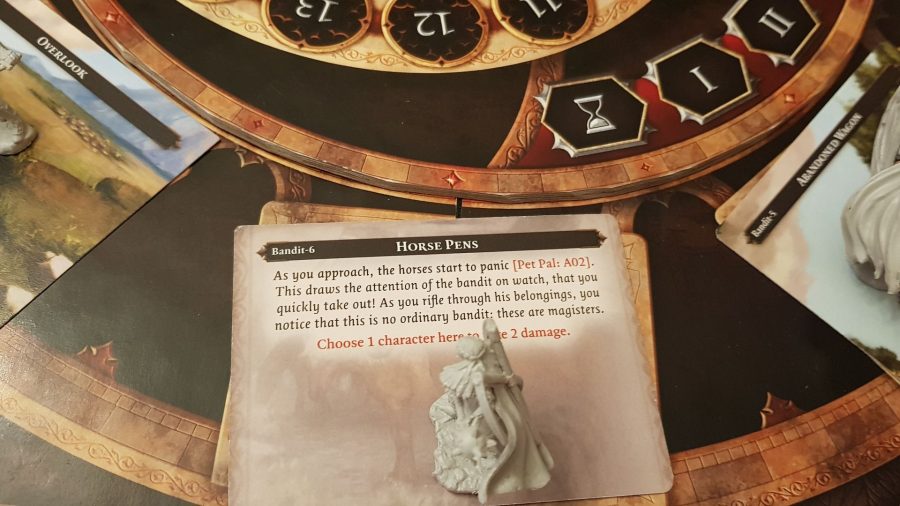

I’m getting ahead of myself, however – more on combat later. The Divinity: Original Sin board game flows around ‘encounters’, which are built of eight location cards slotted into the roundel at the centre of the table. Exploration is abstract: we discuss who should go where and simply put our figurines down on the location cards, which are then flipped to reveal text describing what happens. You might discover some loot, some information hinting about future encounters, spawn some enemies, that sort of thing. When everyone in the party has resolved their location card, that’s one turn.

We complete two encounters, each limited to three turns, in about three hours. Allowing for a snack break and the fact that we’re learning, confident players could probably complete either of them in an hour, so I reckon an average turn may take roughly 20 minutes. The turn timer goes all the way up to eight, suggesting there will be much larger encounters than these, but it’ll be cool to have this way of estimating how much time you’ll need when budgeting your evening’s commitments with your gaming group.

The turn limit also creates some nice tension. With a party of four we have to split up if we want to explore every location before time runs out, but we also know combat is coming and that when it does, moving between locations will cost action points. We’re obliged to have a bit of a chat about who should go where and how closely we need to stick together.

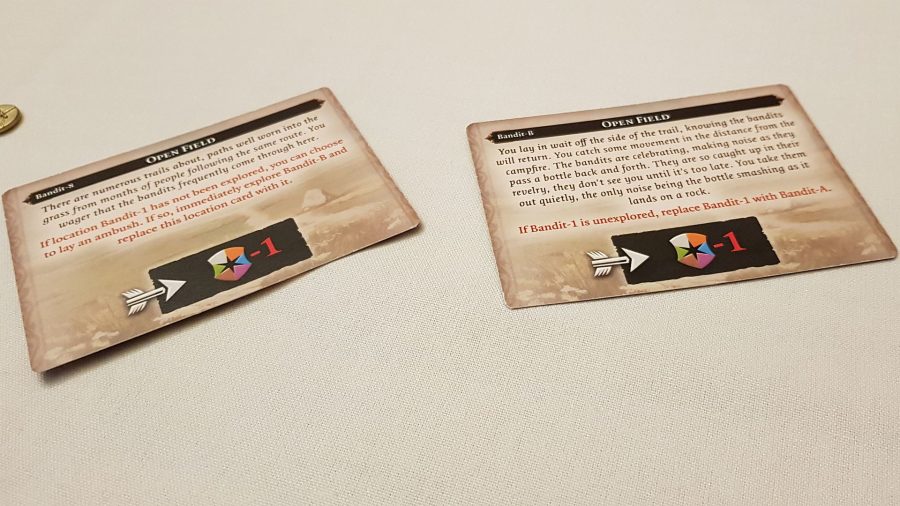

This is further complicated by the modifiers on each location card, all conveyed via a clear, icon-based visual language that reminds me of Terra Mystica (which can somehow depict its immensely deep mechanics without using words at all). A -2 flame and a +2 water droplet on a Campfire location, for instance, clues us in that any enemies who spawn here will have their resistance to fire damage reduced and their water resistance increased – a bad place for our Hydrosophist mage, then.

Encounters can vary per playthrough, depending on how things have gone previously. There may be two different versions of a castle’s location card – one where it’s intact, another where it’s been burned down – and if the party has screwed up, the card that’s used is the smouldering ruin. A storybook directs Kieron to set up each encounter accordingly, much like a choose-your-own-adventure novel (any player who knows the game can do this, however – a dedicated GM isn’t necessary).

This also enables a tabletop equivalent for another of the videogame’s bright ideas – the tag system. Say you’re exploring a stable. You flip the location card, which offers the default outcome as usual – but if your character has the much-loved Pet Pal skill, which lets you talk to animals, the storybook overrides the default text with a new entry in which you have a nice chat with the horses. Other tags are associated with your character – as Ifan Ben-Mezd, I am both a Soldier and a Scoundrel.

Again, location cards offer a neat bit of visual signposting to inform your exploration – we send our Pet Pal mage to a particular patch of forest because there’s a squirrel on the artwork. The loudest cheer of the game comes when the card is flipped and the text does indeed mention a squirrel and a Pet Pal tag.

Thanks in part to animal advice and my rogue’s affinity for innocuous-seeming fields, the first encounter goes “about as cleanly as it could’ve”, Kieron says, with a touch of disappointment. We set an ambush in one of those fields, which removes a couple of enemies from the final location card (a suspicious campfire), and discover a magister ranger in the second, who we pick off before tackling his mates.

It could’ve gone very differently. Kieron recalls another session in which, by exploring the camp first, the party had to deal with a harder encounter there at the same time as several rangers who bombarded them from a distance. It was very cool to see the game has this capacity to reward considered exploration, but some encounters do also seem to have an element of blind luck to them – in our second encounter were three totally identical forest locations that, unless we missed something, gave nothing away. One concealed a boss.

I’m comfortable with this. Randomness has governed enemy spawns and plenty else in tabletop and videogames for ages and the sudden appearance of an overwhelming foe, even if arbitrary, is a party-bonding moment that’s especially potent when it occurs in person.

Perhaps the most videogame flashbacks occur when combat does kick off. You’d think the ability to coat an area in water or oil and then modify that surface with an element, an interplay that defined combat in the videogame, would transfer well to a grid-based board game, but all the action remains on the roundel and its location cards. Melee attacks require you to share a location with your target, while ranged ones can hit enemies from a card or two away. As for that interplay, area-of-effect spells like Rain affect every character in each location, and can confer status effects that modify other attacks.

The two-day UK media tour for @larianstudios #DivinityOriginalSin board game begins! pic.twitter.com/lEEZHgGU1n

— Dead Good Media ➥ ☀️ Summer Game Fest (@DeadGoodMedia) December 3, 2019

I trust the potential for Divinity’s classic friendly fire is already clear. After it’s judged necessary that our Wizard should hit the aforementioned boss (a Ghoul) with a Fireball because it’s resistant to everything else, and I happen to be sharing its location because my only ranged attack is on cooldown (calculated in turns), I am lit up just as Sebille always seemed to be in the videogame. Kieron tosses me a token for my character sheet describing the downsides of being on fire (2 damage every turn, -2 fire resistance, +2 water resistance).

This quandary is helpfully resolved by our other mage – the Hydrosophist. He can’t cast Rain, because that would douse the Ghoul, so instead he intentionally shoots me with his water wand. What guarantee do we have that he won’t kill me? Blind faith that he’ll screw up the damage roll.

It’s a risk, but a calculated one: the attack will use blue dice, which deal lower average damage but have a higher chance of triggering a weapon or ability’s special effect, if it has one. Good for mages who want to set things on fire, bad for DPS characters like me, which is why most of my abilities use the default black dice. There’s also a red set of dice which deal huge damage, but are rarely accessible.

It’s all pretty great. A little experience with the videogame definitely helps – not only to pick up the rules, but also to enjoy these lovely little moments when different systems in a different medium recall the splendid idiosyncrasies of one of the best RPGs of recent years.

Larian and board game developer Lynnvander Studios still have to polish their prototype – both of a couple of imbalanced abilities, and because someone spilled coke all over ours. But in all but these most granular details, Divinity: Original Sin – which is due to release in October next year, according to the Kickstarter page – plays brilliantly, and eerily like the videogame we know and love. If you’re in need of a list of the best board games, our sister site Wargamer has you covered.