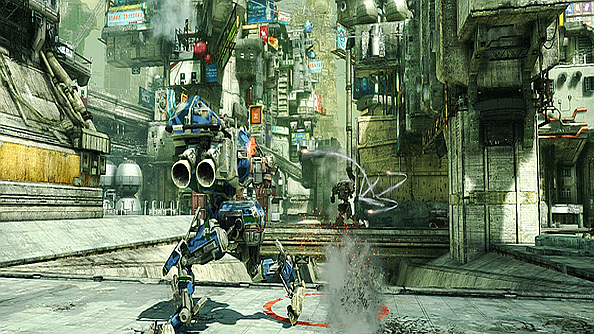

PC gaming: it never stops. Yesterday, Adhesive Games launched Hawken – a ridiculously impressive stompy robot shooter. It’s a gorgeous looking thing: a game that shows off what the PC is capable of when tech is placed in the hands of talented artists.

But it’s a bit more than that. As one of a growing number of free-to-play FPS games it’s a potential contender for next year’s most popular title. It’s fast, slick and hefty – but with a smart progression system that rewards extended play.

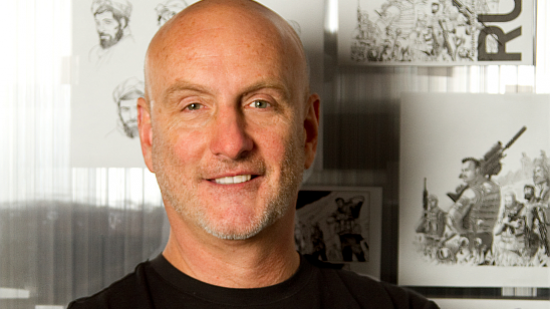

On the eve of it’s launch, I sat down to chat with Meteor Entertainment’s CEO Mark Long, to talk about the challenges ahead, and why just getting through the game’s first day would be a major achievement.

Tim: So… you’ve got a day to go before you flick the switch. How are you feeling? Nervous? Confident? Scared?

Mark: Pretty aggressively confident that the platform is going to perform. The big thing for me is that I didn’t want to be the one to fuck up one of these big global launches. There have been so many of these games – like Diablo, League of Legends, where I have been trying for weeks to get in to play a game. It would be nice to actually be able to get onto a server and play a game when everyone is trying to. It’s a pretty modest goal but, actually, one I haven’t seen pulled off yet.

Tim: I understand that you’re doing something quite complicated with your servers: using Amazon’s Web Services to power your back-end.

Mark: It is complicated, but another way of looking at it is that it’s the same technology that powers Netflix and Kindle. These are weapons grade server platforms. The theory is that it can scale infinitely. But we haven’t really seen the concurrency that we think we’re going to have to test the theory. Of course, we can run simulations. But it’s never the same as people doing fucked up things.

Tim: So, you’re expecting, say, an order of magnitude more people tomorrow playing?

Mark: Yeah, at least, yeah. It’s hard to predict how many people will want to play. We’re told that free-to-play launches go very slow. They say it’s a very long incline, and shallow. Not to expect big numbers on day one. But there’s such a high awareness of the game – and we’re coming out in the holiday season, after everyone has gotten their fill of Halo 4 and Black Ops, so I’m hoping they’ll give us a shot.

It might be a couple of weeks before we really ramp up. A lot of our data shows that the majority of players have registered so far, like 60%, have some college education and are in the age range of 15-25. So they’re probably in school. So it may be that our launch day won’t necessarily be a big day. Friday will be the big day, when everyone comes home after school.

Tim: So you better pray that they take their PCs home for Christmas.

Mark: Yeah, exactly.

Tim: Did you ever consider making Hawken not free-to-play?

Mark: Absolutely not. That’s going backwards. You’d have to be an idiot to look at the data and the market and not see that free to play is the way to go.

We’re coming in between console cycles and traditionally we’re seeing PC gaming spike in between cycles – that’s because we see that PC gaming graphics surpass consoles that are getting long in the tooth. You also have markets emerging that were never there before, like Russia, Brazil, Turkey, China.

The other thing: I don’t know about you but I used to play everything. Now I only play a couple of things, but I play a ton, like 10 times more, on tablets.

Ultimately I think that tablet is going to be the defining platform. But we’ve got a ways to go. You basically need to have super-tablets that can console level graphics, wireless HDMI and a good bluetooth controller that’s ubiquitous. But all those things are converging to say a boxed product launch, would certainly do well, I think, but you’d do an order of magnitude greater, over a period of time, through PC free-to-play.

Tim: Does the truism that you want to create a game that can be played on anything to be successful in the free-to-play market? I mean, Hawken looks and feels like a high-end PC game.

Mark: You know have personally tested the theory. I went out and bought an ultrabook with integrated graphics – basically crappy graphics that can only run DX9. I installed it, ran it, fucked around with all the video settings. You’ll be able to find settings that result in good frame rates and good visual appearance. The thing you’ll be missing will be the anisotropic filtering, the polish basically. But after playing one minute, you don’t miss it.

Our goal was to hit as large a market possible. 70% of the games on Steam would play on our minimum platform.

Believe it or not, even though it does look graphically overwhelming… but it’s not a system killer. This is hard to articulate without getting extremely technical, but I know the Unreal engine inside and out – I’ve produced 13 Unreal games.

When I got to Adhesive the first thing I expected was “this thing looks amazing but it’s never going to run on anything except a super-computer.” Then I opened it up and I’m like “holy shit, you guys pulled every trick in the book that I know. You’re not actually using normal maps on the majority of the objects in the environment. It looks amazing. This looks like a console produced title to me.”

It’s all because of they’re from Project Offset. They all really know what they’re doing.

Tim: The thing that struck me when I first saw it was the density of colour and detail and grime – I guess there’s some very clever tricks in there in terms of keeping the size of the arenas quite small

Mark: It has a sort of a fractal nature. All of that is true, but if you start to deconstruct it… like you study the environment hard, you’ll see, oh, they’re using that mesh in a really clever way, they’ve scaled it all the way up and it doesn’t look like the same thing any more. Pull back and look at the environment and it has that level of complexity. But then if you zoom in and look at the environment it has the same level of complexity. They’re doing some really clever old school tricks… all those little wires and hairs that are on buildings. It’s actually just alpha channelled sprites. You don’t ever get close enough to tell that’s not real 3D geometry.

Tim: It feels like there’s a bit of a gap for a competitive FPS at the moment: the PC’s biggest games aren’t shooters any more.

Mark: Yeah, it’s kind of a return to that Quake era when those games were ascendant. I think it has a lot to do with wanting to get in and have a great experience and then get out. We just have a lot less time for a single game.

We actually play more games, but our expectation is that we’re going to play for a session… I think this was the real genius behind League of Legends… it’s arguably very similar to World of Warcraft, right, but they condensed the experience so instead of a week or a month long grind, it’s a 45 minute session.

Tim: So you’ve been public with Hawken for a while. You’ve gone through what feels like a shortened development cycle. Can you talk about any mistakes that you’ve learned from in that short amount of time?

Mark: Yeah. So the very first one is that Hawken is just graphically complex and it’s also isotropic – it looks the same every way. In early playtesting it was very, very hard to figure out where you were, where you were supposed to go. It was also hard to pull a mech out of the environment.

Another thing was getting the controls right. The team was very used to their own game. The first new players on it had a very hard time with the controls. This is where they really worked their magic where they found a balance between the weight of a mech and the velocity of first person shooters that we’re used to.

After that it was integrating free-to-play, and figuring out how not to gouge players with pay-to-win. That’s not a linear function. You want to be able to level up – not grind too hard, but not make it too easy. Don’t make it too easy for someone to buy their way up a level. There’s a difficult balance: you’re not familiar with the controls, so there’s more reward and less grind. As we began to scale we had to adjust that.

Tim: It’s something you’ll probably have to adjust very quickly when it launche, right?

Mark: Exactly. It’s something that’s lost even on me, coming from a console background. It’s gaming as a service, not as a product.

You have this obligation to improve the title. That’s the monetary exchange here. The guys spend money because you love the title and the reason you love it is because we listen to what you’re saying and we change it and make it that way.

Not only are we reading the forums but there’s deep gameplay analytics that are heatmap based, kill/death ratios, where you opted out, all that will tell us that this Mech is overpowered – this Mech sounds great but it’s really anaemic. The heatmaps in particular helped us design the levels.

If you think about that problem: where it’s hard to work out where to go – we didn’t want to put everything in the HUD – then you’re paying attention to the HUD rather than the world. Instead, we very subtly made texture changes and lighting changes to guide the player to where they’re supposed to do. Those are things we’re going to continue to do – make improvements all the time.

Are you having fun? I mean, this particular moment, it must be incredibly stressful. I see devs at this time in development all the time, and you can just see how stressed they are.

Yeah, it’s usually a complete fucking mess. I’m having a blast, dude. This is the most fun production I’ve ever worked on. You just have this hyper-talented team that needs very little diretction, you have a community that…. you know, when I came back from London [Mark was recently in the UK meeting journalists] I was trying to synthesise what it was that I feel when I talk to journalists…. and the realisation was: “we all discovered this game. It belongs to us, it wasn’t a publisher cramming it down our throats”. There’s a lot of love out there for the title. It just makes you smile.

We’ve had incredible freedom to really do things differently – you know, the first things we showed like the pilot’s head were really out there, not like anything you’d normally see from a boxed product. It’s been a blast.

Tim: That’s the tightrope you walk, right? There’s no-one there to say no.

Mark: And if we’re successful, god knows what will happen, right? Some of my good friends in the industry are the guys that founded Infinity Ward. They were having a blast with those first two titles. Then as soon as they started making a lot of money for everybody they got a lot of help they didn’t ever ask for.

Tim: You’ve talked a bit about a console launch, right? That you’d consider putting in on a console down the line. But all the free-to-play concepts you talked about just can’t work within the current structure of how Xbox Live and PSN work? What has to change?

Mark: They basically have to change their religion, right?

It’s really in the details of how games are certified and launched. You have to pay Microsoft and Sony ten or twenty thousand dollars every single time you want to patch your game. So what happens is that you try and load your patch. You end up waiting and waiting through weeks of pain while the players are telling you “this is crashed and breaking, but you just want to make sure you capture everything.

Tim: Okay – let’s do the inevitable Oculus and VR questions. How hard was it to get the Oculus VR tech working in the game?

Mark: It’s trivial. The Unreal engine is capable of a lot of things that people don’t use it for. It does 3D stereoscopy already right out of the box. Sending it six degree of freedom is something that it can already do – you have complete script control over the camera and that kind of the thing. Getting it integrated is no problem. It’s the tuning that’s the harder problem.

With stereopsis, you’re trying to fool your eyes into thinking that something is 200 metres away when the screen is two inches away. Your pupils are focusing on something two inches away but your eyes are turning inward and outward to focus at that distance.

Fortunately Hawken is just naturally designed for HMDs in that the targets you’re looking at are 100-200 metres away. You tend to have the most problems in corridor shooters where most targets are 1-3 metres away – like you’re looking at your gun that’s right in front of you. It gives people headaches, makes them sick – you have to figure out ways around that.

Tim: Okay – so there’s something that worries me about Hawken. You’re going to be releasing new Mech frames regularly in a similar way to how League of Legends and World of Tanks release new units and tanks. But with mechs, is actually quite difficult to understand why you’d want that mech.

The struggle I think you might have is in defining what their various roles are both in the world, and in the game. Why, for instance, is this Mech worth playing with or buying, essentially.

Mark: I’d agree with that.

Compared to World of Tanks, where you have this intuitive sense of which tank is a better tank because you know what makes a good tank or bad tank.

I think part of what is going to help us communicate that is the environmental changes. You’ve only seen one world level so far. We have five. Some of them are crazy different. There’s a giant forest level, there’s a moon level. There’s a desert level. You’re going to want completely different mechs.

If you think about the Star Wars universe, the vehicles are kind of the same in the second and third films, but they change the design grammar between Hoth and Endor.

Tim: Is there scope for you to be doing vehicles that are not necessarily mechs. That are tanks or speeder bikes… or do you want to keep it purely to two legs, big guns and a cockpit.

Mark: Oh, that’s giving up too much.

Hawken is out now. You should play it. It’s good.