Baikonur, one of Kazakhstan’s most well-known cities, houses the only existing launch base for flight missions to the International Space Station. Three astronauts arrive and are packed onto Russia’s Soyuz capsule, hunched over like meaty cargo, and fired into the stratosphere for the six-hour journey. Now other countries want to regain a foothold on the stars – in August 2018, Boeing’s Starliner capsule will take an unmanned mission to dock with the station. If this automated test is successful, a manned flight is planned to go ahead in November 2018. Strangely, videogames will have a fingerprint on these advancements.

Explore beyond our planet with our list of the best space games.

Right now, one Australia-based VR development studio is helping Boeing fulfil their spacefaring dreams. But that collaboration is not the only unlikely story in this commercial space race. You see, the company working with Boeing, Opaque Space, is headed up by a former nightclub bouncer turned game developer, Emre Deniz.

“I’ve only been in the industry for about three or four years, so the only games I’ve managed to work on so far are a couple of small indies,” Deniz tells me. “Prior to that, I worked at something called Virtual Dementia Experience, which won the Microsoft Imagine Cup World Citizenship Award last year. I’ve basically been working with serious games the entire time.”

People are always looking to legitimise games as art, but we often overlook their real-world applications. Away from traditional experiences, they are helping push the boundaries of human advancement, simulating illnesses such as dementia, and creating training modules for medicine, military, and even aviation.

The people at Opaque Space are not astronautical experts – they are game developers. The closest any of the team have got to the stars prior to their current projects is developing Visceral’s survival horror series Dead Space. They have developers who have worked on indie games, people who helped develop Battlefield and Need for Speed, and others who have made VR titles. None of them ever considered that they would influence the human spaceflight programme.

“We had pretty ambitious hopes in 2016, just like every other VR developer, and we thought that the VR market was going to fly off the handle and everyone was going to go out and buy kit,” Deniz remembers. “But that wasn’t the case. So, as we were working on it, we really started seeing the numbers correct themselves and the market find its actual point. That correction led us to think about what more can we do, or what can we do differently.”

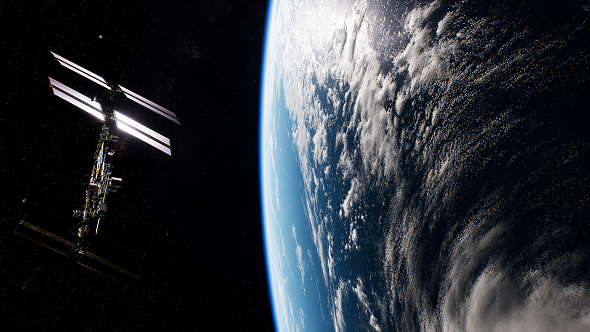

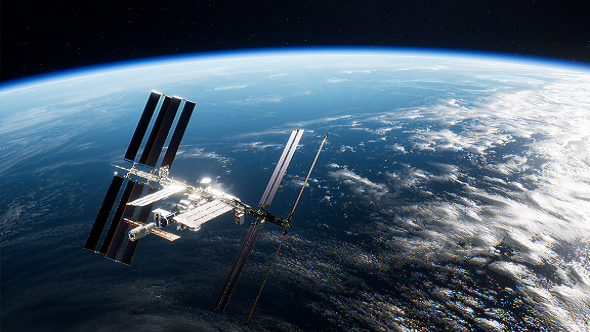

Opaque Space were making a VR game called Earthlight at the time, in which you take part in a space walk on the ISS, hanging above our planet as weather patterns form on its surface, clouds swirl, and the big blue orb slowly rotates below. To make the game as authentic as possible, the team collaborated with NASA during development, asking for reference photos and digging into the logistics of space missions. NASA soon began to realise, however, that the collaboration could work both ways. It was not long before Opaque Space were at the Johnson Space Center performing an integration test on ARGOS – NASA’s Active Response Gravity Offload System – a training method used to acclimatise astronauts with working in zero-gravity conditions.

“We were having lunch and an engineer from NASA turned around and said, ‘Hey, maybe we can get you guys to come over to Johnson Space Center and see if your content works on ARGOS’,” Deniz says. “Prior to that, we had passed over a model of the Earth which was being used actively in the research and tests that they were doing on different training methods, so we already had a good relationship. But they kind of just dropped the mic on us and said ‘Would you like to start discussing some further collaborations?’”

Now, Opaque Space are working with NASA to plan for future missions, preparing astronauts in VR and mixed-reality for inter-vehicular (IVA) and extra-vehicular (EVA) activity in low-Earth orbit. On top of preparing astronauts, these VR simulations can act as refresher courses for veterans and even provide biometric data for NASA to analyse. The end-goal of all this? To contribute to the NextSTEP programme – humanity’s new giant leap for mankind.

“These include surface operations on Mars, as well as surface operations on the Moon,” Deniz explains. “We’re looking at things like orbital habitats, surface habitation, surface activity – it’s building itself up to become this thing where we can take someone into the Soyuz capsule and have them perform a flight mission to get onto the ISS, then dock with the Starliner if that’s the case, then jump onto an EVA on the ISS, step onto the surface of the Moon, and then, hopefully, also look at habitation and human presence on Mars as well, which is a program we’re quite interested in right now.”

While Mars is certainly on the agenda, Opaque Space prioritised working with a virtual recreation of the Moon. As SpaceX’s Elon Musk once suggested, a forward operating base on or orbiting the Moon would be a gateway to future missions further into space. “My philosophy at the time was ‘no-one is going to Mars until we get to the Moon’ – the Deep Space Gateway is a great example of this,” Deniz says. “Lockheed is planning on putting a habitation on the Moon, and they’ve shown different concepts and prototypes. Some of those prototypes have been shown in VR for the first time. Boeing and other companies like SpaceX are interested in the NextSTEP program. Everyone’s looking to get to the Moon first, then Mars.”

The team at Opaque Space might be made up entirely of game developers, but they are now an integral part of humanity’s galactic journey. They even have official mission badges. “It’s a project that’s bigger than us, in the sense that we come into work every day and I see people working on things, and a part of my brain is like, ‘Do you understand that these people are working on content or assets or things that enable people to get to space?’,” Deniz laughs. “It’s crazy, right? It doesn’t make any sense – why would a bunch of game developers operating out of a studio in Melbourne have a fingerprint on the human spaceflight program? It’s this really weird concept. I’ve gotten better with it.”

Opaque Space are so integrated into the projects now that they have a Slack channel with NASA engineers. Deniz has even been to Mission Control and spoken to the pilot operating the ISS in a livestream. A surreal experience for anyone, but it is an even more unexpected journey for a one-time nightclub security guard, now head of a games development studio specialising in VR.

“There is a degree of professional humility that we exercise,” Deniz admits. “We engage and speak with a lot of academics, we talk very candidly with engineers at NASA, asking them the things we don’t understand or don’t know. We are also engaged in a lot of research. We have conducted around two years of study into the field of IVA and EVA operations, surface operations – we’ve gone as far as sticking my head in the astronaut helmet to see what the visibility is like, put Gopro cameras over the surface of suits to look at the surface texture, studied the composition of those materials, talked with everybody from the astronaut candidate program to the flight director of the ISS whilst he was flying the ISS about the different nuances of their work.

“It’s a balance of gathering references, having a very detailed look the things that we’re depicting, to asking the experts every single day. It’s given us an appreciation for the vastness of the field of aerospace.”