The indie renaissance which has swept across the PC gaming spectrum over the last few years has brought with it scores of side-scrolling, two-dimensional, retro-inspired platformers. Loved by many for their nuanced yet ever-so-subtle tweaks that bring each game’s mechanics in-line with contemporary expectation – not to mention their insatiable tinges of nostalgia – these games serve to celebrate not only the classics of yesteryear, but also the ever-widening scope of what defines a ‘modern’ videogame in present day context.

Given the multitude of 2D sidescrollers that fill the PC market nowadays, it’s easy to forget that consoles were once the platform of choice for these games, in the ’90s, when the genre reigned supreme. Sure, these games might’ve landed on the Mega Drive or the SNES first, but the upshot for PC owners was that they then got the definitive versions; the most polished and, ultimately, best all-round experiences. Earthworm Jim was one such game.

Nowadays, ex-Acclaim Games CCO and current Gaikai founder and CEO David Perry lives in Orange County, California – a far cry from the rolling hills of County Antrim, Northern Ireland where he grew up. While still at school in 1982, he programmed his first videogame aged just 15 on his home computer – a Sinclair ZX81. Two years later, not long after his 17th birthday, he moved to London where he worked for a string of developers making games for the ZX Spectrum.

Perry eventually landed a job with Virgin Interactive, which by 1991 saw him transferred to Virgin Games USA, the company’s United States division, leading development on the likes of Cool Spot, Aladdin and The Jungle Book. In 1993, he left to set up his own venture: Shiny Entertainment.

“It was a real growing up moment,” says Perry of starting out on his lonesome. “It made me realise that you really can do just about anything, as long as you start. I knew almost nothing outside of programming and yet by just making things happen you learn in real-time. I still do this today and is probably the best advice I can give. You can learn and do just about anything in the game industry, but you have to start by diving in from the high board.”

Shiny’s first game, Earthworm Jim, would be an ambitious project. Following the success of a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles licensing deal, US toy giant Playmates Toys wanted another hit, and so approached the developer with the idea of kicking off a new franchise.

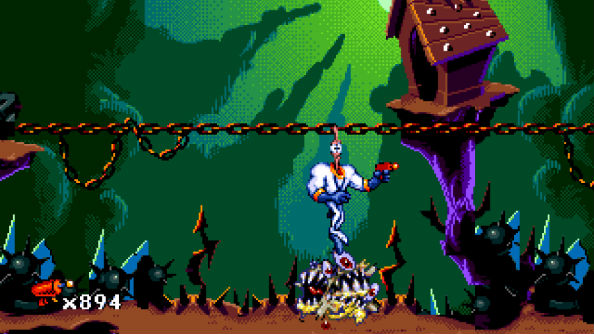

Not only was this an unusual approach for the time – the anthropomorphic Turtles had found success in the realms of comic books and TV before moving over to games – but Earthworm Jim would also enter into the already heaving 2D platformer spectrum with a less than orthodox protagonist: a defenseless earthworm personified by virtue of a superhuman suit who carried a ray gun and also used himself to whip foes and grapple the capricious terrain offered up by each level. It was a bit out there, to say the least.

What the team had in mind, recalls Perry, was to create something that was humorous but not necessarily strange. They would throw ideas into a hat, see if each made other members laugh, and if it did they’d make it stick. Popular TV shows at the time – such as Ren & Stimpy and Beavis and Butt-Head – rode the line between strange and funny with prestige, thus Perry et al focused on recreating this idea in their videogame.

“It’s true, we did resist the urge to make conventional design documents,” says Perry. “We had a simple way to develop based on what we thought felt good, meaning we’d play around with ideas and when something felt good it became a level. I think it made the whole thing much more fun to work on, and much less predictable. It was tough to tell what would show up next and we liked that.

“The platform genre was flooded with games; some were really, really good, so we were buried in scary-good competition. Earthworm Jim still managed to get a lot of magazine covers, awards and licenses including a TV show, and looking back I think it had a lot to do with humour.

“[Humour] is the one thing missing in a lot of competition. The best platformers commonly had great graphics, music, design, but no humour. So maybe that was the DNA of a way to get attention in a sea of competition. I still feel that way today, there are far too many serious games. If I had to compete, I’d pivot to humour.”

Although having cut his teeth on PC games, Perry was now focused on delivering Earthworm Jim primarily to the Mega Drive and Super Nintendo respectively, yet a PC conversion was always something Shiny had in mind. Unlike most studios at the time, Shiny did all of the game’s animations with paper and pencil primarily, before translating the hard copies via ‘animotion’ – a process whereby paper animations are converted into digital data.

Against the technical limitations of the target 16-bit consoles, the team’s programmers relied upon smoke and mirror techniques to deliver visuals as clean and as close as technically possible to the 2.5D aesthetics the designers demanded. By splitting the play area into strips from top to bottom and allowing the strips to scroll from side-to-side separately – such as in the movement of clouds – levels could capture the illusion of depth and were thus more encompassing. By the time Earthworm Jim made the switch to PC in 1995 courtesy of publisher Activision, this process was finely tuned, polished, and looked well ahead of its time.

One of the most striking aspects of Earthworm Jim’s humour is the renowned launching cow scene at the very beginning of the game, where you have the choice to drop a fridge suspended in mid-air onto a platform that catapults a cow upwards and out of sight. “Cow Launched” heads the screen, before you carry on as normal.

“People thought I was obsessed with cows, for some reason,” says Perry. “I can’t remember why it started but every gift I got at the time would be a cow gift. I ended up with an entire room of cow stuff in my house until I accidentally said I prefer giraffes – probably because I’m insanely tall. Then I got swamped with giraffe stuff. So now I like Ducati motorcycles, but nobody has been buying me those. The cow, though, that is a great example of Doug in action.”

Animator Doug TenNapel (who worked on the early ’90s cartoon Attack of the Killer Tomatoes) first met Perry during his own interview at Virgin Interactive in mid-1993, a few weeks prior to Perry’s exit. After a few of Virgin’s staff followed suit to join Shiny, TenNapel expressed his desire to work with Perry and that if “an opening ever came up” he’d love to be considered. About a month after this conversation took place, a vacancy at Shiny did present itself. TenNapel pitched Earthworm Jim – a character he’d been working on privately – and was offered a role.

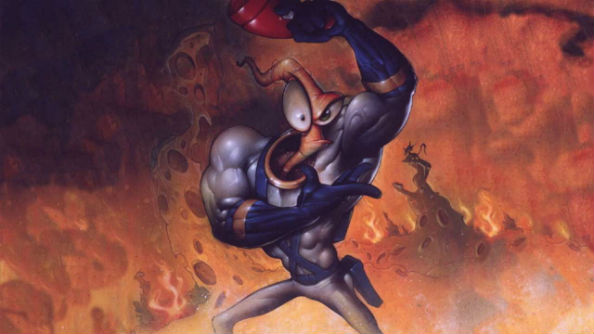

“Earthworm Jim was a pretty common kind of thing I was creating back then,” says TenNapel. “It had to be simple due to technical limitations at the time, so the character’s initial design, name and clear qualities needed to be perceived at first glance. There wasn’t much room for subtlety, so the limitations helped me with exaggeration.

“I knew I wanted a human frame for Jim, because as an animator it’s a greater challenge to animate something so familiar as human anatomy. I was inspired by Warner Bros. characters like Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck and Tasmanian Devil, they too have a familiar form that looks closer to humans than the animals they represent.”

After creating Jim, the rest of the crazy cast followed suit. ‘Professor Monkey-for-head’, ‘Princess Whatshername’, ‘Queen Slug-for-a-Butt’ and ‘Psycrow’ all marked TenNapel’s daft sense of humour as he became what Perry best described as an “ideas and animation factory, fueled by Johnny Cash music and Tex Avery laserdiscs running 24/7”.

Within Shiny, TenNapel’s outlandish vision was allowed to thrive uninhibited and unrestricted – something TenNapel himself puts down to the inclination indies harbour towards risk. To TenNapel, indies are in a position where they have to take risks and that doing otherwise defeats the purpose of being independent in the first place.

“At Shiny, we could pretty much do anything we wanted,” he says. “I don’t recall Dave or my fellow team-mates ever telling me ‘no’. At most of the other companies I was at all I ever heard was ‘no’. And that’s their loss.

“At a different company, or even at Virgin Interactive, there would likely have been reluctance, but that’s why the timing of everything all the way up to the publisher fell into place so well. It was a perfect storm. As we made Earthworm Jim, it didn’t seem alien to us at all. We were charmed by the character, and we were excited to see our audience respond to it. We were pretty confident that what we made was working.”

And work it did. To TenNapel, Shiny was a team operating in unison, that had a perfect sense of would flop and what was worth exploiting, and that individually rose above what they were capable of. A “young energy” is what he suggests “fanned the flames into a frothy, creative, workaholic team” that was capable of delivering a successful game and equally as successful franchise as per Playmates Toys requirements.

Earthworm Jim launched to much fanfare and success on consoles in 1994, and was packaged alongside its equally well received sequel when the PC iteration arrived the following year. Both games have since been released on almost all platforms – Interplay brought the original to Steam in 2009 – with several spinoffs reaching mobile devices and handhelds.

A television series ran between 1995 and 1996, and there was a comic book series shortly after. Playmates launched a line of action figures and celebrated the titular hero’s wave of celebrity status by plastering his face onto anything they possibly could – clothes, lunchboxes, pencil cases, school bags, to name just a few.

“The TV show was a big deal for us as it was probably the first TV license-out from an indie developer,” recalls Perry. “Marvel made comic books and that’s where we realised anything was possible. Playmates made toys and soon Earthworm Jim was getting major attention.”

At one stage during the hyperbole that was Jim Mania, a feature-length animated movie was on the cards. Perry and TenNapel don’t quite see eye-to-eye as to how this might’ve panned out, however.

“The mistake we made was giving Universal the movie rights without a requirement to fund the movie,” says Perry. “Sony approached us to make the movie and Universal declined. I wish that movie had happened.”

“I’m on and off about the movie,” interjects TenNapel. “I’ve written a treatment, and am pretty protective of the Jim universe. I have a hard time letting other people create in that space particularly when they go so far afield from what I think Earthworm Jim should be. But that said, I’d rather the fans have a movie, nearly any movie, over a movie that I demanded was perfect.”

Either way, Earthworm Jim the videogame was an undeniable classic. It was an injection of originality into a well-worn genre and its ability to deliver humour – crude and slapstick as it was – into a game, at a time where humour was almost nonexistent in the medium, is something to be commended.

The backing that Shiny received at the time, the wealth of expertise the team was pulling from, and the unadulterated creativity that galvanised their creative process likely pointed towards Earthworm Jim’s success prior to release… and TenNapel agrees, at least on a personal level.

“I can always see anything I make as super popular!” says TenNapel rather unashamedly. “That doesn’t always happen – in fact it hasn’t happened for any of my other projects the way it happened for Earthworm Jim – but I don’t put the time into something if I don’t think it can defy cultural gravity.”